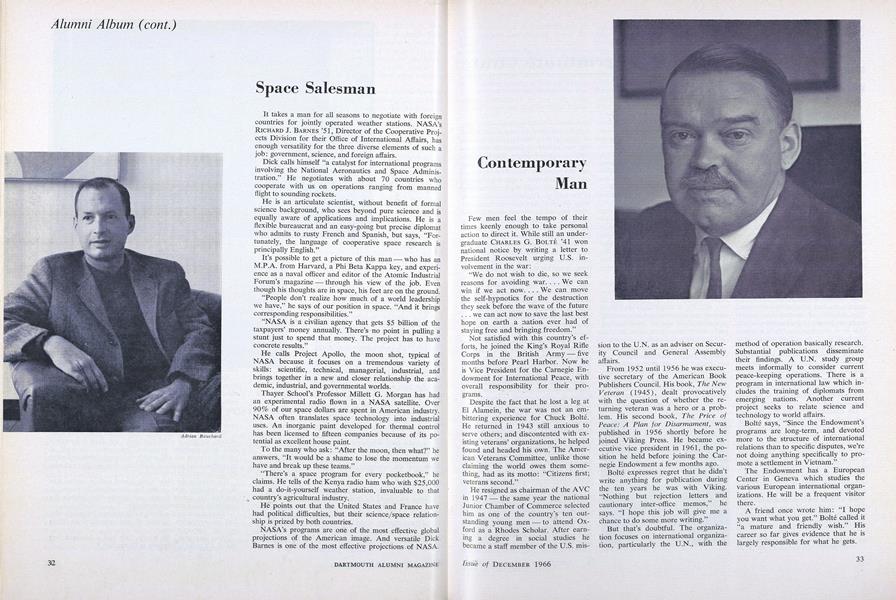

Few men feel the tempo of their times keenly enough to take personal action to direct it. While still an undergraduate CHARLES G. BOLTE '41 won national notice by writing a letter to President Roosevelt urging U.S. involvement in the war:

"We do not wish to die, so we seek reasons for avoiding war. ... We can win if we act now. ... We can move the self-hypnotics for the destruction they seek before the wave of the future ... we can act now to save the last best hope on earth a nation ever had of staying free and bringing freedom."

Not satisfied with this country's efforts, he joined the King's Royal Rifle Corps in the British Army - five months before Pearl Harbor. Now he is Vice President for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, with overall responsibility for their programs.

Despite the fact that he lost a leg at El Alamein, the war was not an embittering experience for Chuck Bolté. He returned in 1943 still anxious to serve others; and discontented with existing veterans; organizations, he helped found and headed his own. The American Veterans Committee, unlike those claiming the world owes them something, had as its motto: "Citizens first; veterans second."

He resigned as chairman of the AVC in 1947 - the same year the national Junior Chamber of Commerce selected him as one of the country's ten outstanding young men - to attend Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. After earning a degree in social studies he became a staff member of the U.S. mission to the U.N. as an adviser on Security Council and General Assembly affairs.

From 1952 until 1956 he was executive secretary of the American Book Publishers Council. His book, The NewVeteran (1945), dealt provocatively with the question of whether the returning veteran was a hero or a problem. His second book, The Price ofPeace: A Plan for Disarmament, was published in 1956 shortly before he joined Viking Press. He became executive vice president in 1961, the position he held before joining the Carnegie Endowment a few months ago.

Bolté expresses regret that he didn't write anything for publication during the ten years he was with Viking. "Nothing but rejection letters and cautionary inter-office memos," he says. "I hope this job will give me a chance to do some more writing."

But that's doubtful. The organization focuses on international organization, particularly the U.N., with the method of operation basically research. Substantial publications disseminate their findings. A U.N. study group meets informally to consider current peace-keeping operations. There is a program in international law which includes the training of diplomats from emerging nations. Another current project seeks to relate science and technology to world affairs.

Bolté says, "Since the Endowment's programs are long-term, and devoted more to the structure of international relations than to specific disputes, we're not doing anything specifically to promote a settlement in Vietnam."

The Endowment has a European Center in Geneva which studies the various European international organizations. He will be a frequent visitor there.

A friend once wrote him: "I hope you want what you get." Bolte called it "a mature and friendly wish." His career so far gives evidence that he is largely responsible for what he gets.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Hoppy" on His Early Dartmouth Years

December 1966 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Philosophy of Culture

December 1966 By ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32 -

Feature

FeatureToro's President

December 1966 -

Feature

FeatureHigh School Principal

December 1966 -

Feature

FeatureSpace Salesman

December 1966 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1966 By ART HAUPT '67

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFaces from the Past

December 1976 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"It Hasn't Been Commercialized"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Cover Story

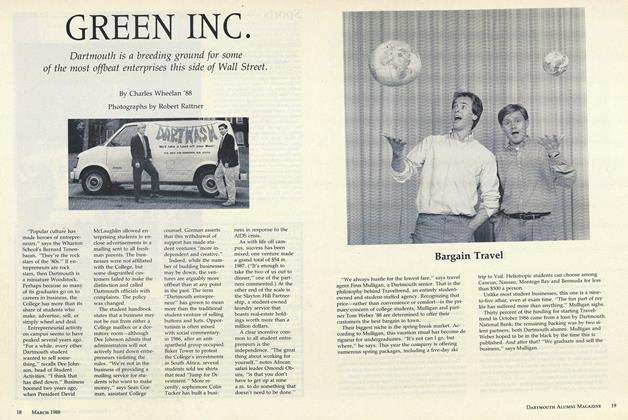

Cover StoryGREEN INC.

MARCH 1988 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

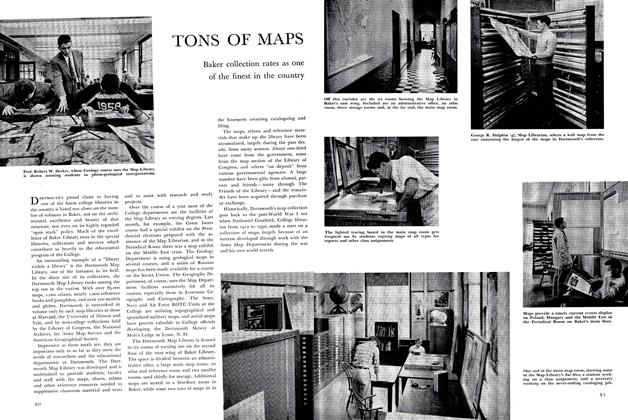

FeatureTONS OF MAPS

December 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureClass Notes

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

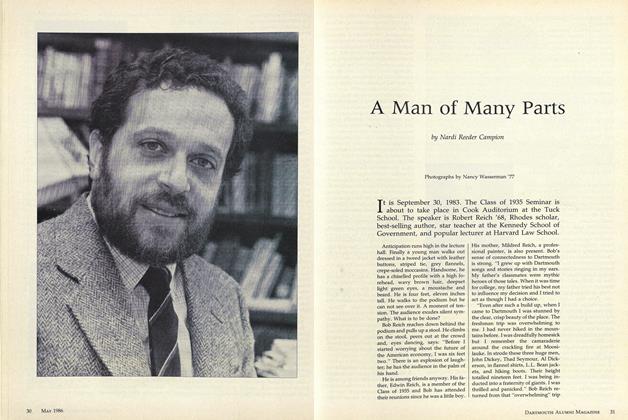

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

MAY 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion