THE GEORGIAN REVOLT: RISE AND FALL OF A POETIC IDEAL, 1910-1922.

NOVEMBER 1965 F. CUDWORTH FLINTBy Robert H. Ross '38. Carbondale, Ill.:Southern Illinois University Press, 1965.296 pp. $6.50.

To some literary historians, "Georgian" in its 20th Century application denotes any English literature belonging to the first decade of the reign of George V, from 1910 to 1920. (That monarch reigned until 1936; but the first World War promoted changes that transformed the literary scene.) To others, the term denotes writers, particularly poets, whose work was conspicuous in the five anthologies of Georgian poetry edited by Edward Marsh - the first in 1912, the last in 1922. To non-specialists the term vaguely suggests qualities supposed to characterize the contributors to these anthologies: pastoralism, nostalgia, and tepidity.

In this informative book Professor Ross in earlier chapters employs the first definition. He then somewhat abruptly shifts to the second definition for the ensuing chapters. This strategy enables him to correct several prevalent misapprehensions, notable among them the idea that the qualities indicated by "Georgian" in the third sense noted above summarized the decade as a whole."Quite the contrary! Both the poets and their reflective observers thought of theirs as a time of revived energies attaining new embodiments, in reaction against the flaccidity of such Edwardians as Stephen Phillips and William Watson. This first Georgian decade saw the emergence in or transport to England of such innovations as Futurism, Vorticism, and Imagism. To the proponents of these - Marinetti, Wyndham Lewis, and Pound - Ross devotes considerable attention. Moreover, it was in 1911 that Masefield shocked contemporary sensibilities with what seemed the daring colloquialism and profanity of The Everlasting Mercy. Rupert Brooke, in his Poems of the same year, confronted the British public with such poetic indiscretions as seasickness, which his readers were not accustomed to encountering as a theme for a sonnet.

The fact that Masefield and Brooke were among the contributors to the first GeorgianPoetry volume is evidence that the intention of Marsh was initially to accord a hearing to writers who challenged the conservatism of the public. Indeed, the book came under attack because of what was regarded as the self-conscious brutality of some contributions - notably, Lascelles Abercrombie's "Sale of St. Thomas." Gordon Bottomley's "King Lear's Wife" in the second anthology intensified such objections. Hence it is another misconception to regard "Georgian" in the third sense as a synonym for "Georgian" in the second.

But the intervention of World War I, which destroyed or silenced some poets, the essential conservatism of Marsh in all matters of poetic form and technique, and the withdrawal for one reason or another of notable contributors from participation accelerated the natural tendency of such enterprises to generate and then to become the perquisite of a clique. This tendency was momentarily slowed by the introduction into the third anthology, published in 1917, of younger poets who had emerged in the trenches: Robert Graves, Robert Nichols, Siegfried Sassoon, Isaac Rosenberg. Still, the process was perhaps inevitable; and with the poems of such juniors as J. C. Squire, Edward Shanks, John Freeman, and somewhat superior to these, W. J. Turner - men whom Professor Ross dubs "NeoGeorgian" - the applicability of "Georgian" in the third or pejorative sense became only too apparent. The revolt had fizzled out. Of the men with whom the future of English letters was to lie, only one, D. H. Lawrence, was significantly represented in these anthologies.

All this, Professor Ross has set forth coherently and lucidly. His account raises one cavil: he slights several poets - especially Edward Thomas and Wilfred Owen - who neither initiated movements nor were represented in Marsh's anthologies. That is to say, in this book the shift from "Georgian" in its first sense to "Georgian" in its second comes short of covering the whole territory. Aside from this minor objection, however, Professor Ross competently documents an interesting phase in twentieth-century English literature. He has enjoyed the advantage of access to the papers of the late Edward Marsh (he was knighted in 1937). Hence one finds here numerous details either previously unpublished, or previously unassembled. This book will be specially useful in forestalling the temptation to dismiss Georgian literature with generalizations whose succinctness is merely a cloak for ignorance.

Professor of English Emeritus

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGraduate Study—Past and Present

November 1965 By PROF. LEONARD M. RIESER '44, -

Feature

FeatureThe Conscience of Liberal Learning

November 1965 -

Feature

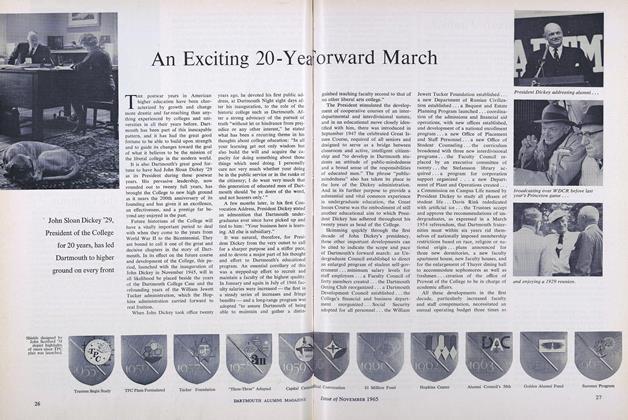

FeatureAn Exciting 20-Year Forward March

November 1965 -

Feature

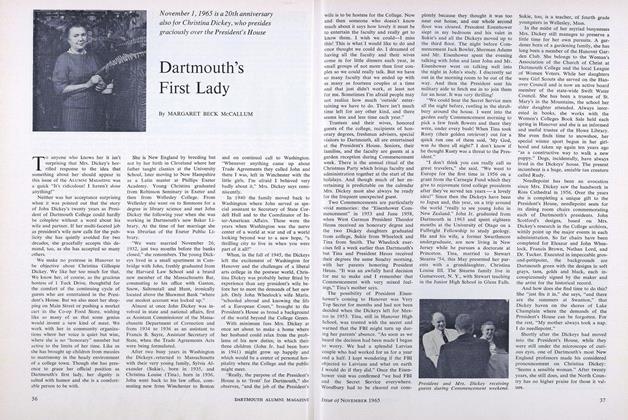

FeatureDartmouth's First Lady

November 1965 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

November 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28 -

Feature

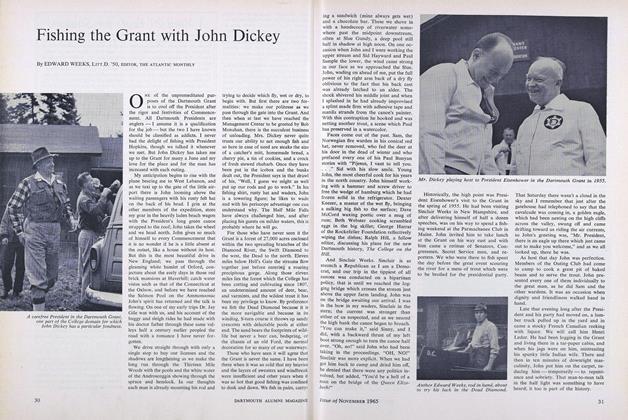

FeatureFishing the Grant with John Dickey

November 1965 By EDWARD WEEKS, LITT.D. '50,

F. CUDWORTH FLINT

-

Books

BooksBROTHERHOOD OF MEN

July 1949 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksSPARROW HAWKS

October 1950 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksAN HERB BASKET,

March 1951 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Books

BooksSELECTED POEMS

October 1951 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Feature

FeatureKenneth Allan Robinson

February 1962 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Books

BooksTHE WORLD, THE WORLDLESS.

JUNE 1965 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Books

BooksShelflife

Jan/Feb 2006 -

Books

Books"GOOD EYES FOR LIFE."

April 1934 By E. H. Carleton, M.D. -

Books

BooksBig Muscle, Big Bucks

December 1980 By James L. Farley '42 -

Books

BooksHow YOU REALLY EARN YOUR LIVING.

October 1952 By L. G. Hines -

Books

BooksTHE FINANCING OF GRANT-AIDED EDUCATION IN ENGLAND AND WALES

June 1940 By Louis P. Benezet '99