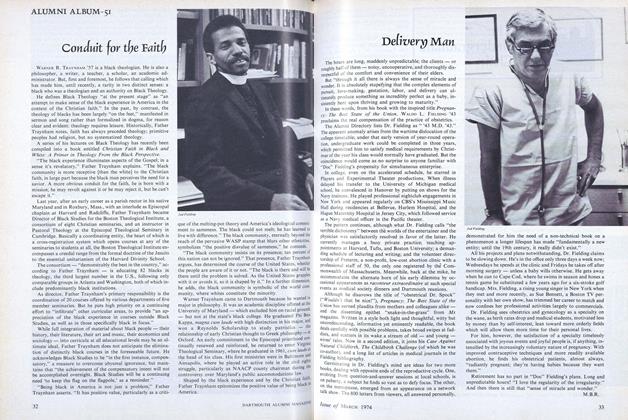

WARNER R. TRAYNHAM '57 is a black theologian. He is also a philosopher, a writer, a teacher, a scholar, an academic administrator. But, first and foremost, he follows that calling which has made him, until recently, a rarity in two distinct senses: a black who was a theologian and an authority on Black Theology.

He defines Black Theology "at the present stage" as "an attempt to make sense of the black experience in America in the context of the Christian faith." In the past, by contrast, the theology of blacks has been largely "on the feet," manifested in sermon and song rather than formalized in dogma, for reason clear and evident: theology requires leisure. Historically, Father Traynham notes, faith has always preceded theology; primitive peoples had religion, but no systematized theology.

A series of his lectures on Black Theology has recently been compiled into a book entitled Christian Faith in Black andWhite: A Primer in Theology From the Black Perspective.

"The black experience illuminates aspects of the Gospel; in a sense it's revelatory," Father Traynham explains. "The black community is more receptive [than the white] to the Christian faith, in large part because the black man perceives the need for a savior. A more obvious conduit for the faith, he is born with a mission; he may revolt against it or he may reject it, but he can't escape it."

Last year, after an early career as a parish rector in his native Maryland and in Roxbury, Mass., with an interlude as Episcopal chaplain At Harvard and Radclifife, Father Traynham became Director of Black Studies for the Boston Theological Institute, a consortium of eight Christian seminaries, and an instructor in Pastoral Theology at the Episcopal Theological Seminary in Cambridge. Basically a coordinating entity, the heart of which is a cross-registration system which opens courses at any of the seminaries to students at all, the Boston Theological Institute encompasses a creedal range from the formal doctrine of the Jesuits to the essential unitarianism of the Harvard Divinity School.

The consortium - "demonstrably the best in the country," according to Father Traynham - is educating 82 blacks in theology, the third largest number in the U.S., following only comparable groups in Atlanta and Washington, both of which include predominantly black institutions.

As director, Father Traynham's primary responsibility is the coordination of 20 courses offered by various departments of five member seminaries. But he puts high priority on a continuing effort to "infiltrate" other curricular areas, to provide "an appreciation of the black experience in courses outside Black Studies, as well as in those specifically black in focus."

While full integration of material about black people - their history, their literature, their art and music, their economics and sociology - into curricula at all educational levels may be an ultimate ideal, Father Traynham does not anticipate the elimination of distinctly black courses in the foreseeable future. He acknowledges Black Studies to be "in the first instance, compensatory," a measure to overcome abysmal ignorance, but maintains that "the achievement of the compensatory intent will not be accomplished overnight. Black Studies will be a continuing need 'to keep the flag on the flagpole,' as a reminder."

"Being black in America is not just a problem," Father Traynham asserts. "It has positive value, particularly as a critique of the melting-pot theory and America's ideological commitment to sameness. The black could not melt; he has learned to live with difference." The black community, eternally beyond the reach of the pervasive WASP stamp that blurs other ethnicities, symbolizes "the positive disvalue of sameness," he contends.

"The black community insists on its presence; ten percent of this nation can not be ignored." That presence, Father Traynham argues, has determined the course of the United States, whether the people are aware of it or not. "The black is there and will be there until the problem is solved. As the United States grapples with it or avoids it, so it is shaped by it." In a further dimension, he adds, the black community is symbolic of the world community, where whites constitute the minority.

Warner Traynham came to Dartmouth because he wanted to major in philosophy. It was an academic discipline offered at the University of Maryland - which excluded him on racial grounds - but not at the state's black college. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa, magna cum laude with high distinction in his major, and won a Reynolds Scholarship to study patristics - the relationship of early Christian thought to Greek philosophy - at Oxford. An early commitment to the Episcopal priesthood continually renewed and reinforced, he returned to enter Virginia Theological Seminary, where he graduated in 1961, cum laude at the head of his class. His first ministries were in Baltimore ant Annapolis, where he played an active role in the civil struggle, particularly as NAACP county chairman during the controversy over Maryland's public accommodations law.

Shaped by the black experience and by the Christian faith, Father Traynham epitomizes the positive value of being black in America.

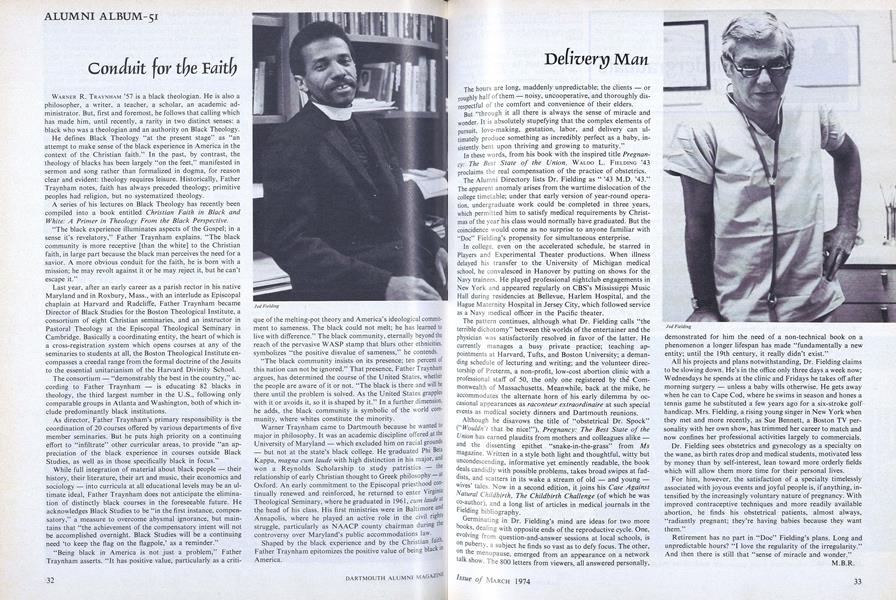

Jed Fielding

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJournal of a Long Season

March 1974 By TOM EGGLESTON -

Feature

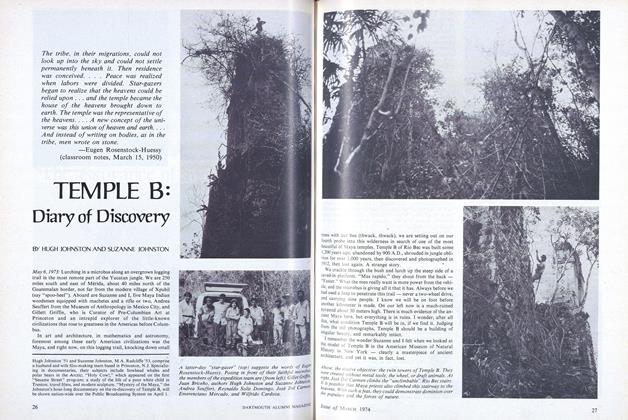

FeatureTEMPLE B: Diary of Discovery

March 1974 By HUGH JOHNSTON AND SUZANNE JOHNSTON -

Feature

FeatureDelivery Man

March 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

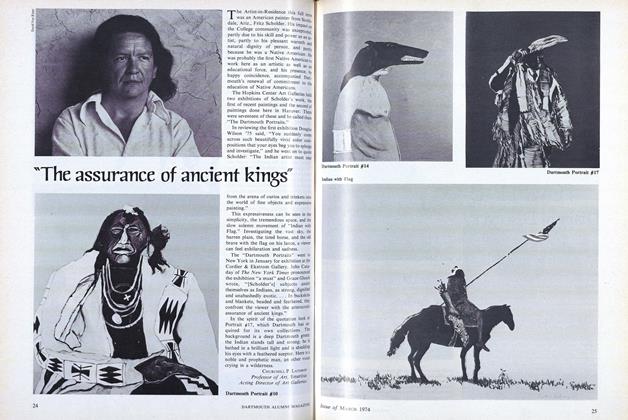

Feature"The assurance of ancient kings"

March 1974 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

March 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleThe Mystery of the Wah Hoo Wah

March 1974 By JOHN B. STEARNS'16

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryFavorite Places

Mar/Apr 2002 -

Feature

FeatureYORKE BROWN

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

Feature'... A whole pool of frustration, anger, resentment...'

February 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

FeatureConscience or Compromise

July 1961 By HARRIS BONAR McKEE '61 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTranslating Plato's Republic

DECEMBER • 1985 By Kathie Min -

Feature

FeatureThe Making of a Primary Winner

MAY 1968 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70