MISSION IN TORMENT: AN INTIMATE ACCOUNT OF THE U.S. ROLE IN VIETNAM.

JULY 1965 ERNEST P. YOUNGBy John Mecklin '39. NewYork: Doubleday & Co., Inc., 1965. 318pp. $4.95.

John Mecklin's book, an account of his experience as a member of the American Mission in Saigon during the last years of Ngo Dinh Diem, is a remarkable document. Even in ordinary circumstances, it is rare for a public official to unburden himself so soon after the event. Since Mecklin's subject is Vietnam, his frankness is even more impressive; no one concerned with the questions of peace and war in Southeast Asia can afford to ignore his revelations.

In the spring of 1962, officials responsible for Vietnam felt that something had to be done to improve the deteriorating relations between the American Mission and foreign correspondents in Saigon. Mecklin's appointment as local head of the U.S. Information Service was apparently part of a campaign to correct the situation. He brought to his new job considerable experience as a newspaperman, including a tour in Vietnam during the French debacle and the establishment of the Diem regime. This background has contributed to the striking reportorial detail and depth of his description of American policy and behavior in Vietnam in 1962 and 1963.

In the context of the present debate on Vietnam policy, one of Mecklin's most important points is that, during most of his tenure in Saigon, newspaper dispatches provided a more accurate overall picture of the state of the war than did official American reports. Correspondents in Saigon charged that the American mission was lying to them. Mecklin states that the situation was even more serious: "The root of the problem was the fact that much of what the newsmen took to be lies was exactly what the Mission genuinely believed, and was reporting to Washington. Events were to prove that the Mission itself was unaware of how badly the war was going..." and accepted as fact "material that even an unscrupulous gossip columnist would regard as doubtful." Such revelations (and Mecklin provides much supporting detail) should give pause to those who derive comfort from the belief that the government, with its superior sources of information, is bound to know best in matters of foreign policy.

What were the reasons for this failure of official judgment? Part of the trouble was that the American establishment in Saigon was too much a part of the South Vietnamese government to retain its objectivity. Mecklin describes U.S. operations at that time as a "shadow government," an involvement in South Vietnamese activities to the point where "it amounted to a foreign in filtration of every arm of a sovereign government. ..."

All the while, the prime causes of the South Vietnamese government's difficulties were only being aggravated. "The wrongs that counted in a Vietnamese hamlet were those committed by corrupt local officials, or a greedy landlord. All too often the regime condoned this kind of wrong, while the Viet Cong promised to put it right." Foraging and the use of torture on peasants to get information about the Viet Cong often had the effect of making "the V.C. look like the established authority and the government forces the outlaws. . ." "The unpleasant truth," Mecklin comments, "was that few of us in 1962 (nor two years later for that matter) really had faced up to the depth of our ignorance of the Vietnamese peasant and of the nature of the war in which he was of such pivotal importance."

In his conclusion, Mecklin reduces to three the alternatives now open to the U.S. in Vietnam: negotiation, air attacks on the North, or the commitment of American combat troops in the South. He argues in favor of the third alternative and believes that American soldiers, numbering from 100,000 to 300,000, could establish good government and win the war against the Viet Cong. The South Vietnamese government would be retained, in Mecklin's plan, but would not be permitted to ignore American "advice."

Although he discusses the matter, I do not feel that he satisfactorily shows how an assumption of direct American governmental and military responsibility in South Vietnam, such as he prescribes, would differ substantially from the French effort in the early fifties, nor how it could avoid the same fate. But, whatever disagreements there might be with Mecklin's policy prescriptions, his book remains invaluable for its reporting on the tragic American involvement in Vietnam.

Assistant Professor of History

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Quest for Quality

July 1965 By STEWART LEE UDALL, LL.D. '65 -

Feature

FeatureSidney Chandler Hayward '26

July 1965 -

Feature

FeatureChange and Challenge

July 1965 By HAROLD KING DAVISON '15 -

Feature

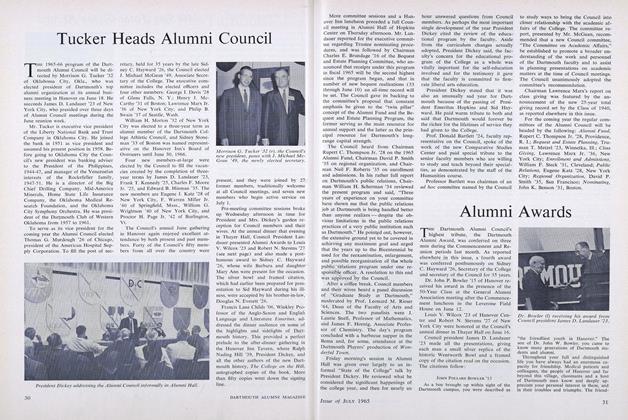

FeatureTucker Heads Alumni Council

July 1965 -

Feature

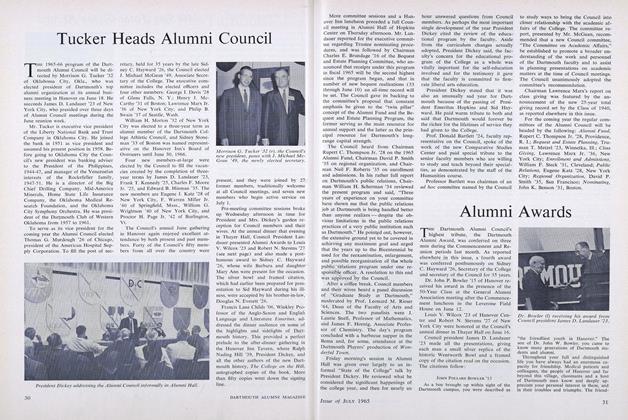

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1965 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1965

Books

-

Books

BooksROBERT FROST THE EARLY YEARS, 1874-1915.

DECEMBER 1966 -

Books

BooksShelflife

Nov/Dec 2004 -

Books

BooksCYCLES: The Science of Prediction

June 1947 By Bruce Knight -

Books

BooksFields of Grace

September 1976 By JOHN HURD'21 -

Books

BooksTHE GREAT POETS AND THE MEANING OF LIFE.

June 1937 By W. K. Stewart -

Books

BooksNEW YORK IN THE CRITICAL PERIOD,

March 1934 By Wayne E. Stevens