EDITOR, THE ATLANTIC MONTHLY

ONE of the unpremeditated purposes of the Dartmouth Grant is to cool off the President after the rigor and festivities of Commencement. All Dartmouth Presidents are anglers — I assume it is a qualification for the job - but the two I have known should be classified as addicts. I never had the delight of fishing with President Hopkins, though we talked it whenever we met. But John Dickey has taken me up to the Grant for many a June and my love for the place and for the man has increased with each outing.

My anticipation begins to rise with the plane bearing me to West Lebanon, and as we taxi up to the gate of the little airport there is John looming above the waiting passengers with his rusty felt hat on the back of his head. I grin at the other members of the expedition, store my gear in the heavily laden beach wagon with the President's long green canoe strapped to the roof; John takes the wheel and we head north. John gives so much of himself to every Commencement that it is no wonder if he is a little absent at the outset, like a house without its host. But this is the most beautiful drive in New England; we pass through the gleaming white hamlet of Orford, conjecture about the early days in those red brick mansions at Haverhill; catch water vistas such as that of the Connecticut at the Oxbow, and before we have reached the Salmon Pool on the Ammonoosuc John's spirit has returned and the talk is flowing. On one of my early trips Dr. Jay Gile was with us, and his account of the buggy and sleigh rides he had made with his doctor father through these same valleys half a century earlier peopled the road with a romance I have never forgotten.

We drive straight through with only a single stop to buy our licenses and the shadows are lengthening as we make the long run through the Thirteen Mile Woods with the pools and the white water of the Androscoggin showing through the spruce and hemlock. In our thoughts each man is already mounting his rod and trying to decide which fly, wet or dry, to begin with. But first there are two formalities: we make our politesse as we pass through the gate into the Grant. And then when at last we have reached the Management Center to be greeted by Bob Monahan, there is the succulent business of unloading. Mrs. Dickey never quite trusts our ability to net enough fish and so here in case of need are steaks the size of a catcher's mitt, homemade bread, a cherry pie, a tin of cookies, and a crock of fresh stewed rhubarb. Once they have been put in the icebox and the bunks dealt out, the President says in that drawl of his, "Well, I guess we might as well put up our rods and go to work." In his fishing shirt, rusty hat and waders, John is a towering figure; he likes to wade and with his periscope advantage one can understand why. The Half Mile Falls have always challenged him, and after placing his guests on milder waters, this is probably where he will go.

For those who have never seen it the Grant is a forest of 27,000 acres enclosed within the two spreading branches of the Diamond River, the Swift Diamond to the west, the Dead to the north. Eleven miles below Hell's Gate the streams flow together just before entering a roaring precipitous gorge. Along those eleven miles lies the forest which the College has been cutting and cultivating since 1807, an undetermined amount of deer, bear, and varmints, and the wildest trout it has been my privilege to know. By preference we fish the Dead Diamond because it is the more navigable and because in its winding, S-turn course it throws up sandy crescents with delectable pools at either end. The sand bears the footprints of wildlife but never a beer can, bedspring, or the chassis of an old Ford, the normal decoration for so many of our waterways.

Those who have seen it will agree that the Grant is never the same. I have been there when it was so cold that my heavies and the layers of sweaters and windbreak were insufficient and other years when it was so hot that good fishing was confined to dusk and dawn. We fish in pairs, carrying a sandwich (mine always gets wet) and a chocolate bar. These we shove in with a handscoop of riverwater somewhere past the midpoint downstream, often at Slue Gundy, a deep pool still half in shadow at high noon. On one occasion when John and I were working the upper stream and Sid Hayward and Paul Sample the lower, the wind came strong in our face as we approached the Slue. John, wading on ahead of me, put the full power of his right arm back of a dry fly oblivious to the fact that his back cast was already latched to an alder. The shock shivered his middle joint and when I splashed in he had already improvised a splint made firm with adhesive tape and manila strands from the canoe's painter. With this contraption he hooked and was netting another trout, a scene which Paul has preserved in a watercolor.

Faces come out of the past. Sam, the Norwegian fire warden in his conical red hat, never removed, who fed the deer at his door in the dead of winter and who prefaced every one of his Paul Bunyan stories with "Pijesus, I vant to tell you. . . ." Sid with his slow smile. Young John, the most cheerful cook for his years in the north country. John himself working with a hammer and screw driver to free the wedge of hamburg which he had frozen solid in the refrigerator. Dexter Keezer, a master of the wet fly, bringing a sulking big fish to the surface; Dave McCord waxing poetic over a mug of rum; Beth Webster cooking scrambled eggs in the big skillet; George Harrar of the Rockefeller Foundation reflectively wiping the dishes; Ralph Hill, a fellow editor, discussing his plans for the new Dartmouth history, The College on theHill.

And Sinclair Weeks. Sinclair is as staunch a Republican as I am a Democrat, and our trip in the tippiest of all canoes was conducted on a bipartisan policy, that is until we reached the logging bridge which crosses the stream just above the upper farm landing. John was on the bridge awaiting our arrival. I was in the bow in my waders, Sinclair in the stern; the current was stronger than either of us suspected, and as we neared the high bank the canoe began to broach. "You can make it," said Sinny, and I did, with a backward thrust of my left boot strong enough to turn the canoe half over. "Oh, no!" said John who had been taking in the proceedings. "OH, NO!" Sinclair was more explicit. When we had got him back to camp and dried him off, he denied that there were any politics involved, but added, "You'd be a hell of a man on the bridge of the Queen Elizabeth!"

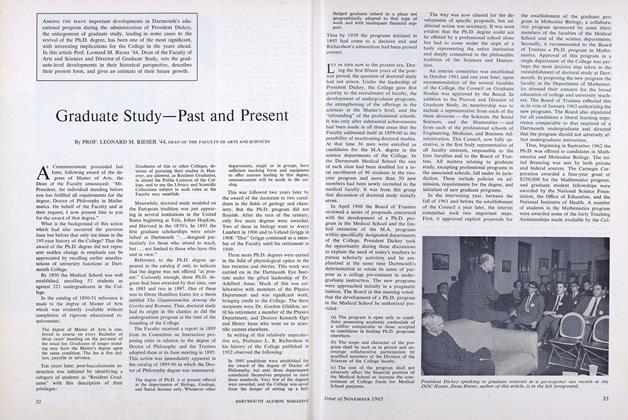

Historically, the high point was President Eisenhower's visit to the Grant in the spring of 1955. He had been visiting Sinclair Weeks in New Hampshire, and after delivering himself of half a dozen speeches, was on his way to spend a fishing weekend at the Parmachanee Club in Maine. John invited him to take lunch at the Grant on his way east and with him came a retinue of Senators, Congressmen, Secret Service men, and reporters. We who were there to fish spent the day before the great event scouring the river for a mess of trout which were to be broiled for the presidential party. That Saturday there wasn't a cloud in the sky and I remember that just after the gatehouse had telephoned to say that the cavalcade was coming in, a golden eagle, which had been nesting on the high cliffs across the valley, swung off and came drifting toward us riding the air currents, so John's greeting was, "Mr. President,, there is an eagle up there which just came out to make you welcome," and as we all looked up, there he was.

As host that day John was perfection. Members of the Outing Club had come to camp to cook a great pit of baked beans and to serve the trout. John presented every one of them individually to the great man, as he did Sam and the other wardens. It was an occasion when dignity and friendliness walked hand in hand.

Late that evening long after the President and his party had moved on, a lumber truck pulled up in the yard and in came a stocky French Canadian reeking with liquor. We will call him Henri Ledur. He had been logging in the Grant and living there in a tar-paper cabin, and when his jags were on him, mistreating his spunky little Indian wife. There and then in ten minutes of downright masculinity, John put him on the carpet, reducing him - temporarily — to repentance and sobriety. That man-to-man talk in the half light was something to have heard; it too is part of the history.

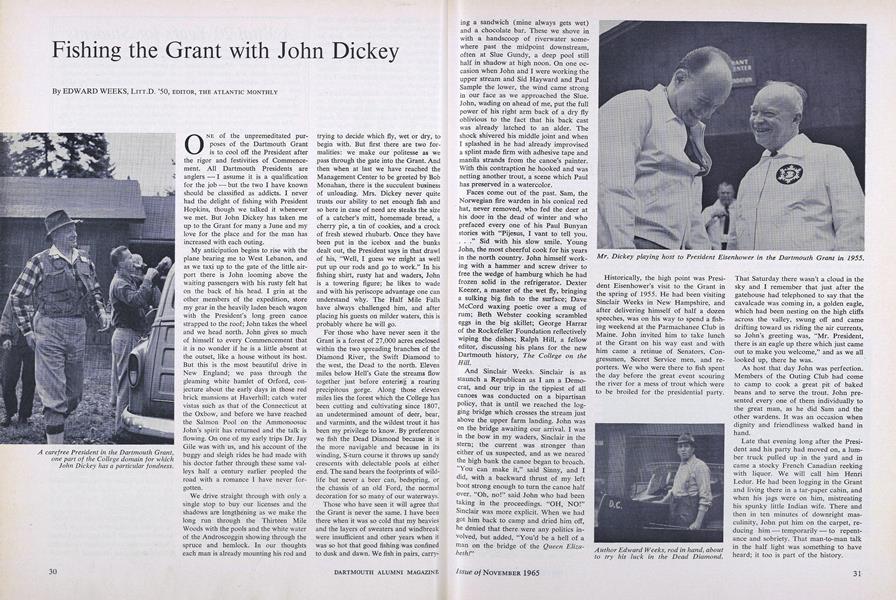

A carefree President in the Dartmouth Grant,one part of the College domain for whichJohn Dickey has a particular fondness.

Mr. Dickey playing host to President Eisenhower in the Dartmouth Grant in 1955.

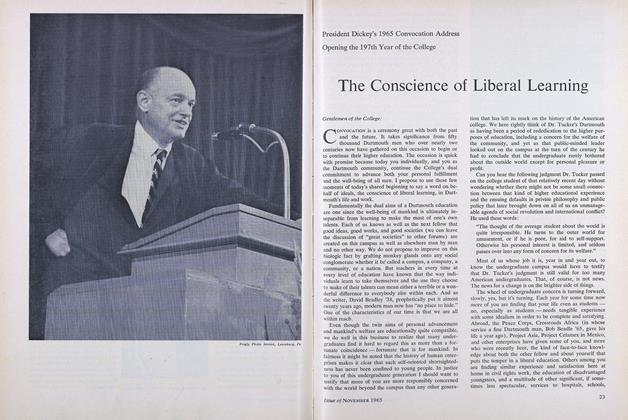

Author Edward Weeks, rod in hand, aboutto try his luck in the Dead Diamond.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGraduate Study—Past and Present

November 1965 By PROF. LEONARD M. RIESER '44, -

Feature

FeatureThe Conscience of Liberal Learning

November 1965 -

Feature

FeatureAn Exciting 20-Year Forward March

November 1965 -

Feature

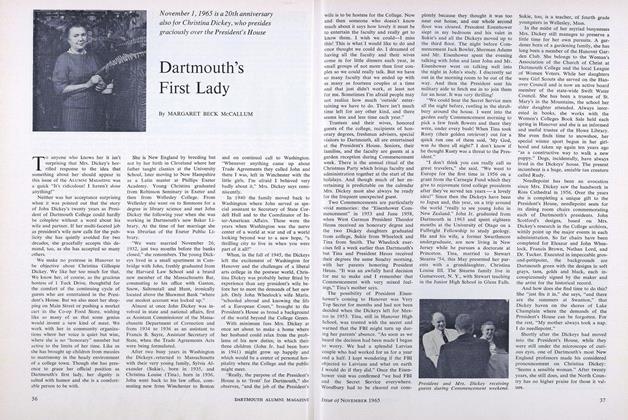

FeatureDartmouth's First Lady

November 1965 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

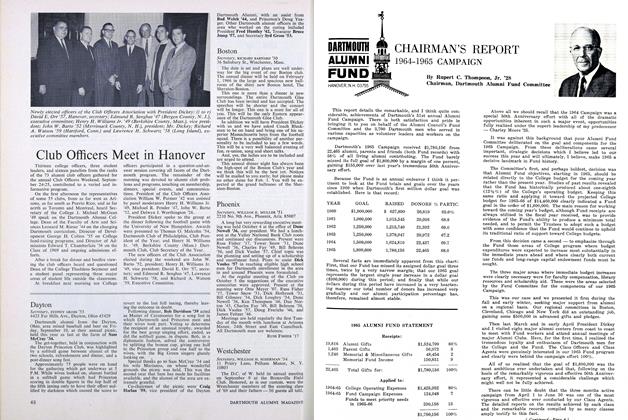

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

November 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28 -

Feature

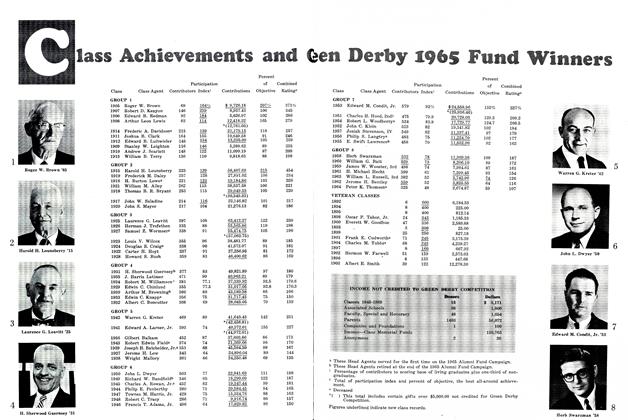

FeatureClass Achievements and Green Derby 1965 Fund Winners

November 1965

Features

-

Feature

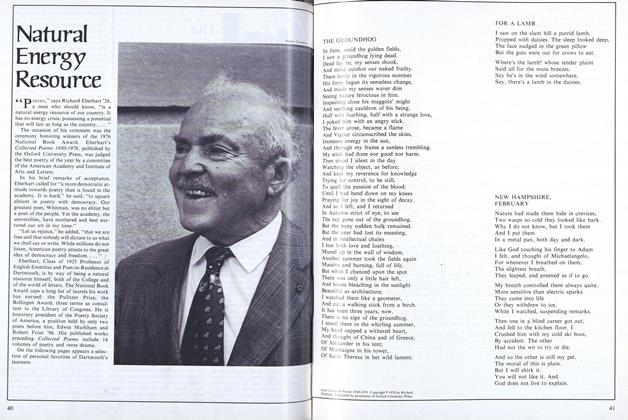

FeatureNatural Energy Resource

May 1977 -

Feature

FeatureCampbell’s Coup

Jan/Feb 2010 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Cover Story

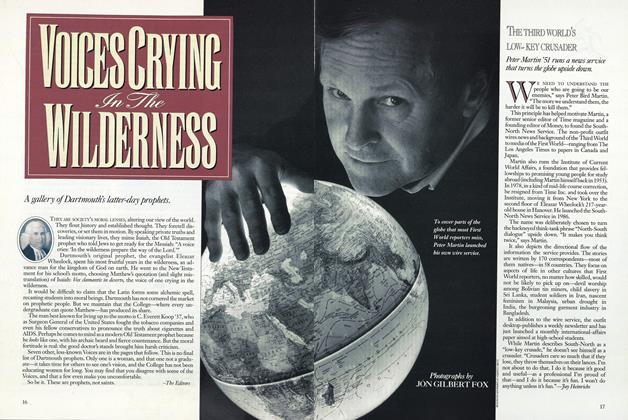

Cover StoryTHE THIRD WORLD'S LOW-KEY CRUSADER

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

COVER STORY

COVER STORY“Take This Advice Today!”

Jan/Feb 2009 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureOne Step at a Time

Sep - Oct By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureSinging Ambassadors

May 1954 By ROBERT K. LEOPOLD '55