by John Moffat Mecklin, Professor of Sociology in Dartmouth College. Harcourt, Brace and Co., New York.

Whether or not there is a revival of religion at the present time, as some people profess to believe, there can at least be little doubt that there is a widespread interest in religion as a topic of discussion or, perhaps, of controversy. The debate over Fundamentalism, the antievolution movement, the publicity given to these and similar matters by the press, are evidence enough. Naturally an outpouring of books upon the subject is taking place. To this current, Professor J. M. Mecklin of the Department of Sociology adds what the present reviewer regards as an important tributary.

Professor Mecklin as a trained theologian, a former professor of philosophy, and a present teacher of sociology, is able to view the subject from many angles. His book is veritably multum in parvo. Within the compass of 250 highly stimulating pages, he discusses the nature of religion, the question of historical criticism, the status of the church in Ataerica, and other problems which his general subject involves. In Chapter I, on "The Challenge of Fundamentalism," it is the sociologist who speaks; in Chapter II on "The Religious Imagination," it is the philosopher; in Chapter III, the biblical critic; and in Chapter IV, all three unite to pool and answer the question "What is Christianity?"

The author's standpoint is best brought out in Chapter 11, which is also the most valuable part of the whole book. One could wish that this chapter were considerably expanded. The imagination is being accorded an increasingly important role in present-day thinking. It is evident that Professor Mecklin has read with profit Vaihinger's "Philosophie des Als Ob" with its doctrine of fictions. He is a philosophical realist, holding that the best theory of the origin of mind is still that which explains it in terms of function and presupposes the conclusions of biology." But imagination, that most intimate, vital and human phase of mind, governs mankind. And it is imagination that produces the rites, symbols and dogmas of religion. These things were originally fictions, in the sense that a work of art is a "make-believe." They represent ideals and aspirations which enable men to live satisfactorily ; but they have no value as literal truth, they throw no light on reality itself. The history of religion is one long record of these imaginative fictions becoming hypotheses and then hardening into dogmas.

Professor Mecklin tells the Fundamentalists that they are effete and that their beliefs have no standing in the intellectual world of today. This is doubtless true, but they have been told those things before and still remain singularly unimpressed. Either they do not believe the statement, or believing it, they solace themselves with the thought that God has chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise. He also deplores the tyranny of religion in American life, telling us, as St. Paul did the Athenians, that we are "somewhat too religious." Yet he finds Protestant Liberalism unsatisfactory in its vagueness, its uncertainty, its persistent pouring of new wine into old bottles without changing the labels. He is more sympathetic towards Catholic Modernism, for it at least respects the continuous tradition of Christian experience, and emphasizes values rather than facts. Modernism, however, was officially condemned nearly 20 years , ago, and exists now (if indeed it exists at all) only sub rosa.

Where then would our author turn to preserve those values of Christianity which ought survive? He does not attempt to answer this question categorically, but is content to pointy out that religion by its very nature has certain necessary limitations (chief of which is absence of exact knowledge), and that it is not to be trusted as a principle of social control. But to religion belongs indefeasibly the realm of ideals and values, where, in the pious imagination, wrongs are righted, failures redeemed, and hopes realized. He says in his Foreword that "this is not the death-knell of faith"; but to conservatives who insist that their religious symbols have objective validity, it will seem periously close to it. It means at least the passing of their type of faith. Many of them will say that their religion is being relegated to Cuckoo-Cloudland.

The book is well written. The sentences are always clear, usually short, and sometimes phrased with epigrammatic skill. The proofreading seems to have been carefully done; the only slips noted are the substitutions of Galileos name for that of Copernicus on page 179, and the mention of Chief Justice Holmes on pages 74 and 100.

The shortcomings of the book are what that word literally implies; there are parts that are too brief, too condensed. There is really material here for two books: one a sociological treatise on current religious movements, the other a psychological study of religion itself. When the two things are combined, as they are here, the unity of the whole is necessarily impaired. This is all the more noticeable, since the tone of the first part is polemical, while that of the philosophic portion is serener and more detached. But such are the penalties one pays for meeting the demands of publishers and of the reading public who want one book, and that a short one. Granted its scope, it is difficult to see how the present work could be much bettered. Certainly the reviewer does not know of another one of the kind that is as good.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSECRETARIES HOLD ANNUAL MEETING IN HANOVER

June 1926 -

Article

ArticleSOMETHING ABOUT BUSINESS

June 1926 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1926 -

Article

ArticleThe new library is assured !

June 1926 -

Article

ArticleTRUSTEES MEET IN HANOVER

June 1926 -

Article

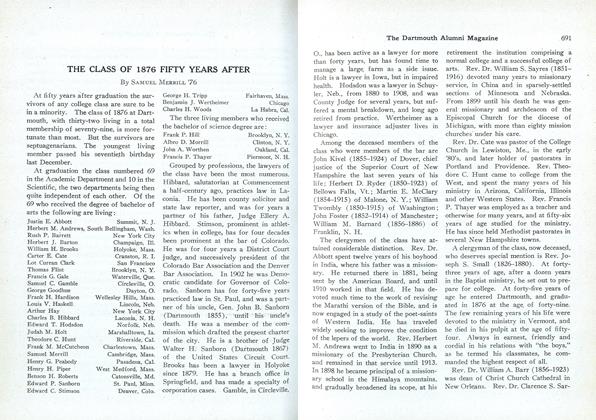

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1876 FIFTY YEARS AFTER

June 1926 By Samuel Merrill '76

William Kilborne Stewart

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

NOVEMBER 1969 -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

January 1920 By c. c. s. -

Books

BooksTHE TRINIDAD CARNIVAL, MANDATE FOR A NATIONAL THEATRE.

APRIL 1972 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksSHEAF OF OATSTRAW.

JUNE 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSCHERZO FROM THE PROUD CITY

June 1933 By L. C. Flint -

Books

BooksICE HOCKEY.

DECEMBER 1958 By TED EMERY