from his readers are sometimes an author's most satisfying reward. For one Dartmouth author, Prof. Harold L. Bond '42 of the English Department, whose Return to Cassino was published by Doubleday in 1964, such a letter was received from Italy a few months ago. But the reason for Professor Bond's letting the editors see it was not personal; rather he believed that what Fausto Fassio has to say of America and Americans, and the way he says it, would be in refreshing contrast to the barrage of "ugly American" criticism one usually encounters.

The letter follows:

DEAR SIR:

I beg your pardon, if I disturb you.

I am an Italian, ex-partisan, volunteer in the Italian Resistance. I wish to thank you with all my heart, because: (1) You have written a wonderful book: "Return to Cassino." (2) You have fought in order that to destroy the shame of the world: the nazifascismus. (3) You have fought for the freedom of my own country.

Since the glory days of our freedom, my life is a long thought of gratitude for the men who made free us, Italians, from the slavery, and every day (I say and repeat "every day") I think of them and often, when my heart is full with sadness and memories, I go to the "Milan War Cemetery," where many Allied soldiers sleep their long sleep, and I put a flower on their graves. It is a very modest sign of my perpetual thankfulness.

Dear Sir, reading your book, I have felt the strength of the far memories, when I was young, when I was slave under the nazi heel, and my soul was thirsty of freedom, and I loved my brothers: Americans of Clark, English of Alexander, New Zealanders of Freyberg, Polish of Anders, French of Juin, Australians, Brazilians, South Africans, Indians, Canadians: I loved them with all my heart, because all our hope of freedom was in them. We, then, were desperate men: in the long, dark nazist night, everything seemed lost; our name, the Italian name, was dishonoured in all the world, for the brutal fascist aggressions against all the world.

Those of us, who were not fascists, wanted to demonstrate to the world that not all the Italians were fascists, so we took the weapons and began our desperate struggle against the Germans and against their servants: the fascists. So we fought for us, for our families, for you, for all the men who suffered under the nazi heel.

It was a hard job: for those of us who were captured there was no hope, generally, of living: we were considered "out-law." So we gave our twenty years of age to the cause of the freedom. Sometimes, in the still of the night, I thought of the possibility to be captured, and my forehead became wet with sweat, because I was not a strong man, and my soul was a shy one but I continued my struggle, because the love for the freedom was greater than the love for the life.

Sometimes when I looked into the eyes of my sweet-heart (now my wife), j thought: "Perhaps it is the last time I 'see her," and I felt a terrible sorrow in mv heart, but I continued my struggle, because I wanted to live till the day on which my eyes could see the arrival of the Allied troops. I loved all them, with the same tenderness with which I love now my son Riccardo.

And God was indeed merciful towards me. At 10 o'clock in the morning of 3rd May 1945, at Golasecca, a little village on the River Ticino (a village, which we, partisans, had occupied), a unit of the American 34th Division arrived, at the command of a Captain Johnson. Dear Sir, I may live one thousand years, but I can't forget that moment. Before my amazed, enchanted eyes were the fabulous men of wonderful America, with their guns, which had fought at Cassino, their "bull-head" on the shoulders, their red handkerchief at the neck and the chewing-gum in the mouth. Tall, kind, smiling, they arrived like a magical vision.

Then my heart burst: I ran, how mad, to wards them, I embraced the first I met: a Fred Walling, from Johnson City, and I felt that the life had given me its most precious gift. ("Bliss had fulfilled its measure", as says the English poet Thomas Hardy.)

If it were possible, I would give the rest of my life, for feeling once more such a happiness. Never, never, never have I felt again such a sweet, pure, immense joy. those soldiers stayed in that village 10 days about and all became friends of mine: Captain Johnson, Fred Walling, Justin, Patterson, Smith, Bukovski, and all. They are always in my heart.

Thank you, American friends, once again, thank you, American brothers, everywhere you are, for the joy you gave me on that far 3rd May 1945! May God bless for ever your life.

Dear Sir, maybe you ask me why I write you these things. For remembering, Sir, only for remembering. To remember those days means for me to feel again warm my blood, to feel again a lost happiness. It's the same sweet, bitter melancholy I feel everywhen I listen to the music of your great Jerome Kern or Cole Porter: the music of my olden days, when to sing a "blues," forbidden by the fascists, was to demonstrate our immense love towards free America.

Twenty years have passed, but my love has not passed away. I keep it in the treasure of my heart, and often I speak to my son Riccardo of those glory days and I teach him to love your names, to love your graves, because if my son was born in freedom and has not known the nazist terror, he owes that to you all, Allied troops.

I'll never forget that, and so my life is a long thought of you. I wish to you, to your kind wife, to your daughters to live their life in happiness and peace. They must be nrnud to have a husband and a father, who fought for the freedom of all the men, in order that everybody might live with sweetness and tenderness.

Once again I tell you "Thank you, Dir. If vou will be so kind to write to me only two or three words with your own hands, I'll be proud to have the signature of such a kind and good writer.

Yours sincerely,

Milano, Italy

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStudent Activism at Dartmouth

May 1966 By RICHARD A. BATHRICK '66 -

Feature

FeatureThe Rewards Eventually Come in the Upperclass Years

May 1966 By NELSON N. LICHTENSTEIN '66 -

Feature

FeatureANGLOPHILIA HITS THE CAMPUS

May 1966 By ARTHUR N. HAUPT '67 -

Feature

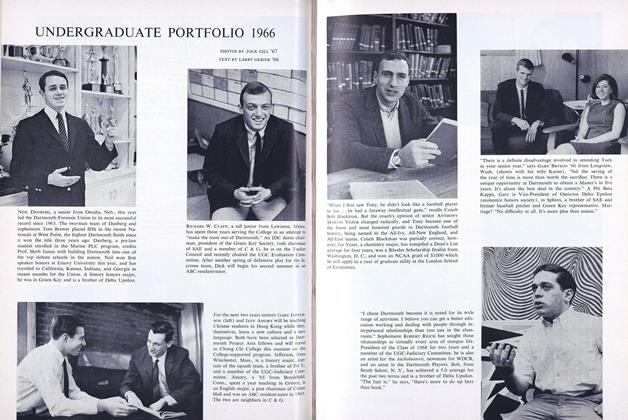

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE PORTFOLIO 1966

May 1966 By TEXT BY LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

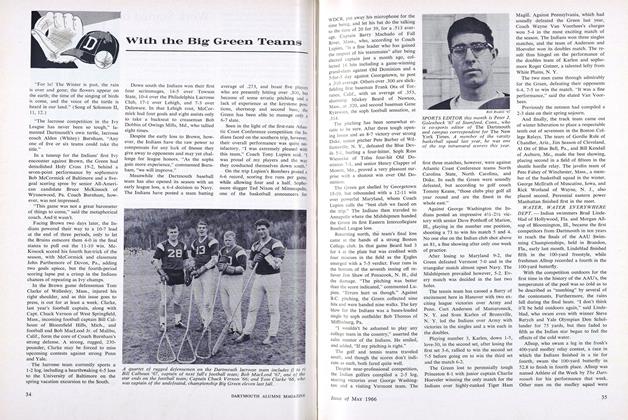

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

May 1966 -

Article

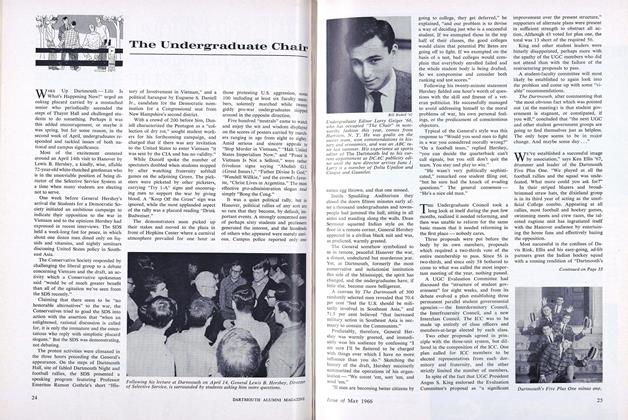

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66