By John Clark Pratt '54. Garden City,N. V.: Doubleday & Co., Inc., 1962. 400pp. $5.95.

"Where there is much desire to learn," wrote Milton, "there of necessity will be much arguing, much writing, many opinions." I recalled these words as I pondered John Clark's The Meaning of Modern Poetry, a book which intends, admirably, to help the unskilled reader to understand the ways of poetry. It is not the purpose, but the method, which may cause doubts.

The method can be briefly summarized as follows: no two pages of this book can be read consecutively, for each contains some comments about poetry and either asks some questions or answers a question that a previous page has asked. Where there are questions, the reader is given a choice of answers; when he selects one, he is directed to another page, where he will find out if he is right or wrong. If wrong, he is told why and referred back to his starting point to try again; if right, he is told why and sent to some other page for more commentary and questions.

Now all this is ingenious, and perhaps it will help a reader to develop a more sensitive response to poetry; but this reader must admit that the method left his head spinning, as in some mad game of Monopoly. Answering questions and flipping pages, the reader carries on a furious activity in which the game may well obscure the poetry, for after a few paragraphs of commentary, more questions are fired at him, and off he goes again. I suspect that most readers will feel little inclination to pause over difficult material; the questions are waiting to be answered, the game is there to be played, and one is understandably curious to see if he will be permitted to advance or forced to return to Go.

The most obvious danger of the method, both for reader and author, is oversimplification. The reader is asked to choose among answers that are either right or wrong, and he must choose the one right answer that will allow him to continue; where the complexities of poetry demand qualifications and subtle discriminations, or degrees of Tightness and wrongness, the method falters. Suppose the reader disagrees, or feels that he can defend his "wrong" answer? "If you still can't agree," the reader is advised on page 14, "then I suggest that you: (1) Burn the book and go through life thinking poetry is a waste of time. ... (2) Go on to page 12 anyway. ..." Either alternative, it seems to me, indicates that the method has failed, and both seem likely to leave the reader perplexed and frustrated.

A further problem of oversimplification results from the author's having to answer each question in 200 words or less; under such limitations, it is impossible to avoid distortion. The reader is told, for example, that poetry may be divided into two categories, dramatic and lyric. So many objections and qualifications come to mind that one must question the usefulness of the classification, and even the author is hesitant about offering it, for he concludes his discussion of the topic by saying, "Please accept these two terms for the purposes of this book." The method forces the author to ask for such favors, and I am not sure that the reader should be willing to grant them.

Finally I should point out that the title of this book is highly misleading in that "The Meaning of Modern Poetry" contains no poems by Eliot, Pound, Stevens, W. C. Williams, Crane, Lowell, or Eberhart, to name only the most prominent omissions, nor does it discuss the works of these poets. The book includes one poem each by Thomas, Auden, Cummings, Graves, Hardy, Frost, and Yeats.

Department of EnglishUniversity of Massachusetts

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

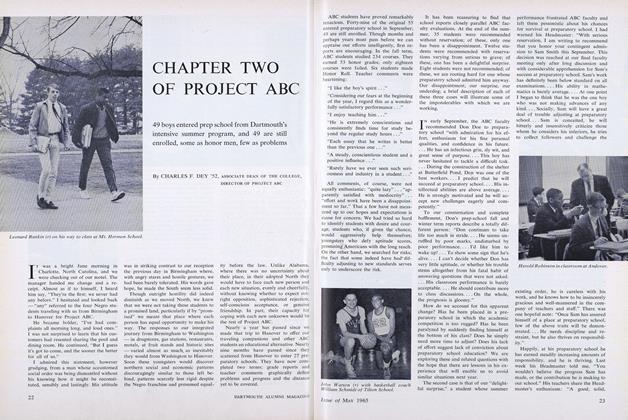

FeatureCHAPTER TWO OF PROJECT ABC

May 1965 By CHARLES F. DEY '52, -

Feature

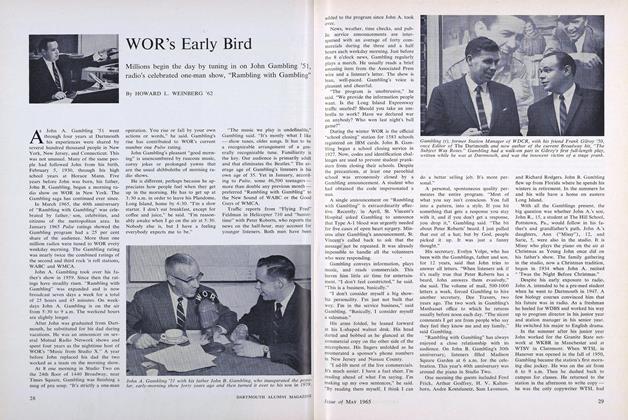

FeatureWOR's Early Bird

May 1965 By HOWARD L. WEINBERG '62 -

Feature

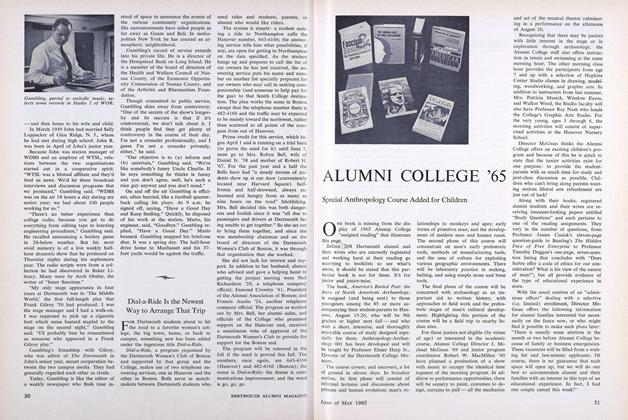

FeatureALUMNI COLLEGE '65

May 1965 -

Feature

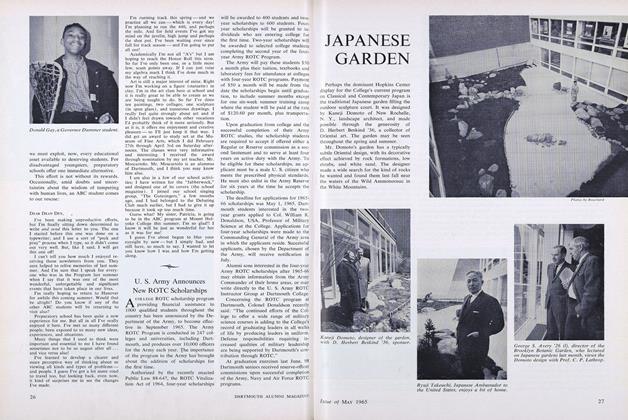

FeatureJAPANESE GARDEN

May 1965 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

May 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

May 1965 By ROBERT W. MACMILLEN, ROBERT H. LAKE

ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56

-

Article

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

January 1956 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Article

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

May 1956 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Books

BooksA YEAR AND A DAY.

OCTOBER 1964 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Books

BooksRICHARD EBERHART: SELECTED POEMS 1930-1965.

DECEMBER 1965 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Books

BooksTHIRTY-TWO DARTMOUTH POEMS. Ed.

MARCH 1966 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Books

BooksWEATHERS AND EDGES.

OCTOBER 1966 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56

Books

-

Books

BooksNew Modern Poets

JUNE 1967 -

Books

BooksTHE FRANTIC PHYSICIAN,OR THREE DRAMS OF MATRIMONIUM,

December 1935 By E. B. Watson '02 -

Books

BooksYANKEE KINGDOM.

July 1960 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksSKIING FUNDAMENTALS, EQUIPMENT, AND ADVANCED TECHNIQUE

February 1937 By Nathaniel L. Goodrich -

Books

BooksGREAT SOUL; THE GROWTH OF GANDHI

July 1949 By Philip Wheelwright -

Books

BooksAppearances Mattered

MAY 1982 By Richard S. Teitz