Fifty years ago, in June 1915, a commencement address, "The Business Man ofthe Future," was delivered by Albert Bradley '15, Phi Beta Kappa student with highesthonors in economics,No. 1 student at theTuck School, and thegraduate voted by theTuck faculty as theman most likely tosucceed in business.The faculty's confidence was wellgrounded - Mr. Bradley went on to become Chairman of theBoard of the General Motors Corporation.Of the address, which follows, Mr. Bradleyrecently told Dean Karl Hill of TuckSchool that it has held up better than someof the things undertaken in his career sincegraduation.

Not so many years ago we thought that the only way to study law was to become a lawyer's office boy; and the only way to study medicine was to become a doctor's body servant, - to be custodian of his horse and instruments. In business, too, we believed the one essential preparation to consist in long experience with the broom.

But modern medicine demands of the young physician a knowledge of facts undreamed of half a century ago. Modern law demands of the young lawyer a knowledge of principles which have developed through legal experience. So, too, modern business demands knowledge of a similarly large body of principles developed through commercial experience, and now in process of formulation. The advent of railroad, steamship, and electrical communication has made possible the development of national and even world markets, has contributed to the growth in size and complexity of the industrial mechanism. We therefore require of the business man greater qualifications than ever before were deemed necessary, so broadened and intensified is the sphere of his actions. And just as modern medicine emphasizes the need for a comprehension of the science of prevention of disease, the most significant phase of its development in recent years, so modern business demands of those who follow its high calling an appreciation that business can and must be conducted in a manner to prevent and not intensify social ills.

To meet such demands requires thorough training before practice.

The foundation of a broad education is needed to promote orderliness in intellectual effort. The college must discipline men to the power to take a large view, and to investigate thoroughly and accurately; to reason logically; to relate fact to fact and principle to principle; to trace effect to cause; to distinguish the essential from the accidental.

But in addition to this general training of the man, changed conditions impose still further requirements on him who follows the career of business. He must have special training for the profession of business. He must acquire a knowledge of changing methods of production; of the source of materials and merchandise; of the mechanism of marketing; of commercial law; of transportation; of commercial geography; of the nature and power and limitations of the corporate form of organization. He must have a knowledge of the primary functions of all business; the securing of capital; the accounting for capital; the organization and administration of materials and men.

These demands represent changed conditions which are evolving a new type of business leader. The former successful business man resembled the captain of an early sailing vessel, who could lash sailors about with tongue or whip, who could accomplish his purpose by feats of physical strength. The newer type of business leader is more like the commander of a modern submarine. He must keep intricate, delicately organized machinery running smoothly, an accident to any part of which may result in disaster to the whole.

Specialization and minute division of labor are the order of the day. The neophyte in a business position is set at a single task, and, shut in by department walls, he has little opportunity to learn broadly either by observation or by experience. If he becomes expert at his task, the more likely is he to be kept at it, unless he has had a training which aids him to comprehend the relation of his task to the tasks of others. Hence the professional school of business must perform for society the function of nourishing and developing individual capacity for organizing and directing, to enable the individual to surmount the limitations that minute division of labor and specialization necessarily impose.

There are at work two opposing sets of forces. On the one hand we have the increasing complexity of modern business, requiring a broad understanding of national and world conditions. On the other hand, we have a keener competition and closer margin of profits, leading to specialization and division of labor for the sake of efficiency in production. To supply a business type that can withstand the crushing of these two opposing millstones is the function of the higher commercial education that supplements the more general college training.

The question arises, Will the introduction of the "bread and butter" motive into higher education tend to lower its ideals? A college must equip young men with a knowledge of the society in which they are to live, a sense of the responsibility which active participation in any part of that life involves; in particular, the relation one's business bears to the whole life of society. The college must so develop moral and social nature that men can never subordinate claims of the higher life of society to their own personal advancement in any material direction. The riddles of this age are economic ones, concerning banking and currency, taxation, regulation of business units, hours and conditions of labor, - business problems — it becomes of vital importance in a government by public opinion that prevailing business ideas should be those that will tell for the greatest advancement of the nation.

How can a university best impress its ideals upon society? Surely not by neglecting the most active departments of social life, but by giving its students every possible assistance in preparing themselves in a large way for the specific careers they expect to follow.

As units of production become larger in size, the proportion of individuals who direct to those who are directed grows smaller, and positions of leadership involve greater responsibilities. As increasing specialization and minute division of labor tend more and more to destroy the individuality of the workman, it becomes increasingly important that some counteracting influence be established, such as giving him some voice in management. Leaders should recognize their positions not as opportunities for exploitation, but as positions of education, leadership, cooperation and trust.

A big problem before the college today is not only to develop in the increasing number of graduates who follow business careers keen minds, staunch characters and intrepid wills, but also to equip them more thoroughly with a breadth of technical knowledge, a comprehension of the relations of the parts of a complex and delicate business mechanism, and an understanding of the basic principles of modern industrial activity. It must convince them that success will be really attained only in proportion as leaders shall regard their positions of private service as offices of public trust.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

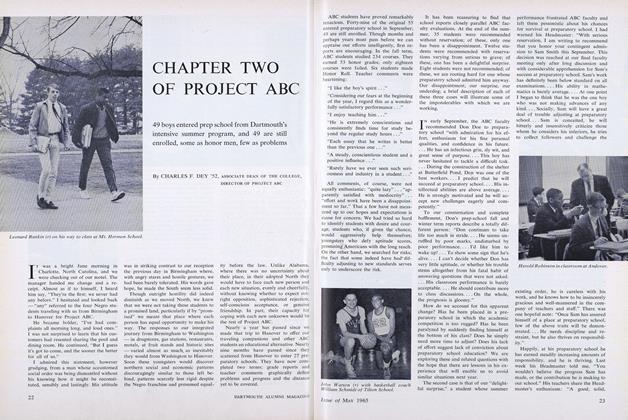

FeatureCHAPTER TWO OF PROJECT ABC

May 1965 By CHARLES F. DEY '52, -

Feature

FeatureWOR's Early Bird

May 1965 By HOWARD L. WEINBERG '62 -

Feature

FeatureALUMNI COLLEGE '65

May 1965 -

Feature

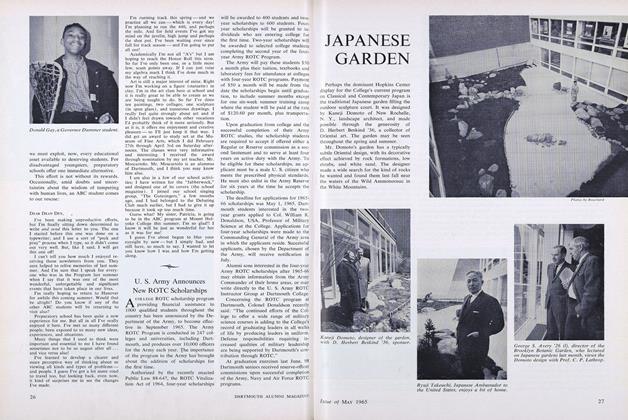

FeatureJAPANESE GARDEN

May 1965 -

Article

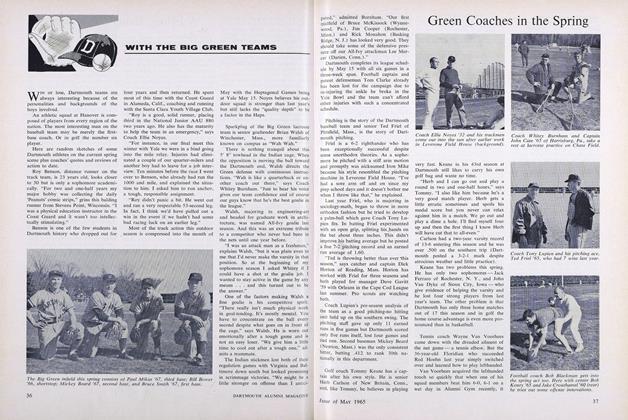

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

May 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

May 1965 By ROBERT W. MACMILLEN, ROBERT H. LAKE