An alumna fights chaos in Delhiand wins a good night's sleep.

After graduating from Dartmouth in1985, author Elise Miller spent a year inIndia on a Reynolds Scholarship studyingfreedom of the press. She lived in Delhi withtwo Sikh brothers in a concrete block withbars on the windows and a mat on the floor.As a woman and a Westerner, Miller reports, the complexity of carrying out themost mundane tasks "made a day in Indiafeel like several lifetimes." Now a cook atthe Insight Meditation Society in Massachusetts, she sent us a reminiscent slice ofher chaotic life in India.

MY MISSION of the day was to buy a mattress. I dressed for the expedition in a Punjabi outfit: cotton baggy pants, a smock-like top that came down to my knees, and a broad sash to throw across my shoulders. The Punjabi was a great improvement over the more traditional sari I had worn a week earlier to a Hindu wedding. I'd had to riddle the cloth with pins to escape the kind of insecure feeling that accompanies a strapless prom dress. (If they had known about my sartorial engineering, the Indian women would have been horrified.)

I set out on foot for the central shopping area, Connaught Place—also know as Connaught Circus, which more accurately describes its whirlwind of traffic. To brace myself for this expedition, I first went to my favorite stall for a "mango shake." Seeing me coming, the shake maker began to whip up a concoction of unpasteurized milk, some syrupy-looking liquid and fresh mangos. Frankly, I didn't like to watch the making in progress for fear that I might see some of the all-toointerested flies disappear into the blender. I had determined that it was simply better not to know what I was actually consuming. But the enthusiasm of this man ("Special for you, memsahib," he'd grin) kept me coming back.

Even though we couldn't really communicate verbally, I always felt a special rapport with him. Since I was a regular customer and had bargained for a price the first time I was there, he was willing to forego this ritual. The feeling of being a "regular" was somehow comforting in this vast and overwhelming city—like having your own pub hangout in the middle of London. Sufficiently fortified, I finally arrived at the store where I had been told I could buy a mattress. Going inside was like plunging into Filene's Basement in Boston at Christmas time, except that everyone stopped to stare at me. What was a Westerner doing in a place like this? I had already learned that smiling was likely to get me into trouble by attracting more attention than I wanted. So I tried to pretend that I knew what I was doing.

Stony-faced, I wandered around and around, mesmerized by all the booths and counters. I finally found some mattresses stacked in a corner. Mind you, these weren't Posturepedics but rectangular cushions about an inch or two thick and covered with coarse cotton material. Since I was taller than most Indians, I would probably hang off the ends, but a mattress was a mattress, particularly when a concrete floor was a concrete floor.

A smiling man asked me, "You buy?" I said yes, so he whisked a mattress away and pointed to a woman with a writing pad in her hands. A number of people stood around her while she busily scrawled on pieces of paper and distributed them to the crowd. All I wanted to do was buy a mattress; I didn't want a slip of paper or to stand in line. And I still had to get sheets and a pillow. I was about to explain this to the man, but he had already disappeared, so all I could do was to go over to the woman and wait for a number.

Another customer recognized the anguished look on my face and explained the required procedure in very good English. I had to get this slip of paper so I could go over to the cashier, pay, and then receive another piece of paper which would allow me to pick up my purchases. And I had to follow this procedure for each item I wanted to buy. I thanked him and began my rounds, trying to look less daunted than I felt.

Over an hour later, I finally made it to the line in front of the cashier. The one redeeming factor was that everything here had a set price. It was a government-run store, so I wouldn't have to bargain. When I reached the cashier, the man totaled my purchases and I handed him some cash. He returned one bill to me, saying "No good." He pointed to a slight tear on the edge of the bill. I had been warned about this: Indians won't accept any bills with the smallest of rips in them, and everyone plays the game of trying to pawn off ripped bills on unsuspecting people, particularly Westerners who don't know better. I fumbled for another bill.

I would easily have gotten over the torn bill setback, but when the man handed me my change it wasn't in the form of currency. No bills, no coins, just stamps, like the ones you put on letters. Irritated, I said, "What am I supposed to do with these, mail my mattress home?" He replied, "No change. Stamps." I felt like I was on "Saturday Night Live"—"No Coke. Pepsi." Accept what you get, kid.

Realizing it would be futile to argue, I caught the eye of the friendly employee who had originally helped me with my mattress. He had all of my purchases neatly bundled up and was pointing to the counter where I was supposed to hand in my final receipts. As I started over, he picked up my bundle and headed for the door. "Wait a minute," I yelled. "I'll take that myself." But off he bounded down the crowded street with my mattress slung over his back.

By the time I caught up, he had already flagged down a rickshaw and shoved my purchases inside. The rickshaw driver said, "I take you—ten rupees."

I protested, "Ten rupees? That's ridiculous! I live close by. I'll go by the meter."

"Meter broken," he retorted. "Eight rupees."

I noticed a crowd had formed around the rickshaw and people were watching patiently to see how I would deal with the situation. "The meter's not broken," I said, knowing that was the oldest trick in the book.

"Broken. Six rupees."

"Four," I bargained.

"OK. Five. Let's go."

"Fine," I said (realizing I was now arguing about eight cents in American dollars), and crawled in.

But before we could take off, the man from the store shoved his palm in the rickshaw, demanding a tip for his "help." Exasperated, I handed him a two-rupee note. He looked dejected when we drove off, but a moment later I caught a glimpse of him smiling with his buddies. I guess I'd been had. But at that point I didn't care. I felt the exuberant exhaustion of someone who has just completed a marathon. I had done it. I had met the challenge. I had a mattress.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow I Overcame Lingering Thoughts About The Immorality Of Computers, Edited A Newsletter And Changed My Life In One Week ...

Winter 1987 By Jack Aley '66 -

Feature

FeatureThe Loss of Jacob

Winter 1987 By Peter Dorsen '66 -

Cover Story

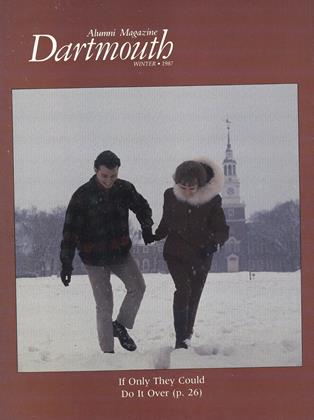

Cover StoryIf I Could Do It Over

Winter 1987 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Feature

Feature5. Residential Life

Winter 1987 -

Feature

Feature4. Men and Women

Winter 1987 -

Feature

Feature2. Drinking

Winter 1987

Features

-

Feature

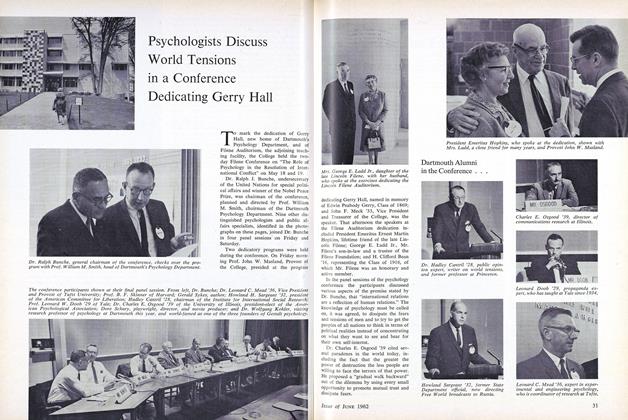

FeaturePsychologists Discuss World Tensions in a Conference Dedicating Gerry Hall

June 1962 -

Feature

FeatureA Mini-Seminar On Two Hood Pieces

MAY 1996 -

Feature

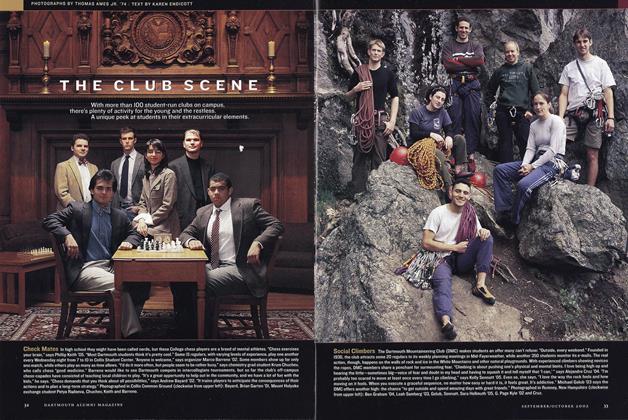

FeatureThe Club Scene

Sept/Oct 2002 -

Cover Story

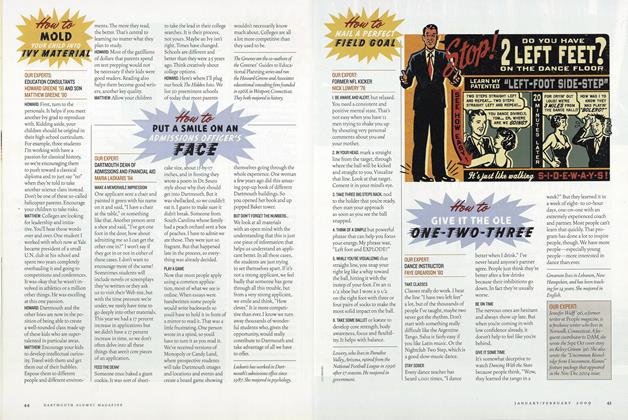

Cover StoryHOW TO GIVE IT THE OLE ONE-TWO-THREE

Jan/Feb 2009 By FAYE GREARSON '80 -

Feature

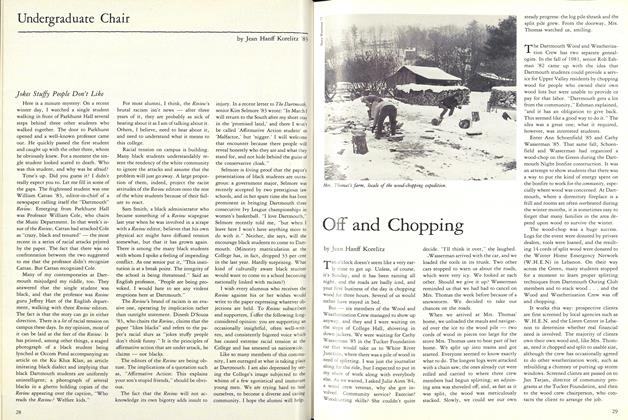

FeatureOff and Chopping

MARCH 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz -

Feature

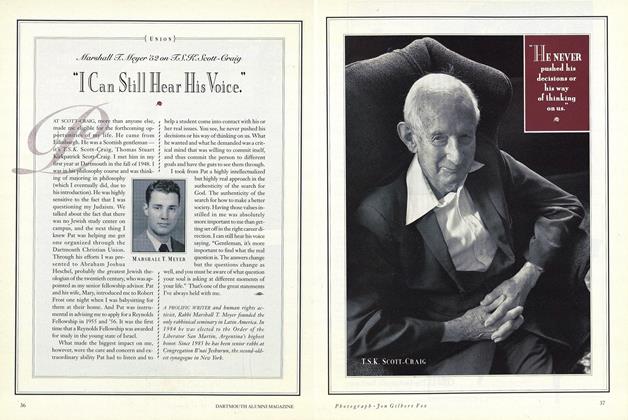

FeatureMarshall T. Meyer '52 on T.S.K. Scott-Craig

NOVEMBER 1991 By T.S.K. Scott-Craig