A G. I. Suggestion

TO THE EDITOR:

Regarding the Great Issues course at Dartmouth (The Undergraduate Chair, April), might the problem not be resolved by rescheduling G. I. to somewhere earlier than the senior year? Might not the G. I. opportunity be provided, for example, to every eager, anxious-to-learn, starry-eyed, moon faced, and not-so-immature freshman?

By the time they reach the middle of their final year most undergraduates no doubt believe they already know something about "great issues" and hence are more ready to lecture to others than be lectured to. After some 35 years in which to rationalize this debatable question I find it uncertain that the seniors' viewpoint may not be a completely valid one.

New Haven, Conn.

"Who Is At Fault?"

TO THE EDITOR

That 200 Dartmouth seniors could walk out of a Great Issues session conducted by Richard P. Unsworth, Dean of the Tucker Foundation, because they did not wish to be lectured to on either "respect for persons" or "personal accountability." reflects more on the College as an effective institution, it seems to me, than on the students them- selves. And one has only to live in the vicinity of Hanover to know that the Unsworth episode is only an isolated flare-up of a disease that appears to be chronic with Dartmouth students today. Who is at fault?

You can pass the buck to parents, and this is a favorite device of educators. But this is not a valid excuse, because by the time a boy has entered Dartmouth, it is the College that exerts the greater influence. Of course, the pedagogues will rush to their own defense and say, "We offer the student all the opportunity in the world. He has only to avail himself of it. If he does not, he is immature."

This may be partially true. It may be true that "Education must be caught, not taught." But is the Dartmouth student given no effective and continuing guidance?

If it is the aim of Dartmouth to turn out men, and not mere thinking machines, it seems to me that the College administration should reassess its entire educational program to find out in what respects it has failed, and how the failure can be corrected.

I am not an educator, and my opinions will, therefore, carry little weight with professionals. But as an alumnus I have the temerity to suggest that compulsory courses be established for each of a student's four years, and that a few of the course titles might be as follows:

Ethical Behavior in a Civilized Society.

How to Behave Like a Man of Culture.

How to Live in a Predatory Society With out Becoming a Bird of Prey.

Why a College Graduate Can Not As sume That He Is the Center of the Universe

How to Recognize the Rights of Others Even Though It Hurts.

Orford, N. H.

Down With Pedaguese

TO THE EDITOR:

I have never written to the MAGAZINE before, but I can't refrain from telling how much I enjoyed the article in the March issue entitled "Pedaguese Made Easy." It was a delightful piece of satire which needed to be said, and gave me a feeling of "interrelationship" with the writer.

How many times have I tried to read articles in the MAGAZINE by learned (they must be) writers who may be professors and even students, with a dictionary by my side looking up unfamiliar words! Often I have ceased to read in disgust. Why, oh why should this be so? Am I just one of the few unerudite morons who should pursue further study? In college I majored in English, had plenty of Latin, Greek, German and some Italian, and for that reason can at times trace the root of some unusual word, but why must a writer or speaker confuse the reader?

As a lawyer, I have been trained to speak and write so as to be clearly understood. Otherwise, why speak or write? If one has to stop to look up the meaning of words often used in an article, one soon tires of the effort, gives up the struggle, and spends the time reading something written by someone "erudite" enough to be instructive and understood. Am I stupid or just a common person engulfed in a "surgent" wave of knowledge?

May I just say this also. A famous person once delivered the "Gettysburg Address," famous in all literature. Not a word that could not be understood by a primary pupil. Would that others might or could do likewise.

From a simple-minded person.

Portland, Maine

More Pedaguesianisms

TO THE EDITOR

When Mr. James LeSure produces his definitive compendium (dictionary) of academic verbiage known as "Pedaguese" he should be laurelled as another Noah Webster. I am particularly grateful for his explanation of "meaningful" and "in a very real sense."

I am glad to help your readers with explanations of a few other pedaguesianisms:

"interpersonal relationships": personal relations

"under-achiever": a dumb student

"structured for": prepared for

"teacher-scholar" (archaic): young instructor

"dialogue": formerly, a conversation between two actors; now, a Senate debate about Vietnam

"happening": formerly, an everyday occurrence; now, a weird art show

"seminar": a small class of advanced level

"freshman seminar": a large class of introductory level

"proseminar": nobody really knows

"colloquium": discussion

Hanover, N. H.

In Praise of Herb James

TO THE EDITOR:

The late John D. Rockefeller is reported to have said to a youngster who asked about where he should go to college, "I should find out where Dr. Ernest Martin Hopkins is President and go there." Remembering that this remark was made by a Brown alumnus and, applying the same objectivity, we could also say to a prospective student asking about where the standards of debate excellence are high, "Find out where Herbert James is debate coach and go there."

Dartmouth imported Herbert James from the University of Wichita where he had been an active debater for four years. This was followed by graduate study in following summers and an M.A. in Rhetoric and Public Address at Ohio State. Then came advanced study at the University of Florida and a return to Dartmouth in 1949 where he has taught with great distinction ever since. When James returned to Dartmouth, things began to happen, and, ever since, Dartmouth has built a national reputation for excellence in debate. In fact, if a poll were taken as it is in football and basketball, Dartmouth would be ranked among the top 10.

An index of Dartmouth's achievement in this important work is her standing in the National Debate Tournament, an annual event held at West Point. Dartmouth has won the National Championship twice and no other college has won more. Not at all incidentally, the rotating trophy of the National Debate Tournament is named for Sigurd Larmon '14 whose active and unflagging interest in the debate activities has contributed immeasurably to the outstanding success of Dartmouth debate teams.

Mr. James says, "Coaching debate at Dartmouth has been the most rewarding experience in my lifetime." The debaters are very bright and very devoted and a large percentage of these students, naturally, become lawyers and, understandably, outstanding men in their profession.

Thus does Mr. James give credit to the boys who come to him for guidance, but Emerson's dictum should be borne in mind: "An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man." So let us not take debating excellence at Dartmouth for granted, but rather let us concede that Mr. James works with a group of earnest and devoted young men who, under his careful and experienced guidance, have made Dartmouth debating achievement something of which every one of us should be proud indeed.

New London, N. H.

"New Life" in the Classics

TO THE EDITOR

I have read with much interest and delight the article, "Dartmouth's 'New' Curriculum," in the April issue of the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE. Its sweep is breathtaking, especially to this reader who joined the faculty already midway in the period of your review. And I greatly appreciate the impact that our growth in Classics, however modest, has made upon one viewing the extent of change over the years.

Doubtless there are many details of the expansion in Classics which could not be included in fairness to similar growth in the other disciplines. But I hope you will not take it amiss if I were to mention several smaller indications of "new life" and change of which we are rather proud. A new major, Greek and Roman Studies, was introduced in 1962, I believe, in which students could elect a combination of either Greek or Latin with related courses in Greek and Roman archaeology, history, drama, and ancient philosophy. This flexibility has increased the number of majors considerably, especially among students who are not planning a professional career in the Classics. In the years 1965-66 the number of majors doubled from about 8 to around 16, of whom half are Classics and half Greek and Roman Studies.

In 1963 we completely revised our curriculum, rewriting all the course descriptions and inaugurating a new program in the Greek and Latin authors in two- and three-year cycles. A total of 16 new courses in the authors have been added, as well as Greek Archaeology, Roman Archaeology, Classical Drama, Greek Mythology, and Ancient Political Institutions; also a Seminar in Greek art and architecture. The courses in Classical Archaeology which for many years were taught by Prof. John B. Stearns in the Art Department are currently included in the new Classics program. Greek and Roman Literature in Translation (2 courses), the former Classical Civilization, is now taught in sections of 20 to 25 students each. These courses, with the continuing encouragement of our esteemed and beloved Professor Nemiah who established and built the tradition, have thrived, the enrollment averaging annually around 700 students. We are very proud of the fact that these sections are taught by highly trained faculty, where in many a large public university such assignments would be given to rather inexperienced graduate students. It is in these courses that we try to give the College the best of our understanding of the Classical tradition and thought.

Next year we plan to offer Greek 1 in the winter term, in order to devote the fall term to building up more interest in the language. We have introduced Modern Greek and Medieval Latin, as well as New Testament Greek to expand the range beyond the classical era. And the students themselves have organized a Classics Club for the reading of students' papers. The Club meets fortnightly and at present there is actually a backlog of papers on the roster. Beginning last year, we instituted a series of College Lectures in Classical Literature and Archaeology, one each term. By the close of this year we shall have had both the Regius Professors of Greek at Oxford and Cambridge, Hugh Lloyd-Jones and Denys Page; the former director of the Greek and Roman department of the British Museum; Viktor Poeschl, professor at Heidelberg; our own Richmond Lattimore '26; and Henry Rowell from Johns Hopkins, editor of the American Journal of Philology.

Much of this goes beyond the limits of curricular change and I have written as much out of enthusiasm as factual growth But I believe the Classics at Dartmouth are now beginning to gather a reputation beyond this campus for which we can thank equally a lively group of younger men on the staff and curricular change and expansion in the early and formative years of our new growth.

Chairman, Department of ClassicsHanover, N. H.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

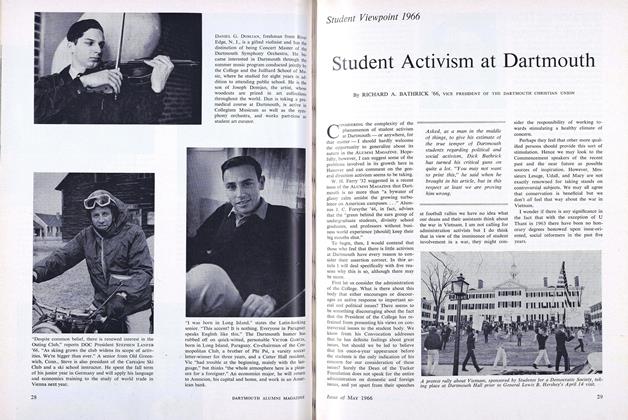

FeatureStudent Activism at Dartmouth

May 1966 By RICHARD A. BATHRICK '66 -

Feature

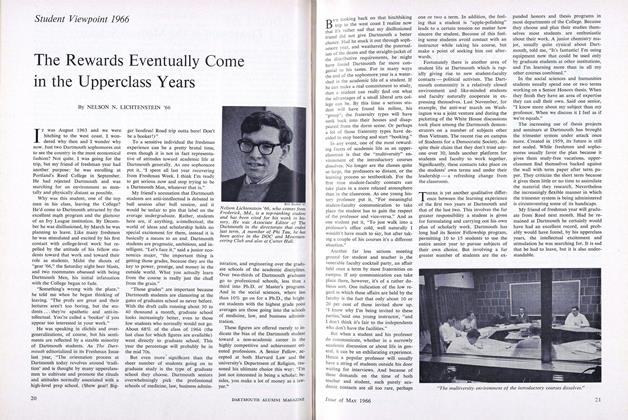

FeatureThe Rewards Eventually Come in the Upperclass Years

May 1966 By NELSON N. LICHTENSTEIN '66 -

Feature

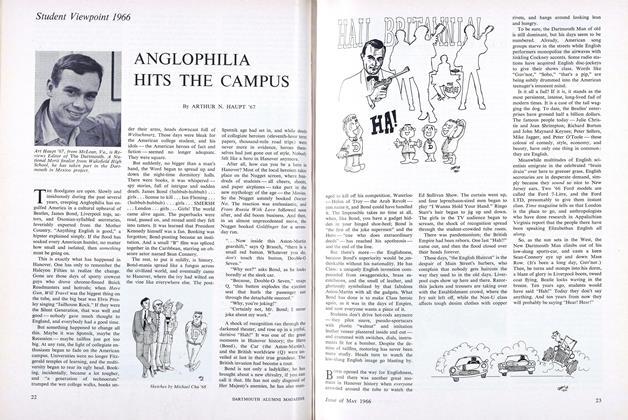

FeatureANGLOPHILIA HITS THE CAMPUS

May 1966 By ARTHUR N. HAUPT '67 -

Feature

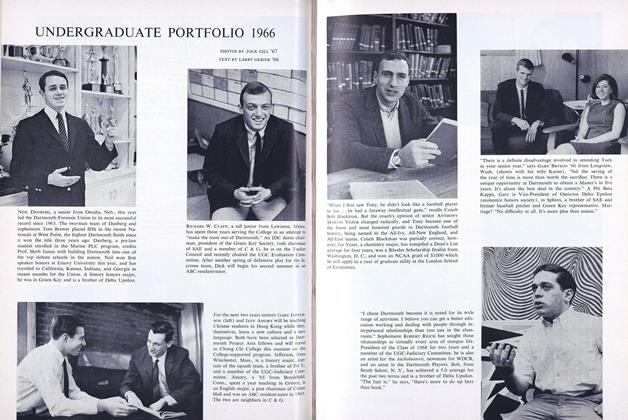

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE PORTFOLIO 1966

May 1966 By TEXT BY LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

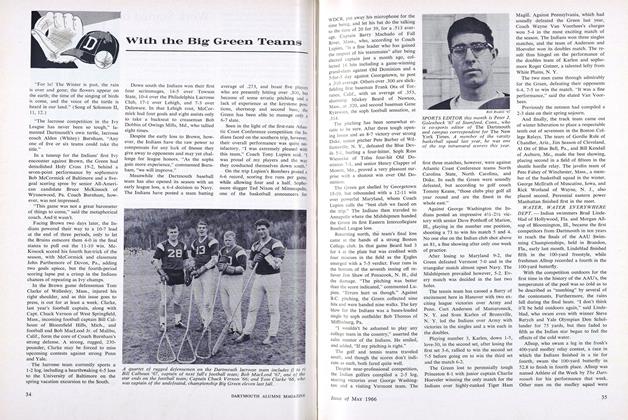

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

May 1966 -

Article

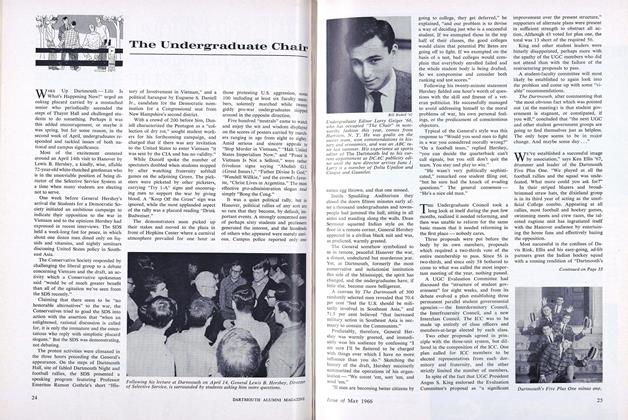

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66