Risky Business

As startup mania slows down. Dartmouth dot-commers discover the real meaning of risk.

Mar/Apr 2001 JAMIE HELLER ’89As startup mania slows down. Dartmouth dot-commers discover the real meaning of risk.

Mar/Apr 2001 JAMIE HELLER ’89AS STARTUP MANIA SLOWS DOWN. DARTMOUTH DOT COMMERSDISCOVER THE REAL MEANING OF RISK.

A YEAR AGO, WHEN THIS MAGAZINE FEATURED

successful young alums from Silicon Valley on its cover with the headline "Net Generation," I felt frustrated, downright ignored. A bona fide dot-commer from the Wall Street area since mid-1996, I pouted: "What about Silicon Alley!" Why is there no acknowledgement of us Big Green alums in the New York area? We're pining after that virtual brass ring too, keeping the same killer hours and wearing the same casual clothes that these masters of the Valley are being touted for. Don't we have the same potential for entrepreneurial success?

We certainly did. But there was another potential outcome for all of us Internet entrepreneurs, an outcome other than success, one that does not discriminate between coasts: failure.

Last April, when the "Net Generation" story came out, failure wasn't something seriously contemplated by Internet entrepreneurs on either coast. The smell of success was just too strong, from New York to San Francisco. The Nasdaq Stock Market—the financial goal post for Internet companies—was hitting high after all-time high, reaching 5132 on March 10. Initial public offerings (IPOs) of company stock—the gateway to the Nasdaq—were at record numbers, with both January and February 2000 figures for money raised trouncing 1999 figures.

Unemployment had reached a record 30-year low of 3.9 percent. And staffing was even tighter at so-called New Economy companies, where the constant lure of an ever-newer startup and ever more options made it tough even for relatively established Net companies to retain their brain power. Beyond the markets and the workplace, the mass media saturated us with dot-com ads on buses, on the Super Bowl broadcast, on local radio—even sponsoring high-brow National Public Radio.

By spring 2000, the Internet, once considered an employment backwater for computer nerds and those who couldn't make it in the so-called real world, had become mainstream. Any real risk taker—and don't we all like to style ourselves as such—wouldn't dare sit out this, the greatest, most daring social and business phenomenon of our time.

"On the Internet, anyone has a shot at success," this magazine said in describing the dot-com culture. "Since no one really knows where the Net is headed, nearly any idea is viable. To ignore an idea is to risk missing out on the future."

The risk of missing out. That was the risk that potential dot-commers contemplated back in the spring of 2000. And failure? Back then, failure was having your IPO priced just under the very top of the expected range. Or having to sell your company rather than take it public independently. Or of not being able to grow your company big enough and fast enough. Or of having to accept fewer options at your new job than your headhunter tried to secure for you.

Nearly a year later, alums on both coasts have encountered a new kind of failure: real business failure. The failure of trying to hold together a struggling, suffering company with no hope of profits in sight. The failure of having to lay off your staff. The failure of being among the laid off.

It has been a sobering year for nearly everyone in the dot-com world. A sobering professional experience is not, however, a personal failure. For this article, I spoke with numerous alums in the New York area who've had experiences similar to mine. (I've been an editor at The Street.com, an online financial publication, since its 1996 founding.) These alums, myself included, don't harbor regrets that the wild ride has turned into a Survivor episode. But we do have a more humble, perhaps more mature view of risk than we once did. it's a view that's both informed by our Dartmouth experience and one that perhaps can be of some guidance to current students and alums. And it's a view that might be more appropriate to our times since that April 2000 article, as the economy shows signs of slowdown, and the stock market loses its once relentless momentum.

THE NASDAQ NOSEDIVE

To understand what went wrong with the dot-com economy in 2000, you need to start with the Nasdaq Stock Market. The Nasdaq is an electronic stock market that has attracted most of the small and high-tech firms seeking to become publicly traded companies. Among the stalwart companies that list their stock on the Nasdaq are software giant Microsoft (MSFT), networking outfit Cisco Systems (CSCO), chip maker Intel (INTC) and PC manufacturer Dell (DELL). As Internet and other New Economy companies went public with Nasdaq listings in the last few years, the Nasdaq became a yardstick for the tech/information-driven New Economy.

The Nasdaq has been the holy grail for most Internet entrepreneurs for two reasons. First, by going public—by selling stock in their company to shareholders through the public markets CEOs could raise loads of cash to fund their not-yet-profitable enterprises. Second, as they went public, their own stock in the firm, as well as that of the venture capitalists (VCs) who invested in their businesses, would suddenly become worth scores more than it ever was before. Essentially, once a company went public, the VCs and early entrepreneurs could cash out for big bucks.

The promise of those big bucks fueled a venture capital community that fueled Net entrepreneurs. Any serious decline in the Nasdaq would start a domino effect that would trickle down to these fledgling Net businesses. And that's exactly what happened.

BANKING ON THE MARKET

Tim Bixby '87 saw the phenomenon more closely than perhaps he would have liked. In June 1999, Bixby, a math major at Dartmouth, joined New York-based Live Person as chief financial officer. Bixby had previously worked for giant Universal Music & Video Distribution but was not averse to a riskier enterprise. "Dartmouth forced transitions," he says, referring to the Colleges choppy academic schedule. "We all got more used to change every quarter. I just kept doing that."

Live Person didn't disappoint. The company, which leases software products that enable companies to offer live online customer support and sales services, had just closed on a second round of venture funding when Bixby joined, and it completed a third one soon after. The time was ripe to get started for an IPO—a process that can take upwards of five to six months or more, even on the fastest track.

As it turned out, those months between round three and IPO proved to be precious for aspiring public companies such as Live Person. By early April 2000, when Live Person did go public, the Nasdaq had begun its backtrack. And Live Person felt the effect.

Live Persons IPO "roadshow"—where management touts the potential of its stock to institutional investors—was scheduled during a bleak two weeks for the market. Top Wall Street strategist Abby Joseph Cohen of Goldman Sachs rocked stocks when she said she was no longer recommending an "overweighted" position in technology. A few days later the Nasdaq index fell another 350 points, more than 7 percent. That down day, Bixby and his team were pitching a money manager. "The guy's watching CNBC out of one eye and trying to pay attention to us with the other, and his portfolio was falling 30 percent."

That kind of reception took its toll on Live Person's ultimate public valuation. The stock, originally expected to be valued at between $13 and 15 per share, ended up selling for $8 per share. Even so, Bixby considers the company's timing fortunate, as investors were willing to invest though the company was only showing hundreds of thousands in revenues per quarter. "It was a freakish period of history, and we just sort of hit the right place at the right time." In mid-January the stock was at about $1.

That freakish period for most Internet companies is long gone. The question now is whether companies like Live Person can subsist on the funds they raised until they turn profitable or get acquired. Otherwise, it's essentially game over.

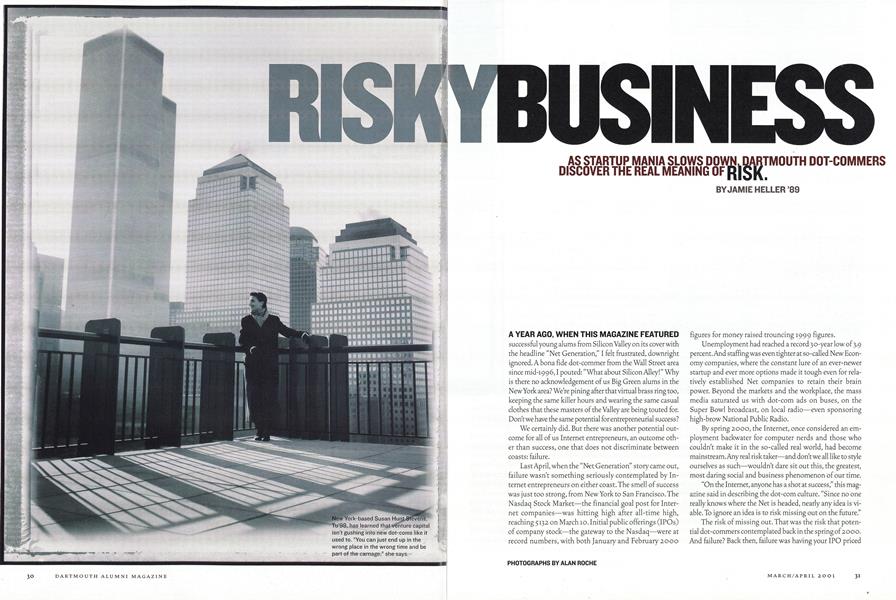

Susan Hunt Stevens, Tu '98, was slated to start raising more venture money for her company, Abridge, in early 2001 as this article was going to press. While confident about her prospects, Stevens, Abridge s co-founder and president, was far from cocky. Abridge, which makes workplace communications software, is not yet public, but Stevens watches the public markets to see how firms in her "space" (business-to-business infrastructure) are faring. She watches because she knows potential investors are doing the same.

The Nasdaq represents investors' best opportunity to cash out. If venture capitalists don't see an eventual payoff for their investment, they won't fund it. And that can mean no more company. "Even if we hit all the milestones that are...laid out," says Stevens, "we're not guaranteed anything. You can just end up in the wrong place in the wrong time and be part of the carnage."

THE ROAD TO RETRENCHMENT

If the Nasdaq had turned around from its initial spring swoon, the dot-com economy might have followed along with it. But instead, the index's downward march accelerated. A steady series of events—from interest rate hikes to oil price spikes to the Middle East crisis to tech stock earnings warnings to the presidential impasse—quashed any bits of momentum the index mustered. After soaring nearly 86 percent in 1999, the index had lost more than 39 percent by the end of 2000.

As the funding manna melted away, Net entrepreneurs had to figure out how to survive on what money they had, even though their business plans generally didn't envision a shorter leash. Despite having popular products, firms such as streaming audio and video company Pseudo.com and law enforcement site APBNews.com were driven to bankruptcy. Others, including my own The Street.com, shuttered entire divisions and implemented company-wide layoffs. At the Tuck School's November eForum—a networking shindig for alums in the Internet industry—an alum of the College cancelled as a speaker at the last minute because he had just laid off 90 percent of his staff, according to eForum organizer Philip Ferneau '84, Tuck professor and program director of Tuck's Foster Center for Private Equity.

In Silicon Alley the New York Post served as the daily chronicler of the slowdown, pasting its business pages with headlines such as "Dot-Corns' Death Dance Getting Faster." New Economy publication The Industry Standard began maintaining a "Layoff Tracker" on its Web site. And Red Herring, one of the venture world's early tech-tilted publications, last January screeched on its cover: "Capital Crisis: Funding Innovation Just Got Even Tougher."

The negative media coverage was not some exaggeration where unrelated incidents were woven into a "trend." Each individual corporate buckle had a real ripple effect throughout the Net community, because during the last few years Net companies largely fed off each other. They advertised on each other. They traded content. They sent each other users. As each one started scaling back or dropping out, it became that much tougher for the remaining ones to trudge forward.

John Fallon '92, COO of Tutor.com, joined that company in February 2000, "when it was all going great," the economics major recalls. But things got harder for Tutor.com, which links potential tutors and students, as they got harder for other Net companies.

In September, for example, Tutor.com licensed a technology from Hear Me, a real-time voice communications company in Mountain View, California. By early December, Hear Me informed Tutor.com it was no longer developing the application server product Tutor.com had licensed, according to Fallon. "It's forcing us to look for other options going forward," he says. (Hear Me later announced a restructuring in which it had "solidified its focus" in its "drive toward a profitable technology licensing business.")

Tutor.com itself hasn't gone unscathed. It laid off eight of its 40 staffers toward year end and continues to monitor its budget carefully. We're "managing down at all times, more so than we were [last] February and March, for sure," says Fallon of the company's budget.

At The Street.com our plans in 2000 shifted from high growth to downsizing within a period of months. I was forced to lay off a group of employees who had delivered a first-rate editorial product on time, because the product didn't have the revenue potential the company had initially—perhaps optimistically—thought it would.

Layoffs were the last thing I'd ever have expected to happen at The Street.com, where I'd spent the prior four years furiously recruiting to build a global news operation. The only people it was worse for than me were the ones who actually lost their jobs—the ones who had shared our faith in The Street.com and the desire to pursue an entrepreneurial adventure. Experiencing layoffs makes you acutely aware of your company's vulnerability, and your own.

WHAT THE FUTURE HOLDS

I could conclude this piece with the typical platitudes: Both the market and the dot-com economy were too frothy. Eliminating the less viable companies and the less viable divisions is a good thing. The return to so-called Old Economy rules is "healthy." And perhaps it is. In fact, I'm sure it is. It'§ the price we pay for living in a capitalist society: Only companies that can make money survive, no matter how cool their Web sites are.

But healthy doesn't mean fun. It is depressing to see projects that you believe in get axed, to see people you admire and care about get laid off, to worry about your own job when the New Economy has already tossed thousands into the employment pool and the overall economy is suffering an increasingly real slowdown of its own.

It's all about the risk side of that risk-reward equation we studied in Rockefeller Center. Risk showed its colors grandly in 2000. And while some dot-commers will certainly reap professional and financial reward in the years ahead, risk has established its place firmly on the ledger.

Maybe it's a generational thing—the dot-com downturn represents the first real rocks we young turks have tripped over in this remarkably bullish decade. Even so, dot-commers have now learned that in an entrepreneurial endeavor, your commitment to the vision of the enterprise had better run deep. Not missing out on the excitement is not the kind of inner motivation that keeps you jazzed when the bad times surface, as they inevitably will.

For Bixby of Live Person, the chance to be part of the senior management team of a young company in a new industry has proven compelling and worthwhile. "I've hit points that I've never thought would be this hard," he says. But, Bixby adds, "to this point I've never thought that I had made a mistake."

For Fallon of Tutor.com, it's providing a service that he cares deeply about—education—to a broad, theoretically limitless, audience. "The most important thing is: Don't get involved in a dotcom just because it's a dot-com," he says. "Technology will change but the market that you serve is what's important." Do something "that you have a passion for."

And Susan Hunt Stevens hits the reward topic that even those who don't focus on can't help but fantasize about: money. "If you were doing this for the money," says Stevens, "you've got a much better bet if you go to Goldman Sachs."

Their message basically comes down to defining success. If professional success is learning something valuable while trying to contribute something new to the world—something you believe is sustainable—then entrepreneurship is a good thing. It's what has motivated me at The Street.com from the start. But those who equate their professional success with corporate stability might be better off at an established investment bank or its equivalent. The institutional track may mean missing out on some excitement on the upside. But it may also reduce the odds of failure—which, as we've all now seen, is a very real possibility indeed.

New York-based Susan Tu'98, has learned that venture capital isn't gushing into new dot-coms like it used to. "You can just end up in the wrong place in the wrong time and be part of the carnage," she says.

When Live Person CFO Tim Bixby '87 joined the software-leasing firm, it was ripe for an IPO. Then the market changed.

John Fallon '92, COO of Tutor.com, knows about layoffs firsthand. "We're managing down at all times," he says.

IT HAS BEEN A SOBERING YEAR FOR NEARLYEVERYONE IN THE DOT-COM WORLD. A SOBERING PROFESSIONALEXPERIENCE IS NOT, HOWEVER, A PERSONAL FAILURE.

ONLY COMPANIES THAT CAN MAKE MONEY SURVIVE,NO MATTER HOW COOL THEIR WEB SITES ARE.IT'S THE PRICE WE PAY FOR LIVING IN A CAPITALIST SOCIETY.

JAMIE Heller is editor-at-large at The Street.com in New York City. Her e-mail address is jamie.heller@thestreet.com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

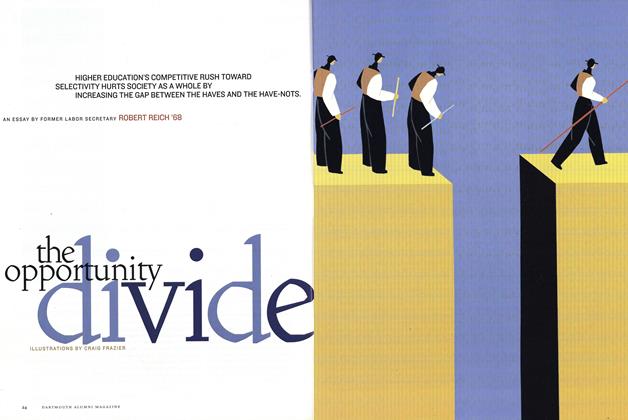

Cover StoryThe Opportunity Divide

March | April 2001 By ROBERT REICH ’68 -

Feature

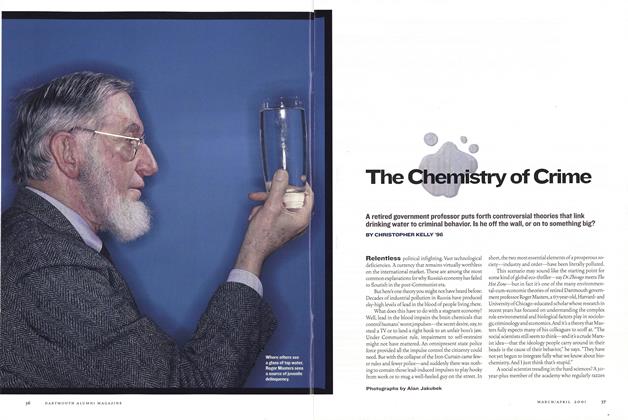

FeatureThe Chemistry of Crime

March | April 2001 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryA Critical Relationship

March | April 2001 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2001 -

Interview

Interview"I Was Made For This"

March | April 2001 By Henry Homeyer '68 -

Article

ArticleNorth Campus Takes Shape

March | April 2001

JAMIE HELLER ’89

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCampus Cosmopolitans

February 1961 -

Feature

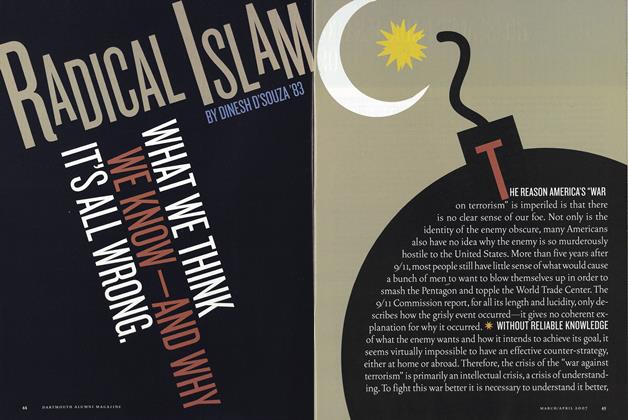

FeatureRadical Islam

Mar/Apr 2007 By DINESH D’SOUZA ’83 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHigher Unhappiness

MARCH 1995 By Frank D. Gilroy '50 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryParadise Regained

MARCH 1995 By Jere Daniell '55 -

COVER STORY

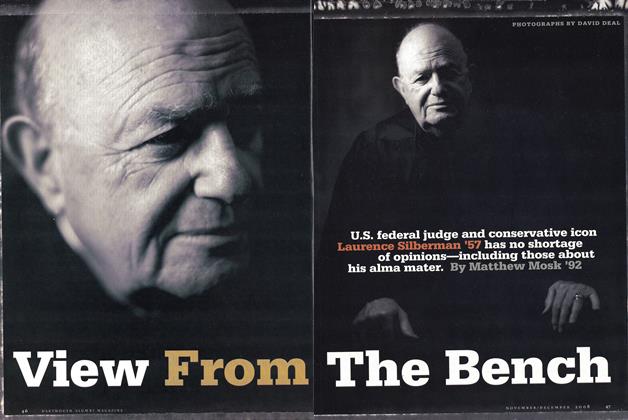

COVER STORYView From the Bench

Nov/Dec 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCox, Poe, and Jefferson's Dead Body

MARCH 1995 By Peter Gilbert '76