Address by President Hopkins at Bowdoin Anniversary

IN BEHALF OF the historic colleges in representation of which I speak today, I extend congratulations to Bowdoin for her distinguished past and for the limitless possibilities of her future. The increase of years in the life of an institution is not as in the life of an individual, for with years there is available to an institution increasing strength and vitality. It is in recognition that such has been the influence of time upon this historic foundation that I bring the congratulations of her sister institutions.

Moreover, in particular, opportunity such as mine to participate with sons of an associated college as here in their birthday celebration is a privilege to be valued greatly. The relationships between Bowdoin and Dartmouth have always been intimate. From Dartmouth came the first two Bowdoin presidents and from Bowdoin went Nathan Lord to Dartmouth to become third in its presidential succession. If in this reciprocal relationship Dartmouth contributed twice as much in personnel as she received, she on the other hand received twice as much in years of service as she gave. Against President McKeen's term in office of five years and President Appleton's of twelve, President Lord served Dartmouth with distinction for three decades and a half, the longest term of service in Dartmouth's history.

It was this Bowdoin graduate, President Lord, who at a Dartmouth alumni meeting in 1855 gave the most felicitous statement I have ever known why the American college should look to its alumni for support. If in his right as an alumnus he could be here today and should be called upon to answer the rhetorical question to which he replied almost a century ago, I am sure his reply would be the same as then and that he would say, "You ask me to show cause why Bowdoin should continue to have favor of her sons. My answer is a short one,—because Bowdoin is in her sons. There is no Bowdoin without them. They have made her what she is, and they constitute good and sufficient reasons why she should be sustained." So we repeat today.

In our historic foundations of learning the light of the lamp that illumines is also a flame that warms. As a,storm-buffeted traveler on a winter's night may have less sense of chill because of thought of the burning logs of his fireplace at home, so many a former student of colleges such as represented here today finds surcease, whether from heavy cares or petty vexations of a complicated world, by thought of his academic home and his college associations. Not the least of the benefits of a college course is the family relationship bred in the spirit of fellowship among its members. Let those who will scoff at this assertion, it remains a fact. A dehumanized educational process which should strive to transmute into disembodied intellects the adolescent youth enrolled as undergraduates in our historic colleges would contribute little to the understanding of life which the liberal arts college is designed to promote.

"With all thy getting, get understanding," said the prophet, and never was that injunction so greatly needed as in the world of complex motivations and complicated organization of the present day. I have often wished I knew more about how the children of Issachar acquired their attributes, of whom the author of "The Chronicles" asserts, "They were men that had understanding of the times, to know what Israel ought to do." It ought to be fact, however, that in the processes of the American undergraduate college there should be found more instigation to acquire understanding of life as a whole than elsewhere in our institutions of higher learning. This is not to say that the college of liberal arts is superior to all other types of institutions of higher education, but it is to say its existence is indispensable to all others.

In any discussion of institutions of learning it must be recognized that a salutary aspect of the American system of higher education is the fact that it is so diversified. It needs to be. Despite the boasts that optimistically we Americans like to make concerning our unity, we are far from a united people as yet, whether in our antecedents or in our aspirations. Take, for an example, the influence on public affairs of our racial pressure groups. Until late in the last century the stream of immigration into the United States was fronorthwestern Europe and the center of migration to the United States was Amsterdam. Then this center of population moved diagonally southeast across Europe to Budapest accompanying the changes in sources, proportions and nature of the immigration. In the large, those of the earlier groups were highly individualistic and came from countries where government and law stood for protection and freedom. Those of the latter groups were largely gregarious and came from countries in which government and law symbolized to them tyranny and serfdom. As a generalization, it may be said that the earlier immigration distributed itself throughout the country as a whole and predominantly in the rural areas, while the latter tended to remain in urban centers, compact and but slowly absorbed. This change in our population in recent years from a rural to an urban population is something the significance of which is far more important than simply a transfer of country people to the city. There is little understanding among us as yet, however, of just what that significance is to be to our democratic processes. The melting pot has created a blend far superior to anything that we had right to expect so soon but the process is far from complete. For our educational establishment in America, under obligation to offer the opportunities for learning not only to the varied groups of our native population but also to such diverse groups as those of the newer immigrations, varied forms of institutions of higher education not only became needful but were all-important. Fortunately we have the requisite variety in our great tax-supported universities, our technological schools, our church colleges, our junior colleges, our vocational schools, and others.

In contrast to all these stands the independent liberal undergraduate college such as this college is. It is reasonably clear what are the respective interests of the technical school or the professional school, of the junior college or the undergraduate department of the university, and of many another. It is more difficult to define the somewhat intangible purposes of the independent, undergraduate college of liberal arts with its solicitudes for the advancement of cultural standards in our civilization and its absorption in how to establish a reign of gracious living among men.

It should be reiterated, however, that it is in no spirit of derogation of other kinds of institutions that the indispensability of the particular type in which we here today have common interest is emphasized. It is a happy circumstance that the span of Bowdoin's life calls for celebration at this particular time and that attention thus through her should be called to the importance which attaches to the educational thesis of which she in the college world is so eminently representative.

MOTHER OF ALL COLLEGES

It is to be remembered that the independent, privately endowed undergraduate college of liberal arts is the historic college of this country. It is the mother of all other institutions of higher learning which have evolved from the needs of our people. Its interests lie in undertaking to see life in its wholeness and in attempt to comprehend the basis of human thinking and of human action. Its consideration is given primarily to the common denominators which make for fullness of life rather than to exclusive interests which emphasize special phases of human activity. It is characterized as liberal, that is to say, free, because it recognizes no master to limit its right to seek knowledge and it concedes no boundaries to exist beyond which it has not the right to search. Its first concern is not with what men shall do but with what men shall be.

Inevitably thus the objective of the liberal college becomes the stimulation of minds to interest in contemporary problems but always desirably under restraint of lessons of the past and under spur of imagination as to the possibilities of the future. The inert mind may be dismissed at once as futile in itself and useless to all mankind. The active mind which interests itself exclusively in the past has to depend on the written word and produces the pedant. The mind in ferment which looks to the future alone as worthy of attention must remain oblivious to the accumulated wisdom of the ages in experience and is subject to the hazard of a thousand avoidable mistakes as compared with any possibility of having any one idea of worth.

Mankind at large has always had difficulty in understanding its own time but intelligent interpretation has come most largely to generations whose prophets have been seers who have sought comprehension of the present and some vision of the future through viewing events of the past in perspective. Herein lies the vital importance of history and philosophy to the college curriculum. An individual or a generation which is ignorant of its continuity with the past and has no interest in the future is incapacitated for understanding its relationship to the present.

If we turn from ideals of the liberal college to discrepancies between its aspirations and its accomplishments, we may well query, as we contemplate the background of world crisis against which this peaceful event is set, how did the colleges for the last quarter century so largely, if not completely, miss the portents of things to come? Is it not that we have lost the spiritual convictions characteristic of our forefathers who against all difficulties established our colleges in religious faith and nurtured them to strength that men might have access to knowledge and might sharpen vision? Is it not true that these stalwart sons of pioneer stock, strong and independent as they were, still held to the inspiration of belief in a power mightier than themselves wisely to direct the affairs of the universe and avoided the prideful self-sufficiency of recent generations? Is it not true that we, in lack of strong religious faith, have to dangerous extent lost the dynamics of education?

Certainly as a people we have not been free from the deteriorating tendencies and the internal corrosion of something which has overcome all advanced civilizations of the past when at last physical environment has been conquered and necessity for struggle has been largely decreased. Always in the past the beneficiaries of such civilizations have gradually become devoid of sense of responsibility sufficient for cultivating and protecting those qualities the possession of which had previously constituted their greatness. As in the outside world, in our colleges also previous to the war there had begun to appear evidences of the weakening effect of soft living, studied indifference, and cynicism as compared with the combined toughness and humility of mind, the evangelism of spirit and the exaltation of soul in those who originally cleared the land, built the churches, and established educational institutions in our land for the glory of God. Rather than seeking understanding of contemporary life, it had begun to appear that in the demands of a pseudo-intellectualism and in fallacious interpretations of the ideas of freedom and tolerance an instinct was developing in our colleges for avoiding rather than for seeking understanding of life about them. And it was natural that this should be so, for it reflected the spirit of our people as a whole.

Not only was this a demoralizing influence in itself but it gave encouragement for aggression to those plotting against us in their conclusions that our moral defenses were as weak as they conceived our military protection to be. A German propagandist some months ago broadcast to the Reich that there was little to fear from the United States because its people were so intent on waging a comfortable war that they would not allow themselves to accept the conditions of real and widespread self-sacrifice. Consequently, he said, the breakdown of domestic morale under strain and the prevalence of internal dissension would neutralize any contribution that we might make to the war.

WAR HAS SURGICAL ROLE

Fortunately, once aroused—and I am not sure that this is not a debt we owe to the Japanese—we have proved to have the intestinal fortitude to rise to the desperate emergency of the situation. However, the fact that under the drastic surgery of war we have become socially convalescent is no basis for assumption that for past decades we have not been socially ill. In our colleges, as in the population at large, only an occasional voice was raised to emphasize such evident truths as that no people is entitled to more freedom than it is willing to protect and defend; or that security is no sufficient ideal as a challenge to spiritual or moral fervor; or that though men were created free and equal in right to opportunity, they have no equal rights to the rewards of opportunity excepting as they win these; or that "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness" is not the same as "life, liberty and the pursuit of selfindulgence."

To those—of whom there are some—who still resist an invasion of their mental detachment by perturbation of mind and who insist that there is no reason to agitate ourselves in regretful restrospect concerning the past, since America has shown that she can always pull herself together to meet any hazard, reply must be made that we should not forget the narrow margin by which we have escaped adversity and even defeat and subjugation within recent years. Let us remember that only three years ago on August 12, 1941, by only a single vote, 203 to 202, was the bill defeated in the House of Representatives which would have dissolved the small nucleus of an army of six hundred- thousand men which had then been developed and which was to serve as a base for military expansion of the greater army necessary if we should have to enter the war. War was even then imminent and had to be undertaken four months later, after Pearl Harbor. On that same day an amendment was defeated which would have limited the Government to training not more than nine hundred thousand selectees at any one time. Our need has proved to be for more than ten times that number. Whatever one may feel about the judgment of those who cast the minority votes on these matters, however, there can be no question that they represented a large proportion of the public sentiment of that time toward giving any recognition to the realities of the situation.

Moreover, let us consider how largely our own situation today has been assured to us by extraneous events, almost beyond belief, by which we have been saved from tragedy and destruction of all we believe to constitute civilization, such as in the miracle of the British stand after Dunkirk; in the abandonment by the German authorities of the air blitz just as it was about to become successful; in the extraordinary blunder of the Nazi attack upon Russia; in the psychological fallacy of the Axis in its attack upon Pearl Harbor; and in the inexplicable withdrawal of the Japanese forces from Hawaii when she was prostrate and when the Pacific Coast was completely without adequate defenses.

LESSON MUST BE REMEMBERED

No thinking person wishes to dwell needlessly upon the catastrophe that would be upon us and the hazards to which all that we hold dear would be subjected had any one of these results been different, but they should not be ignored and least of all should the lessons to be derived from them be ignored in institutions where it is taught that it is the truth that makes men free.

In summation of the reasons operative to have made us as unmindful as we were of the fate which threatened us and likewise as against the possibility of our subjecting ourselves to like hazards again, it seems to me, moreover, that emphasis in particular should be placed on the fact that a great psychological gulf lies between the philosophy which says that peace must be maintained at all costs and the philosophy which says that war must be avoided at all costs. For those who genuinely love peace with their minds as well as with their emotions there can be no comparison between the validity of the two approaches to the problem of preserving it.

Acknowledgedly understanding of the contemporary scene has been difficult for men of reason in a world where everything has had elements of the preposterous, from the fact that a psychopathic Austrian house painter could be a dominant figure in a threatened overthrow of civilization to the fact that supposedly intelligent men could still argue the possibilities of political and economic isolation for America. Nevertheless,, it has to be conceded that our colleges have not emphasized to the point of persuasion within their own constituencies that no man is entitled to the protection of society to guarantee him "freedom from" anything excepting as he accepts responsibility for protecting that society and for preserving the principle of freedom.

Fortunately the American college is strong enough and its accomplishments are sufficiently great to make its balance sheet convincing as to its worth, despite acknowledgment of grave weaknesses which had begun to appear in its own life in latter years preceding the war. These reflected rather than combated like tendencies in the contemporary social and political life of the civilization to better-ment of which the college had been consecrated at its birth. Heed must be given to the inevitable truth that except as the college utilizes its own freedom, conferred upon it by the material welfare of its maturity, to enhance rather than to depreciate those spiritual qualities upon which emphasis was placed in its foundation, qualities dictated by fortitude, fervor and faith, its superstructure may end in crumbling walls rather than in towering spires.

The historic American college derives from the English and therefore has a tradition of eight centuries upon which to fall back, but in its development it has been sui generis, like the people it serves, and has been characterized alike by elements of strength and weakness such as have been characteristic of this people. Its strength, however, always has outweighed its weaknesses. Restricted oftentimes in the realization of its aspirations by fallacious conceptions of what constitutes a good life, it has nevertheless retained large measure of its idealism in a materialistic world. Attacked persistently as radical when it declared its independence of conventionalists, and denounced as supine when it refused to ally itself with extremists, it has nevertheless remained independent. Operating in recent years between barrages of criticism from within and uncomprehending complaint from without, confidence in it has yet grown and the breadth of its appeal has continuously widened.

Today the major obligation of the college still is to human society, as of old, but to an infinitely widened society on whom except in the Anglo-American world an intellectual blackout has been imposed beyond any possibility of its being lifted for decades to come. For relief from this pall of darkness, so far as relief can be offered, the world must look in the main to America for light. Who, however, thinking of the seedlings from which the flowering plant of higher education in America has grown, can lack faith in regard to determination with which this challenge will be met? In the research laboratories wherein labor the distinguished scientists in our universities and in our great technical schools, amid the abundant resources of our tax-supported institutions, and in the quiet cloisters of our liberal colleges will be heard the call for help to all agencies of higher education,—and the call will be heeded. Physical bodies must be fed and clothed, communities must be rebuilt, the reign of law and order must be re-established upon the earth and the organizations to accomplish these gigantic tasks must be devised. Upon every form of educational institution in this fortunate land providentially sheltered from the ravages of war and still possessed of all its educational facilities will responsibility fall as never before .to prove its worth and to contribute to these ends. Amid all this, what of the liberal college?

COLLEGIATE CONFUSION EXPECTED

It is too much to expect, presumably, that with the best intent there shall not be among fallible men in the educational world as in the political a clamor of tongues and a confusion of cries as to what must be done first and by whom. Perhaps even the demand will arise that the efforts of those who would refine the minds of men, strengthen their hearts, and uplift their souls shall be deferred for a time. If so, let us who have the interests of those gathered here in a learning which creates understanding remember the story of Elijah, jealous for his God, whom the Lord of hosts called forth from the cave in which he had taken refuge and told to go forth and stand upon the mount before the Lord amidst all possible cataclysms of nature. And Elijah waited for God to pass by but he was not in the violent wind, and he was not in the earthquake, and he was not in the raging fire. But it was in a still, small voice that eventually Elijah found the Lord.

So for Bowdoin and for the faith for which she stands today the summons of service can be only in a still, small voice. Even amid the tumult and the shouting we still hear the quiet call to ideals of goodness, beauty and truth. To these our ancient loyalties were pledged. To these our commitments have held through the years. And today the liberal college renews its pledge, consecrates itself anew under God to the upbuilding of a Christian world, and prays for guidance that it may be spared attributes or deeds that would leave its professions ". . . . but as the ghost of friendship dead, A shadow in the glass of faith gone by."

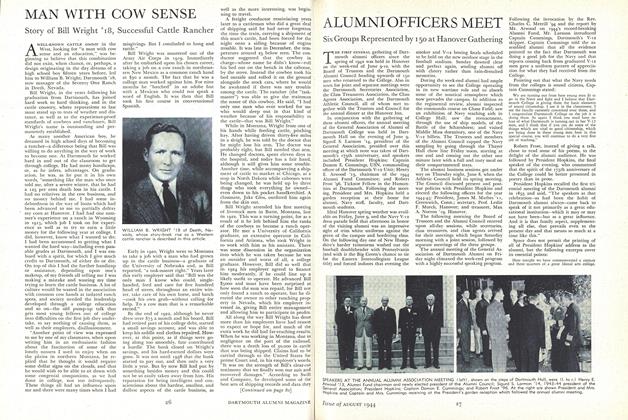

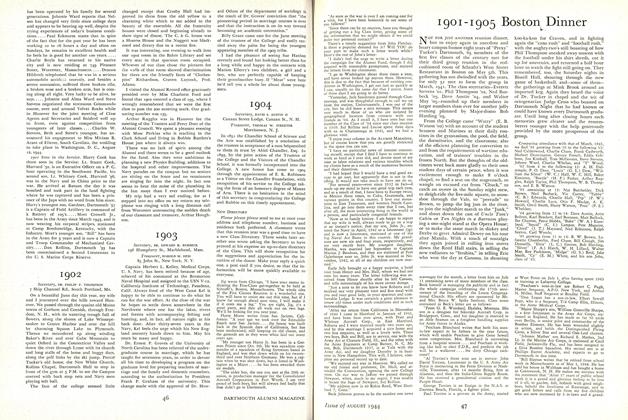

OLD-FASHIONED TRANSPORTATION is used by President Hopkins on his way to the annual alumni meeting in Dartmouth Hall on June 16. Dr; John J. Boardman is the owner-driver.

CAPT. HAROLD HILLMAN '40, USAAC, son of Harry Hillman, track coach, became a prisoner of the Germans when his Liberator bomber, was forced down over Yugoslavia while returning from a raid June 18.

President Hopkins delivered this address, "The Faith of the Historic College," as the Commemoration Address at the Bowdoin Sesquicentennial Exercises on June 24, 1944, at which time he was honored with the Doctor of Laws degree. The MAGAZINE is pleased to be able to print the full text of this especially fine statement about the role of the liberal arts college.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA TEACHING LIBRARY

August 1944 By NORMAN K. ARNOLD -

Article

ArticleALUMNI OFFICERS MEET

August 1944 -

Article

ArticleTHE 50-YEAR MESSAGE

August 1944 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1904

August 1944 By DAVID S. AUSTIN II, THOMAS W. STREETER -

Article

ArticleMAN WITH COW SENSE

August 1944 By A. P. -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Giridled Earth

August 1944 By H. F. W.

Article

-

Article

ArticleEARLY SNOW IN THE CATHEDRAL PINES

January 1916 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS TO MAKE EXTENSIVE ALUMNI TRIP

FEBRUARY, 1928 -

Article

ArticleBarbershopper

May 1954 -

Article

ArticleAgainst Mr. Rockefeller's Plan

JANUARY, 1928 By "F. Clark S. '30." -

Article

ArticleOther Sports

June 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleThe Way to Play

July | August 2014 By GRACE WYLER '09