Among the earliest of the nation's folk figures - one hesitates to call them heroes - are surely that band of dogged, often rapacious loners whom historians have come to call the "mountain men." Engraved on the modern mind's eye by such icons as Frederic Remington's famous bronze, celebrated in the early history of the trans-Mississippi West, the mountain men were the natural stuff of legend even while they still lived.

John Colter, the subject of this biography by the late Burton Harris, was one of the earliest of them. A member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition , he went up the Missouri River in 1804, traversed the Rocky Mountains, saw the Pacific, endured the miserable winter at Fort Clatsop, but chose not to return with the expedition to St. Louis.. Instead, some thousand miles short, he joined two outbound trappers and retraced his steps back into the mountains, where he remained as a trapper, hunter, and explorer for another four unbroken years. When he returned to St. Louis in 1810, he found himself already famous, a part of the growing lore of the mountains.

Subsequent decades did nothing to diminish the Colter legend. Handed down the generations by word of mouth, the Colter stories were told around countless campfires by old trappers to the soldiers and prospectors who formed the succeeding wave of westward migration. They in turn retold the stories to the yet later wave of ranchers and cowboys, who in their turn, as Harris writes, "implanted in their dudewrangler grandchildren a proper respect for Colter's role as discoverer of Yellowstone Park and Colter's Hell." With each retelling, of course, the legend was embellished until Colter had grown to near-heroic proportions. But truth - solid, verifiable fact - was hard to come by.

For unlike some of his contemporaries in the mountains Colter left behind no diaries, no subsequent reminiscences, not even a letter, as far as is known. What few facts about him are ascertainable come only at second-hand, from contemporaries who had talked with him and shared some of his experiences. Thus, a biography of John Colter must necessarily be composed of about one-third fact and two-thirds inference.

Harris's is no exception. In writing it, however, he had a singular advantage over some of the more distant and academically oriented scholars of Western history who had preceded him in studying Colter: Having grown up in the Big Horn Basin, Harris had an intimate working knowledge of the geography and topography of the Colter country. He puts it to excellent use.

It is his first-hand geographical knowledge, for instance, which enables Harris to lend credence to one of the most legendary, if celebrated, feats in Western lore: Colter's incredible exploratory journey of 1807-1808. According to the traditional story, Colter is alleged to have traveled 500 miles alone on foot in the dead of winter; crossed several high, snow- clogged mountain passes; discovered an area of thermal activity in the Big Horn Basin (subsequently dubbed "Colter's Hell" by derisive disbelievers ); discovered Jackson Hole and Yellowstone; traversed the Tetons; and returned to the fort in late spring, 1808.

Harris is one of the believers. "Colter's Hell," he hypothesizes, is a now-dormant area of hot springs, boiling tar pits, and sulphur deposits on the south fork of the Shoshone River. And, he argues - with some help from the Crow Indians who wintered in the area, Colter could probably have crossed into the Wind River valley and walked through Jackson Hole and Yellowstone even at the height of winter.

Colter's life, as Harris concludes, is not without irony. Having survived three near-fatal encounters with Blackfoot war parties, even John Colter had had enough. He came to a sudden decision. "Now, if God will only forgive me this time and let me off I will leave this country day after tomorrow and be damned if I ever come into it again," he is reported to have vowed. He was as good as his word. Leave the mountains he did, on April 22, 1810, and be damned if he ever returned. He went back to St. Louis, married, settled on a small farm a short distance up the Missouri River (quite near the farm, appropriately enough, of the now retired octogenarian Daniel Boone), but died of jaundice in 1813. His final resting place is unmarked , indeed unmarkable. The cemetery in which he was buried was unwittingly excavated and used for fill for a Missouri Pacific railroad bed in 1926. But perhaps it is more fitting, after all, that Colter's memory be perpetuated by no historical marker, but rather by the Colter Legend - as tempered by his most recent biographer Burton Harris.

JOHN COLTERby Burton Harris '27Big Horn, 1977.180 pp. maps. $2.95.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureTwo at the Top: On being a woman, a wife, a partner

October 1979 By Jean Alexander Kemeny -

Feature

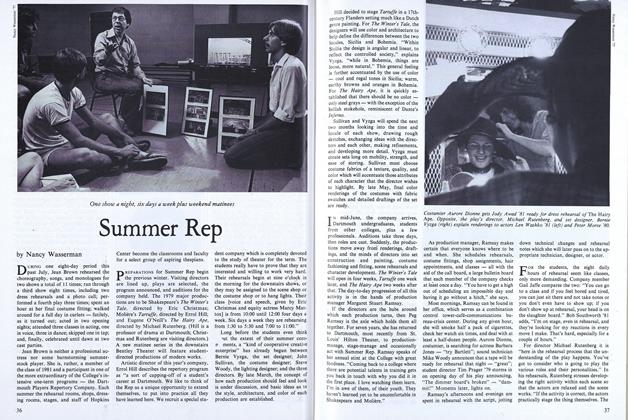

FeatureSummer Rep

October 1979 By Nancy Wasserman -

Article

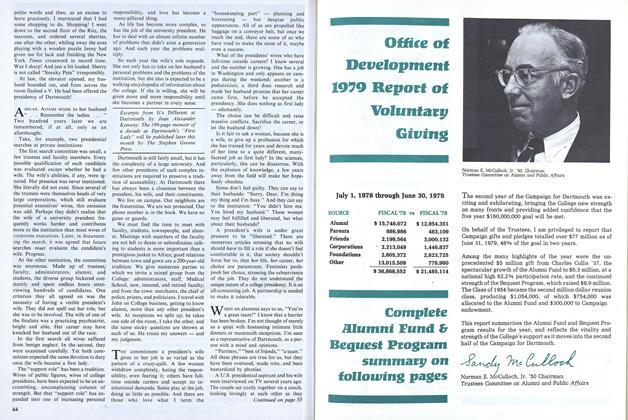

ArticleOffice of Development 1979 Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1979 -

Article

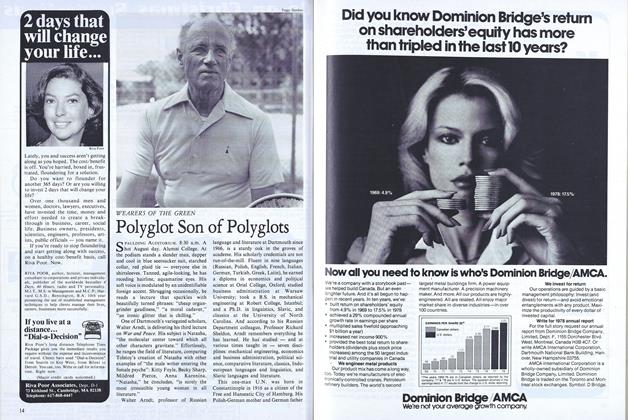

ArticlePolyglot Son of Polyglots

October 1979 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1979 By JEFF IMMELT

ROBERT H. ROSS '38

-

Books

BooksFRANK PEARCE STURM. HIS LIFE, LETTERS, AND COLLECTED WORK.

OCTOBER 1969 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksCredit to the Age

June 1976 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksTelling Tales

APRIL 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksFear of Flying, Combat in the Forecourt

October 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Article

ArticleSteel and Crinoline

May 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksGalaxies

November 1979 By Robert H. Ross '38

Books

-

Books

BooksJohn C. Holme '30

MAY 1930 -

Books

BooksAn Authoritative Obituary for "Well-Roundedness"

June 1962 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Books

BooksREVIEWS OF RECENT PUBLICATIONS BY ALUMNI AND FACULTY TORY TAVERN

August 1942 By Allen R. Foley '20 -

Books

BooksTHESE WERE ACTORS.

January 1956 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Books

BooksGERMIN ACIÓN DEL ALBA.

June 1962 By ELIAS L. RIVERS -

Books

BooksSOME SILENT PLACES STILL.

FEBRUARY 1970 By ELLIS BRIGGS '21