By Carl Bridenbaugh '25. New York: Oxford UniversityPress, 1962. 354 pp. $7.50.

It is hard for us today to appreciate Mr. Bridenbaugh's central theme - that most colonial Americans objected so violently to the creation of an Episcopal bishop for the New World that the proposals to send one over here became a major cause of the Revolution of 1776. We have become so used to bishops of all varieties, so filled with the belief that all religions should be freely exercised, and so far gone along the pathway of religious indifference, that it requires real effort to understand how seriously the eighteenth century felt about all matters touching on their spiritual life and their church. Only on proposals that deal with the relationship between church and state do we even approach the emotional involvement of our ancestors, and while we can perhaps understand their feelings with our intellect, it is hard to do so with our emotions. It was not always possible for even Mr. Bridenbaugh to do that, but it is well worth the time for him to write, and for you to read, this book, because it tells about other things than the causes of the Revolution.

The very tolerance which makes it difficult for us to understand the past is based in part on the same quarrel over a bishop. The Congregationalists, the Presbyterians, the Baptists, and all the rest, were forced to a greater tolerance of each other for mutual strength in the fight against the Episcopalians. They were pushed along this direction also by pressure from the English Dissenters, who worked closely with them and without whose support the struggle would probably have been lost. The cooperation between Dissenting groups on the two sides of the Atlantic shows, incidentally, how close the contacts were, and how each group influenced the other.

The opposition to bishops, starting in the seventeenth century, had time to develop tools of resistance, and in chapter seven is contained their description - perhaps the most useful and novel part of the book. The use of the press, of pamphlets, of sermons could be expected. The rewriting of American history and the creation of the proper historical myths in order to refute the arguments of the Episcopalians perhaps could not be, and yet nearly every age has rewritten the story of its past, and used it for a purpose - and in this case used it very effectively. Even more effective was the machinery created, the church conventions and the committees of correspondence, both taken over by the political opposition to the British government a few years later.

Mr. Bridenbaugh also makes it clear that the rigid stand against the full establishment of the Church of England led to the position that no church should be established but that there should be separation of church and state. They were, therefore, separated in most of the states, and in the Federal constitution, by 1788, and nearly all of us still want them separated.

If the struggle over bishops led many to revolution, it led others to oppose it, and in the religious difference was one of the roots of Toryism. The same struggle had its influence on American higher education, and the pages on Columbia, Princeton, and the University of Pennsylvania are at times diverting. In total, here is a valuable addition to the literature of the American Revolution, to be expected from its author, the current president of the American Historical Association.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePOETRY AT DARTMOUTH

March 1963 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Feature

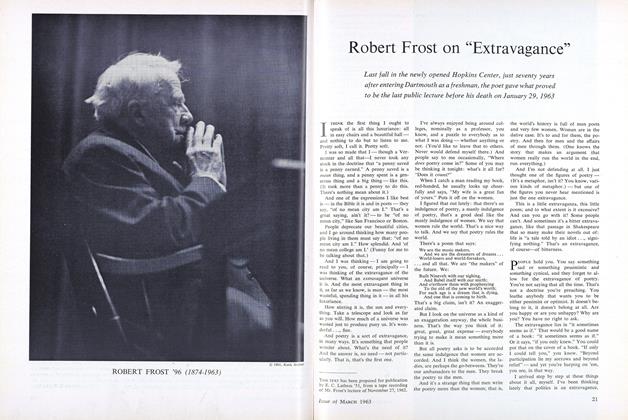

FeatureRobert Frost on "Extravagance"

March 1963 -

Feature

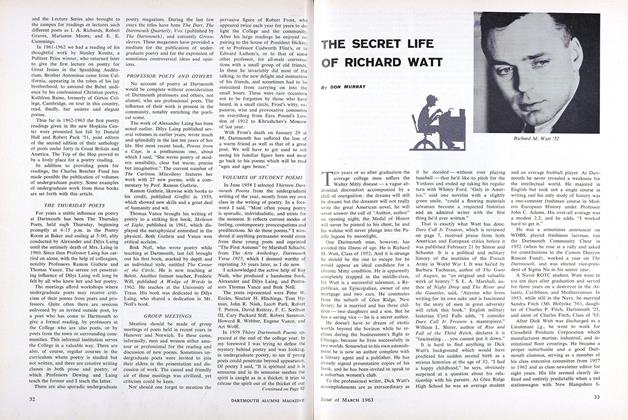

FeatureTHE SECRET LIFE OF RICHARD WATT

March 1963 By DON MURRAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1963 By JOHN HURD, HUGH M. MCKAY -

Article

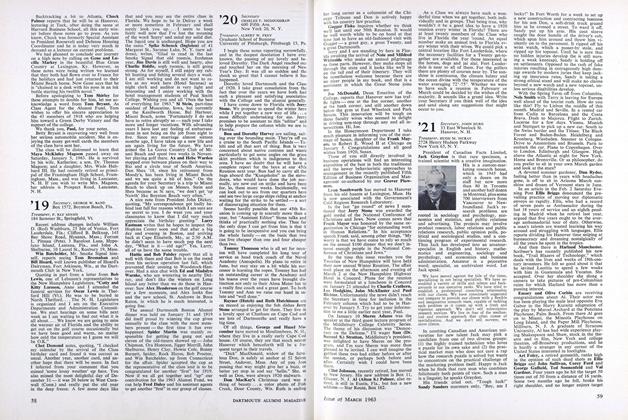

ArticleScholarly Stimulator of Comparative Study

March 1963 By G.O'C. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1963 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY

HERBERT W. HILL

-

Books

BooksREVOLUTIONARY NEW HAMPSHIRE: AN ACCOUNT OF THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL FORCES UNDERLYING THE TRANSITION FROM ROYAL PROVINCE TO AMERICAN COMMONWEALTH

October 1936 By Herbert W. Hill -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S SKIPPER

June 1944 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksKENTUCKY PRIDE.

November 1956 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksTHE EARL OF LOUISIANA.

October 1961 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksDEMOCRACY IN THE CONNECTICUT FRONTIER TOWN OF KENT.

October 1961 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksIDEAS, WEALS, AND AMERICAN DIPLOMACY: A HISTORY OF THEIR GROWTH AND INTERACTION.

OCTOBER 1966 By HERBERT W. HILL

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Notes

October 1948 -

Books

BooksPOEMS FOR A PROSE AGE.

July 1962 -

Books

BooksTHE LOGICAL SYSTEM OF CONTRACT BIDDING

October 1938 By C. H. Forsyth -

Books

BooksECONOMIC PRINCIPLES IN PRACTICE,

May 1942 By G. W. WoodWorth -

Books

BooksAN INTRODUCTION TO THE SOCIAL SCIENCES

October 1941 By Harry L. Purdy -

Books

BooksGEOLOGY OF THE PRESIDENTIAL RANGE

January 1941 By Richard E. Stoiber '32