William Bronk '38. New York: New Directions/San Francisco Review, 1964. 51pp. $3.00 clothbound, $1.25 paperback.

In this second book of William Bronk's poems — his first, Light and Dark, came out in 1956 - the author from first to last admirably sustains the difficult poise that aspires to the creation of philosophic poetry. A writer so motivated probably is deeply concerned with issues of existence that traditionally have been the special province of the philosopher. But he is at the same time a person who by temperament is specially responsive to those qualities of experience that evoke the interest of the artist.

Any such compounding of allegiances exposes the writer to risks from opposite sides. If his philosophy overbalances his art, he produces doctrines interrupted by metrics. If his art overbalances his philosophy, he produces emerald-embellished platitudes. Bronk has avoided both perils. His style suits his matter; and his matter justifies his style.

A. few words first about his style. I spoke of him as a "philosophic" rather than as a "metaphysical" poet in order to avoid the possibility of setting anyone instructed in literary history off on a wrong track. "Metaphysical" might suggest to literary students a convoluted syntax and a sprinkling of elaborately novel images: in short (and rather off-handedly) a junior Donne. On the contrary, Mr. Bronk's syntax is that of soberly considered but quite untechnical speech among educated people. The same comment applies to his diction also. His only conspicuous mannerism is a habit of repeating phrases two or three words long, often punctuated (the practice is perfectly proper) as sentence fragments. His intention usually is to lend emphasis to the phrase, by obliging the reader to pause over it. This device could become monotonous in a book of 300 pages, but retains its effectiveness in the brief compass of this book. As for imagery, he is more than averagely sparing in its use. Seldom does an image remain in the forefront of the reader's visual imagination throughout a poem. Yet on the few occasions when Bronk commits a line or two to an image, he can be exceptionally evocative, as in these four lines ending a poem:

Once in a city blocked and filled, I saw the light lie in the deep chasm of a street, palpable and blue, as though it had drifted in from say, the sea, a purity of space.

To the infrequency of images there is one exception: Bronk repeatedly refers to a shelter, a house, a dwelling of some kind. He does so because this image symbolizes his main philosophic concern. It is nowadays a philosophical commonplace that we manufacture with our own mind and senses the world we see ourselves in. This world is a transcript of whatever is really "out there." The transcript has been acknowledged to be partial, but has been supposed to be reliable, as far as it went. It is characteristic of our century to be unsure about this reliability. Our experience is crossed by intimations of which we are not the origin. Some of them are reassuring; Bronk uses "green" at times as an allusion to these. Sometimes we feel we have been granted more light than usual; but we seldom know what this light has shown us. Bronk's employment of light images suggests this quandary. Frequently, intimations assail us that are disquieting.

In summary, Bronk's poems precisely delineate a major spiritual concern of our time. For this service to his reader, he well merits honor in the college of which he is an alumnus.

Professor of English Emeritus

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStudents and Commitment in the Deep South

June 1965 By BERNARD E. SEGAL '55, -

Feature

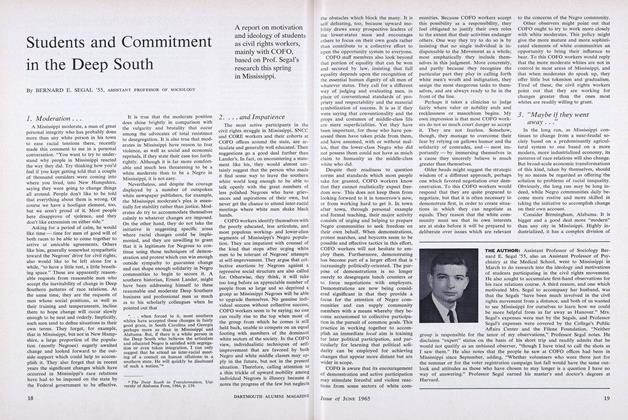

FeatureTHE SUBJECT IS GILROY

June 1965 By RAYMOND BUCK '52 -

Feature

FeatureSocial and Moral Responsibility in the Modern Corporation

June 1965 By RODMAN C. ROCKEFELLER '54 -

Feature

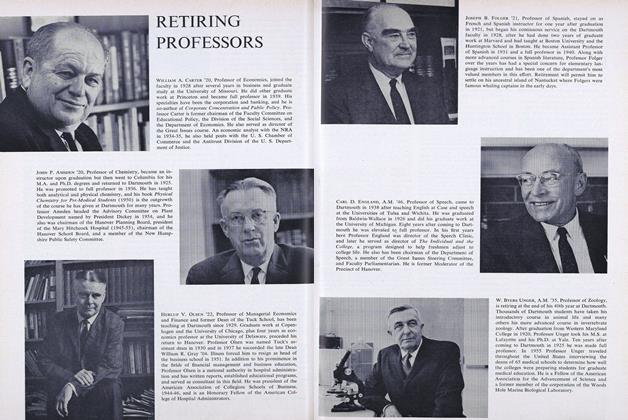

FeatureRETIRING PROFESSORS

June 1965 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65

F. CUDWORTH FLINT

-

Books

BooksBEAU-POIL AU MAROC

June 1940 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksTHE LANGUAGE OF POETRY,

May 1942 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksBROTHERHOOD OF MEN

July 1949 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksSPARROW HAWKS

October 1950 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksSELECTED POEMS

October 1951 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksTHE GEORGIAN REVOLT: RISE AND FALL OF A POETIC IDEAL, 1910-1922.

NOVEMBER 1965 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

April 1941 -

Books

BooksSHAKSPERE, SHAKESPEARE AND

April 1938 By Anton A. Raven. -

Books

BooksTHE SIX LOVES OF "SHAKE-SPEARE."

OCTOBER 1958 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

MAY 1969 By J.H. -

Books

BooksDR. SEUSS'S ABC.

NOVEMBER 1963 By MAUDE D. FRENCH -

Books

BooksDRIFTWOOD: MAINE STORIES.

April 1974 By ROBERT H. Ross '38