THERE is a curious pattern in the geographic distribution of Dartmouth off-campus educational opportunities. Three winter-term programs explore the tropics, while in other seasons only one, a brief Geology Department foray to Central America, ever crosses the Tropic of Cancer. In other words, an increasing number of Dartmouth students hang up their down parkas and skis, take out their Dartmouth T-shirts, and head south for the long, balmy winter.

When the Trustees sanctioned coeducation and year-round operation in 1971, they implicitly approved more off-campus programs in general. So it is too late to debate the educational benefit of leaving behind for one or more terms an excellent library, computer center, faculty, and dormitory and fraternity friends. Anyway, it makes pretty good sense to study French in France, government in Washington, music in Vienna, and the classics in Greece or Rome. Most of us can think of sybaritic reasons to spend winter in the tropics, but really, why go to Trinidad to study drama? to Mexico to study anthropology, geography, romance literature and sociology? or to Costa Rica and Panama to study ecology? And why go during the winter?

The faculty involved have persuasive answers to these questions and there is another reason, a potential danger in the educational process arising from what might be called a "New England-centric" view of the universe. I am told that some geography textbooks - probably not still in use - were able to link those climates conducive to the maximum human intellectual and cultural development with a latitude roughly corresponding with New Haven, Connecticut. (Some people who have long lived in Hanover might prefer this magical latitude moved slightly northward.) In never leaving New England or the United States one risks a narrow, unrepresentative view of the world. The Earth is not flat. A homebody's perspective is particularly dangerous in light of the increasing impact of the United States upon the rest of the world (Vietnam, the Mid-East) and of it upon the United States (consider petroleum and coffee prices). One's awareness is inevitably expanded by directly experiencing a country very different from one's own, for instance a third-world, tropical country: seeing earthquake damage in Guatemala City, the effects of wild population growth in Mexico City, or jungle life in lowland Costa Rica. A little travel combined with a little inquisitiveness combats this danger of a New England-centric view of the universe. In my own studies I am increasingly impressed with the disproportionately great contributions to their fields of well-traveled naturalists - such as Charles Darwin.

TRINIDAD is a small island in the Caribbean Sea, just off the northeast coast of South America. For most people Trinidad probably elicits an image of little more than steel bands and calypso music. Few would consider it especially notable for its drama, but some time ago I left an interview with Professor Errol Hill, head of the Drama Department, much im- pressed with the scholarship and enthusiasm of this man for this island. (In a sense it is his island; Hill, a tall man of elegant speech, comes from Trinidad.) I was also impressed that Trinidad and neighboring Caribbean islands might just constitute an exceptionally rich setting for the study of drama.

Ethnic minorities ironically are a majority of the people in Trinidad. Large numbers of African, Asian Indian, French (from pre-colonial, slave days), British, and Spanish peoples have deposited their separate influences in the Trinidad cultural conglomerate. These separate influences mesh in the annual pre-Lenten carnival - "the major folk festival of the Western World." Throughout the Dartmouth winter term, from the last of the 12 days of Christmas, celebrated with Old French creche songs, until the carnival, Errol Hill and his students experience the dance, religious ceremonies, songs and music, and folk drama that boil up from the Trinidad cultural stew. This is drama in the broad sense, "culture in being" as Hill describes it.

Freed of European political and cultural rule, today's Caribbean dramatists are asking who are we - physically, linguistically, culturally? By whom and for whom is drama? Local writers and directors no longer just produce European-American imitations. Local themes such as Trinidad's carnival and the search for Caribbean identity play a leading role in contemporary theater. Increased use of "drama" in the broad sense, too, has forced changes in the conception of theater and stage.

These many aspects of drama confront Dartmouth students throughout their encounters with Trinidad and nearby Tobago. Two courses in traditional performing arts of the Caribbean and of the development of its theater since colonial days are taught by Hill. He uses discussion, readings, and lectures, and he has the help of about a dozen local scholars and dramatists, who introduce the students to cultural, political, historical, economic, and theatrical issues.

OUR border with Mexico represents more than just a political boundary. It is a gulf across which loom the Latin American language, culture, and people. Assistant Professor Frank Janney, of the Romance Languages and Literatures Department, describes Mexico today as a "laboratory of naked capitalism, government involvement in social problems, and agricultural transformation - a society in transition." Fully three Dartmouth departments - Romance Languages and Literatures, Geography, and Sociology - have created an interdisciplinary winter program here. The interests are broad and the opportunities for studies are broad. Students "learn Mexico" through living with a Mexican family, contact in class with both faculty and leading Mexican intellectuals, and field work.

Mexico City presents a six-week contact with a large and sophisticated urban center - the oldest in America - with complex history and complex Latin American problems. The variety of local and regional cultures, constituting rich material for anthropological and geographical field studies, reflect the past and rural Mexico. Students spend a week each in Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Yucatan. Literature studies spanning Mexican history infuse the course with another spectrum of culture.

A third group of students winters further south, in Costa Rica and Panama. Here, at about 10° North latitude, Central America narrows and swings eastward into Columbia and South America. It is here that two restless continental areas last mated only a few million years ago and here that temperate North American plants and animals mingle dramatically with tropical South American ones. These are quintessential tropics representing a broad range of rainfall patterns and elevational zones. It is an ecological laboratory for grand evolutionary experiments.

Biologically, the tropics are a quantum leap removed from north-temperate New England. More kinds of birds, for example, may be seen in Costa Rica than in all of North America. More spectacular than this diversity, however, are the adaptations for specialized modes of existence here and the kinds of interactions between different kinds of organisms. Where army ants swarm through undergrowth in lowland rain forests throughout the year, whole assemblages of birds specialize as camp-followers, eating the insects flushed by the ants. Because plant-eating organisms can greatly damage vegetation, especially during a long dry season, certain kinds of acacia plants have evolved systems of defense in which they feed and house stinging ants in exchange for constant guard duty against foliage predators. Such "co. adapted" interactions are virtually unheard of in a temperate forest. Systems for competing with other species, avoiding predators, and for attracting pollinators and seed dispersers often become less believable the more they are studied Troops of howler, spider, and white-faced monkeys abound in almost any lowland forested region of Costa Rica and Panama. Huge trees buttressed to support the weight of myriad orchids, mosses, bromeliads, and vines that can stretch for hundreds of feet stand out way above the forest canopy in the wet forests. A lively zoo and a botanical garden sit right outside the doors of any field station - in fact the zoo does not always wait outside. The tropics contrast maximally with temperate ecological systems and so field work here provides a perspective of obvious value. If a primary raison d'etre of an undergraduate education is novelty of experience, a term spent in Costa Rica or Panama can reward immeasurably.

Other arguments for the importance of studying these regions are more compelling. Tropical studies have contributed in no small way to the major advances characterizing ecological and evolutionary biology in the past two decades, and yet field studies in the tropics lag far behind those in temperate regions. "Temperate biases" that lead to misunderstanding of tropical systems are almost cliches now among ecologists, yet they are innocuous in comparison with attempts to exploit tropical agro-ecosystems, using temperate technology and principles. Disastrous results have overwhelmed large-scale agricultural ventures and will continue to do so because we still only meagerly understand tropical soils, vegetation, climate, biotas, and other ecological factors which determine agricultural success.

This past winter 15 biology students plus faculty and graduate students spent about five weeks in Costa Rica and five weeks in Panama. In Costa Rica they stayed several days in San Jose, and the rest of the time at four field stations , maintained by the Organization for Tropical Studies, a North American-based consortium of universities which maintain field stations primarily for research and graduate education in the natural sciences. The four field stations are as different from each other as can be imagined.

Finca La Selva sits in the Caribbean lowlands to the northeast of a chain of volcanoes that separates the lowlands from San Jose up in the central plateau. The tradewinds deposit massive amounts of water here every month of the year, and the vegetation - both fungus and forest - flourishes. I watched the field station become an instant island last July when the rivers and streams rose exactly 30 feet in just several days.

In northwest Costa Rica the Palo Verde field station looks out over a marsh many miles wide. During the rainy summer it is startling to see desert plants dominating the marsh. For about half the year, however, there is no rainfall, and during this dry period the surrounding hills are leafless and the marsh shrinks into tiny pools where abundant wading and marsh birds and wildlife become concentrated. One learns quickly at Palo Verde to check clothes for scorpions before dressing and to carry mosquito repellent in the field.

Monte Verde is a Quaker colony in the Cordillera de Tilaran to the northwest of San Jose. The epithets "Nirvana" and "Shangri-La" are sometimes used to describe Monte Verde. The people there are exceptionally friendly, speak English, and at least at the Pension Monte Verde serve fresh milk, homemade cheese, and homebaked bread at almost every meal. A nearby national park has preserved extensive tracts of cloud forest where orchids cover the vegetation, resplendent quetzals pluck fruit from the trees, and hordes of North American migrant birds settle down for the "winter."

Cerro de la Muerte is a site of oak forest and "paramo" - above-treeline, Andean-derived vegetation - at about 10,000 feet in the Cordillera de Talamanca between San Jose and Panama. Frost appears almost daily throughout the year on the highest mountains, and the plant and animal life is quite temperate in character, although such tropical groups as hummingbirds and bamboo plants are .very conspicuous. Abundant cloud cover and wind require warm clothing and have no doubt contributed to the name "mountain of death" for this place.

In Panama the biology contingent resides at the Smithsonian Institution field station on Barro Colorado Island in the Canal Zone. From this island and its comfortable field station in the lowland wet forest, students visit the island preserve, the adjacent mainland, the coast (for such marine habitats as coral reefs), and more distant sites in the Chiriqui highlands in western Panama.

All of these sites in Costa Rica and Panama, as well as the field locations in Trinidad and Mexico, unveil for the student a new domain for exploration. Field work in Mexico is intensive and, as Professor Janney describes the experience, designed to "stretch students to capacity" in dealing with their new surroundings. There is an opportunity in these tropical laboratories for a kind of creativity in research rarely available back in Hanover. A day in Costa Rica or Panama is fully spent: breakfast at six, often following brief forays to set up equipment or make dawn observations. Organized "field problems" in the morning yield to data analysis or keying of organisms in the afternoon, followed later by lectures in the afternoon and evening. After acquiring field experience, students spend more time later in the term on independent projects. Students in these programs experience more than just tropical biology or Trinidad drama. The process of working under cramped, adverse conditions is itself an experience for many students, as is the process of working closely in the field with faculty. Professor Richard Holmes, who launched the Biology Department program, describes this latter benefit: "A full time, in-depth experience of studying biological processes in their natural setting, in close combination with faculty members, will provide a depth of understanding and involvement for students impossible during a term on campus."

Skeptics might wonder how these tropical extravaganzas are financed. In most cases they cost participants little more than a term on campus. In the Trinidad program students pay for transportation and normal tuition, but save on room and board. The Drama Department supports local speakers and the costs of events indispensable to drama studies. Staying at field stations in Costa Rica and Panama is expensive - $20 a day in some places - but overall students pay about the same for room, board and tuition as they would on campus in addition to paying for transportation to and from the tropics. The costs of using field stations would be higher without Dartmouth membership in the Organization of Tropical Studies, which was generously underwritten this year by Robert Dorion '47, who is interested in tropical studies in Guatemala where he resides.

Some people may label such off-campus programs frivolous, and to some students these opportunities hold little appeal. I cannot help waxing enthusiastic about them when I consider their importance to my own education. For one thing, travel provides new perspective on one's sense of place. For many people who have passed through Dartmouth, New England is a very special place. I wonder, however, who can truly love New England who has not left it for a while. After spending many years there myself, I am even fond of New England winters.

Thomas Sherry '73 is studying for an advanced degree in biology at UCLA. He hasalso written about New England squaredancing for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1977 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureMr. Hopkins Builds a Library

April 1977 By CHARLES E. WIDMAyER -

Feature

FeatureThe Road Not Taken

April 1977 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Article

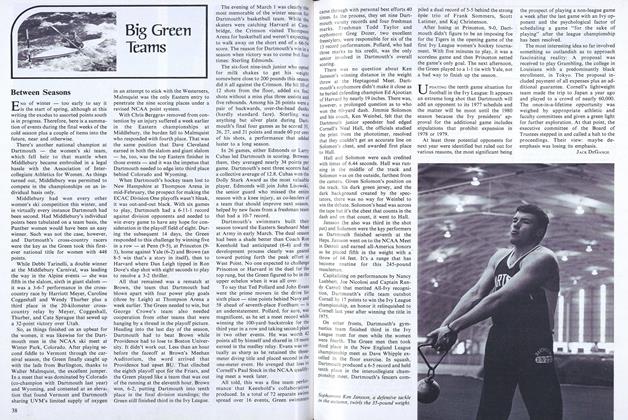

ArticleBetween Seasons

April 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleTopeka Takes On the Hun

April 1977 By NICK SANDOE '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

April 1977 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., LOUIS N. PERRY

Features

-

Feature

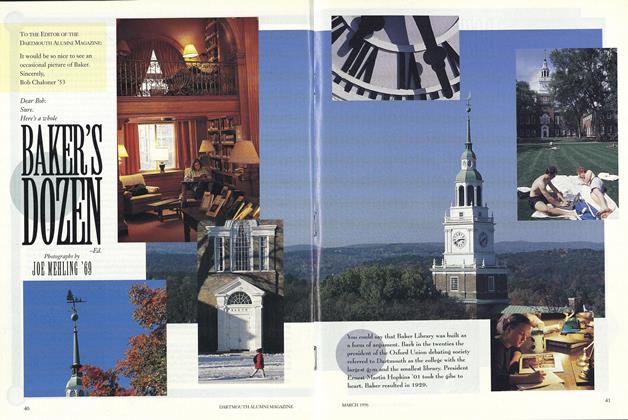

FeatureBAKER'S DOZEN

March 1996 -

FEATURES

FEATURESSian Beilock

MAY | JUNE 2023 By ABIGAIL JONES '03 -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

October 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryParadise Regained

MARCH 1995 By Jere Daniell '55 -

Feature

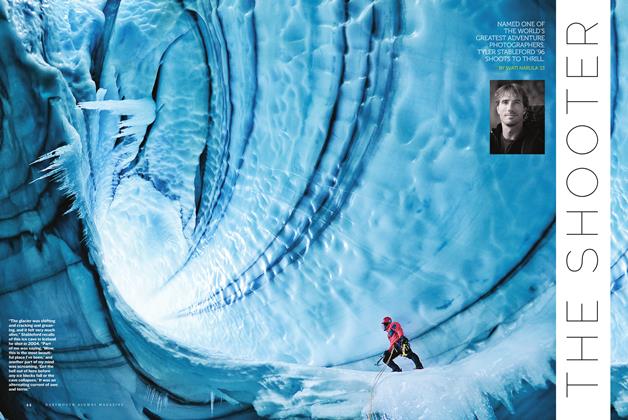

FeatureThe Shooter

Jan/Feb 2013 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13 -

Feature

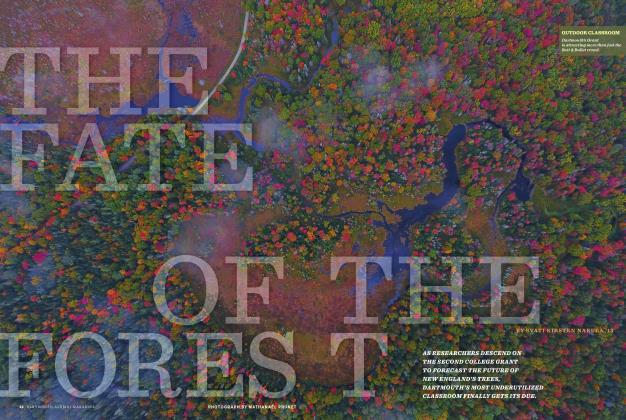

FeatureThe Fate of the Forest

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2020 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13