IDEAS, WEALS, AND AMERICAN DIPLOMACY: A HISTORY OF THEIR GROWTH AND INTERACTION.

OCTOBER 1966 HERBERT W. HILLIDEAS, WEALS, AND AMERICAN DIPLOMACY: A HISTORY OF THEIR GROWTH AND INTERACTION. HERBERT W. HILL OCTOBER 1966

ByArthur A. Ekirch Jr. '37. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts,1966. 205 pp.$2.25 (Paper bound).

It may not be altogether fitting to ask one of us to review books by former students. We knew them when they were just starting out, and we have been watching them ever since to see how well they live up to the early promise. The Class of 1937 for some reason has been one especially to watch, and notably Arthur Ekirch, offering us here his seventh book. His record is certainly impressive. Most of his work has dealt with ideas and their place in, and influence on, history (TheIdea of Progress in America, 1944; The Decline of American Liberalism, 1955; Manand Nature in America, 1963; Voices inDissent, 1964), and one has involved both ideas and the formulation of national policy (The Civilian and the Military, 1956). It would be quite natural, therefore, for him to write the present volume dealing with the place of ideas in the shaping of our national foreign policies.

There can be no doubt of the important place ideas have in this area, nor of the persistence with which ideas endure here as elsewhere, often long after the circumstances which once gave them validity have greatly changed. Mr. Ekirch describes the role of a number of ideas, some still valid, some perhaps not, from the first years of our existence as a nation down to the present. It is not possible to appreciate our foreign policies today without knowing how we have been influenced, and still are, by such ideas as those of isolationism, or expansionism, the belief in the special mission of the United States, the desire to create a more democratic and peaceful world.

All these are important. But so too is the belief that the development of national power, the search for power, and the use of power should shape policy, and not much is said about that, nor about the belief that public opinion should shape foreign policies, or the belief in the wisdom of public opinion, which is not always vox dei. Mr. Ekirch is, I am sure, aware of the complexities, but in holding down his book to 200 pages he has at times left things incomplete. The book is, however, a useful introduction to a subject more of us should be familiar with, and the lists of additional readings will be most helpful.

Professor of History

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMILITARY POWER: THE FADING PERSUADER

October 1966 By LIEUTENANT GENERAL JAMES M. GAVIN -

Feature

FeatureWORLD UNDERSTANDING: A Job for Mass Communications

October 1966 By WALTER WANGER '15 -

Feature

FeatureUnderstatement: A Busy Summer

October 1966 -

Feature

FeatureA Landmark Goes Down

October 1966 -

Feature

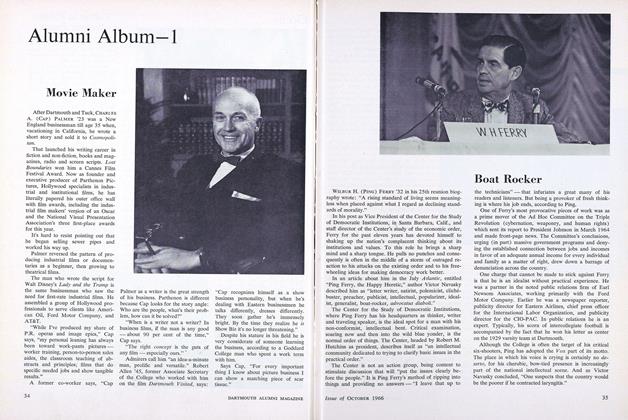

FeatureBoat Rocker

October 1966 -

Feature

FeaturePress Secretary

October 1966

HERBERT W. HILL

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S SKIPPER

June 1944 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Article

ArticleComing: Hanover Holiday 1956

April 1956 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksYANKEE KINGDOM.

July 1960 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksDIPLOMATS IN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION.

FEBRUARY 1963 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksAS A CITY UPON A HILL.

FEBRUARY 1967 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Article

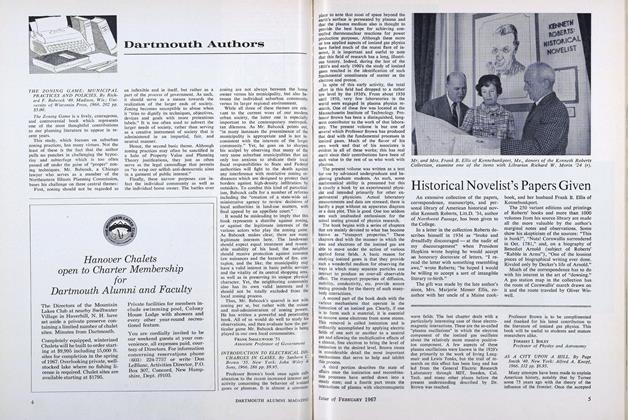

ArticleThose Early Days of Alumni College

MARCH 1971 By HERBERT W. HILL

Books

-

Books

BooksProfessor Gordon Ferrie Hull Jr. '37

February 1946 -

Books

BooksFore

DEC. 1977 By David M. Shribman ’76 -

Books

BooksWHAT THE OLD-TIMER SAID: TO THE FELLER FROM DOWN-COUNTRY AND EVEN TO HIS NEIGHBOR—WHEN HE HAD IT COMING

JULY 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksThe Development of The American Short Story

December, 1923 By K.A.R. -

Books

BooksINTRODUCTION TO BUSINESS

March 1948 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh '11 -

Books

BooksNotes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio

September 1976 By R.H.R.