THE COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

'66, CHAIRMAN, U. S. CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION

MY gratitude to Dartmouth on this occasion takes many forms. My honorary entry on the rolls of Dartmouth degree holders fulfills a long-time aspiration which was originally kindled in a pre-admissions interview in a circle of ardent alumni in 1934. For reasons, more than adequately explained in my official biography, it has taken nearly 32 years, rather than the standard four, to acquire my degree. But, perhaps because of the longer time served, the Faculty and Trustees have shortened the residence requirement in my case.

I am grateful to Dartmouth, particularly to the editors of its newspaper, for preserving my official state of anonymity. That editorial entitled "Who Is John Macy?" effectively re-established my credentials as a Washington practitioner of passionate anonymity. These credentials had been seriously threatened in recent months by increasingly frequent descriptions of the President's talent scout and his operations. My gratitude on this count is only matched by that of the President.

But my gratitude to The Dartmouth extends even further. I was provided with a new definition of "G. 1." Out of my pre-Dartmouth ignorance I had assumed these ubiquitous initials .stood for "government issue" or "gastro- intestinal." But, instead at Dartmouth, they represent, or did until recent Faculty action, "Great Issues." Let me assure the graduating class that I have no intention of offering "greetings" on this occasion which are G.I. in any of these definitions.

Recognizing, with some humility, the high quality and renown of those who have occupied this commencement rostrum on previous occasions, I conducted a brief study of the identification and remarks of those previous speakers for possible clues as to speech content which might appeal to the graduates of this day as a compensation for the anonymity of the speaker. I discovered that in 1953 Dartmouth graduates were privileged to hear the President of the United States. I felt certain that his remarks would give me some indicators as to the oratorical fare most appreciated by Dartmouth men. The Presidential papers, however, were of very limited assistance. The Chief Executive exhorted the Class of 1953 to have fun and to have courage. I heartily subscribe to such exhortation. But, since these qualities are standard characteristics possessed by all Dartmouth men, any lengthy reiteration at this time would obviously be superfluous and redundant.

Instead, I accept the privilege of this platform to speak directly to the graduates in my capacity as the Federal official with primary concern for the future quality staffing of public service.

WHEN the members of this class reach the advanced age of 55, the year will be 2000. You will be members of the prime leadership generation on the eve of the 21st century. The promise and the problems of that seemingly infinite date will be the reality of your time. Certain conditions of that day have already been predicted by the forecasters with the aid of statistical data, historical trends and the marvel of the computer. They predict that the population will approach 315 million, 125 million jobs will be needed, average income will be $6,000 and average hourly pay $7.50. Nine out of ten Americans will be living in supercities or their suburbs. In technological developments, thirty years of moon exploration will have been completed, commercial supersonic flight will have further contracted time and space in global travel, satellitebased communications will have further linked all people, and artificial control of climate and even human behavior may be within the grasp of man.

But what of the quality of life for Americans in the year 2000? Can social and political developments keep pace with the accelerated change generated by science and technology? What forms of future governance will Americans evolve to assure that fundamental principles of democracy and individual freedom are not sacrificed in the name of material progress? What safeguards can be erected to protect the citizen from negative or destructive by-products of growth and change?

There is a growing awareness in university, business and government circles of the necessity to be future-oriented and to explore systematically the possible future for our nation and for the international community. At the moment, a number of serious proposals for the creation of research institutions focused on the future are in the process of development. They are aimed at providing the knowledge, conceptual tools and services necessary for Proved planning and policy development by leadership forces in the country and contributing to the creation of a better informed public with respect to the needs for the future.

Ability to plan with greater reliability for the future becomes increasingly important as the pace of change accelerates Since the Renaissance the western world has pursued change as a way of life. Soon after the formation of the American republic, de Tocqueville remarked on the disposition of its citizens to cherish change. Yet, even in the United States change has not always been purposeful nor have its consequences always been welcome. Today because resources available to governments are immeasurably greater than ever before and the courses of action taken by governmental and private agencies are inter-acting in more intimate and complex ways, we are becoming more concerned over the need to understand what is implied by alternate courses open to us. The decision makers of the future must be equipped with the products of such forward thinking generated by the best minds with the most advanced techniques. Here is another area of intellectual pursuit where the universities can contribute fruitfully to the national future through research and scholarly discussions. The liberal arts institution possesses assets peculiarly suited to such study. It offers the broad sweep of learning and the opportunity for a congenial interdisciplinary approach. Perhaps a research seminar addressed to the solution of basic future problems would prove a challenging successor to the Great Issues program at Dartmouth.

IT is over this bridge from the present to the future that I would transport you from the world of academia to the problems of public service. The catalog of public problems is large and diverse. The determination of priorities for action difficult and hazardous. But I would identify and describe one with an imperative for immediate action - action which must build toward that distant future: the social and physical problems of our cities. Yes, in 2000, 90 percent of Americans will live in the metro- politan complexes of our country. These will be the centers in which you work and live - unless, of course, you find some way to remain in Hanover. In all likelihood, your work will be pursued in the core city, your home will be in suburbia or exurbia. This living pattern may permit an escape from the critical needs of the city. But it is increasingly unlikely. The interrelationships of metropolitan existence will be too compelling to permit escape.

The keynote for action on the urban front was sounded by the President in his description of the objectives of the Great Society. He called for "a place where every child can find knowledge to enrich his mind and enlarge his talents. It is a place where leisure is a welcome chance to build and reflect not a feared cause of boredom and restlessness. It is a place where the city of many serves not only the needs of the body and the demands of commerce, but the desire for beauty and the hunger for community." And specifically for the city, he said, "It is harder and harder to lead the good life in American cities. The catalog of ills is long. There is the decay of the centers and the despoiling of the suburbs. There is not enough housing for our people or transportation for our traffic. Open land is vanishing and old landmarks are violated."

The rising and inescapable tide of urbanization is bringing with it two dire and drastic problems the problems of urban decay and the problems of urban growth.

The hearts of our cities are rotting.

The human cost of urban decay is high and alarming.

The poor, the disadvantaged, the discriminated against are increasingly concentrated into tight, squalid ghettos- deprived of a decent environment, with little opportunity and less hope. This is the gray, ill-prepared, tragic driftwood of our otherwise affluent society.

We must concentrate every available resource — in planning, in housing construction, in job training, in health facilities, in recreation, in education - to improve dramatically the living conditions of the urban core. This will require a great and concerted effort on the part of local leadership, both public and private.

While the nation has been making gigantic strides in space and defense technology, our cities are still operating with many of the same techniques and traditional assumptions they have used for decades. It is not necessary to do more than list a few of the neglected areas in our domestic society - poor schools, inadequate medical care, air and water pollution, traffic congestion, rundown housing, formless urban sprawl and human deprivation. Currently, large expenditures are made to mitigate these conditions, but relatively little effort is being made to find new or improved ways of attaining long-range urban objectives. This situation must be changed if our cities are to reap the benefits that can be provided by American ingenuity.

There is a rising desire on the part of urban leadership to search out new and better ways for attacking the problems of city management, planning and resource allocation. However, in terms of the magnitude of the problems, too few imaginative people from many different disciplines have been mobilized to find new approaches.

IT is the mobilization of talent and imagination to attack these problems that constitutes an urgent demand upon public administrators. The needs are evident in every profession. Public service to build better cities demands the engineer and planner, the teacher and social worker, the doctor and health technician, the lawyer and manager. But the demand is for the specialist with broad view and with the public commitment. The shortage is critical in every major city for administrative, professional and technical manpower.

The city must also become the arena in which renewed and special efforts are made to complete democracy's unfinished business - the true equality of the Negro in American society. Although our attention is drawn by shock and disbelief to the conditions of inequality in the rural south, concentration on northern urban failures is imperative if equality is to be a reality as well as a recently reaffirmed legal fact. No American can be exempted from a part in fulfilling the rights now recognized and expressed by Congress in the civil rights statutes of the past two years, and hopefully this year, and by court decisions over the past twelve years.

The reasoning and emotion of the recent White House conference to fulfill these rights impressed all present, white and Negro, from across the country that we must now move from opportunity to achievement, and as the President expressed it at Howard University a year ago - "to shatter forever not only the barriers of law and public practice, but the walls which bound the condition of man by the color of his skin.

"To dissolve, as best we can, the antique enmities of the heart which diminish the holder, divide the great democracy, and do wrong - great wrong - to the children of God."

We must find the means for eliminating the black ghettos and for breaking the white suburban noose around our cities. We must remove the disability of segregated education, whether imposed by de facto conditions or past practice. We must develop and share with all Americans the assets of culture and natural beauty. We must move from protest demonstration to the demonstration of actual change and progress. We must face the difficult task of organization for action and problem solving. We must contribute our individual capability in a special public service to overcome America's long-term human disability.

THE necessity of the years leading to the century's end will not be limited to this urban portion of the public sector. The problems of international relations, national security, research and development will place their demand for the participation of the talented in all professions. But this urban problem area is more critical and more immediate. In these real and ever-present public issues are the opportunities for the type of public service Plato described so long ago-

"But when their turn comes, toiling also at politics and ruling for the public good, not as though they were performing some heroic action, but simply as a matter of duty."

In a widely read report last year John Gardner sounded a warning and a plea for future leadership when he discussed the subtle and powerful ingredients of "the antileadership vaccine." I prescribe the antidote to this vaccine in a call for public service leadership drawn from the many intellectual disciplines and diverse professional preparations for the improvement in the quality of urban life. The Dartmouth high tradition of solid liberal arts education provides the ideal foundation for such a service of commitment.

Yet this service involves many patterns. I tend to encourage a total career. But there are other equally effective options - the volunteer service with VISTA (the domestic Peace Corps) or the Teachers Corps for the short term; the "in and out" service with a combined public and private career, the "extracurricular" service in after-hours contributions of time and talent.

When he stimulated the Federal service with his standard of "a proud lively service" and invited "daring and dissent" to foster ideas and innovation, President Kennedy was reflecting his personal philosophy derived from the Greek concept of happiness - "The exercise of vital powers along lines of excellence, in a life affording them scope."

Public service, then and now, affords just such an opportunity. The accumulated vital powers in leadership and performance is an essential in preparing the way for a 21st century not only quantitatively enormous and technologically beyond imagination but with freedom and opportunity enhanced and the quality of life for all mankind improved.

May these fine Dartmouth years lead on to some public service for your community and your country. May the talents and capabilities developed here contribute to the drive for peace, progress and human development.

In closing I offer a commencement prayer to sum up these aspirations in the words of Stephen Vincent Benet as distributed by Adlai Stevenson as his final Christmas greeting -

Grant us a common faith that man shall know bread and peace - that he shall know justice and right- eousness, freedom and security, an equal opportunity and an equal chance to do his best, not only in our own lands, but throughout the world. And in that faith let us march toward the clean world our hands can make."

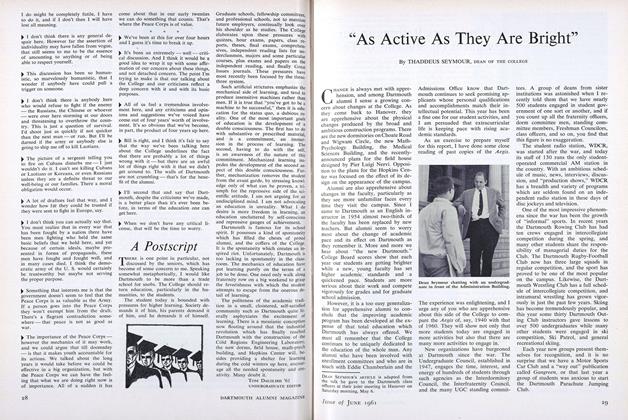

John W. Macy Jr. delivering the Commencement Address.

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePresident Emeritus Hopkins Is Honored With Dartmouth's First Alumni Award

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureRetiring Professors

June 1974 -

Feature

FeatureThe Philosophy of Culture

DECEMBER 1966 By ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32 -

Feature

FeatureAn Honor, To a Degree

Sept/Oct 2002 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

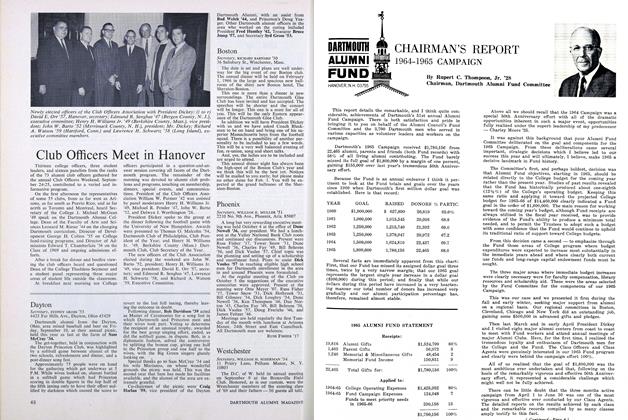

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

NOVEMBER 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28 -

Feature

Feature"As Active As They Are Bright"

June 1961 By THADDEUS SEYMOUR