THE FIFTY-YEAR ADDRESS

AT THE outset, I might as well warn you that this will not be a second Gettysburg Address, ringing down through the ages. Nor will it attempt to solve the problems of Vietnam or the Great Society or compete with the Commencement Address.

In 1963 my good friend, Don Cunningham, making the fifty-year address, reminded his audience of the advice given by Professor Craven Laycock (later Dean Laycock) to his class in rhetoric:

"If anyone is fool enough to ask you to talk, you be fool enough to talk." Although not certain of the correctness of this advice, I am following it in this instance.

The diverse nature of this audience makes my assignment especially difficult. To talk to alumni, and particularly to classmates alone, is no great problem. They are too far gone to justify the handing out of any advice. They like a little humor, and, above all, they demand brevity, so that they can get back to the tents. But when you add the graduating class, and their parents, wives, and other relatives, you are in trouble, because some words of wisdom are probably called for, although my children and grandchildren have assured me that even the young dislike too much preaching.

Another difficulty confronting the speaker on this sort of occasion is to find an appropriate title. After lengthy and agonizing rumination, I selected the title REFLECTIONS, because it seemed to afford me leeway to talk about everything or nothing in particular.

Most speakers have another problem. Shall they write out and read their speech or shall they talk from notes? In my case there is a danger in relying exclusively on notes without a complete text in front of me- This is due to sudden lapses of memory which apparently are one of the disadvantages of reaching threescore and ten. It reminds me of the story of the man who went to the psychiatrist and told him that he could not seem to remember anything. The psychiatrist asked, "How long has this been coming on?" To which the patient responded, "How long has what been coming on?"

Although, in view of all the difficulties, I am not too happy about being here in this role, I can nevertheless subscribe to what the late, great comedian, W. C. Fields, wrote as his own epitaph, to be in scribed on his tombstone, and I quote: "On the whole, I'd rather be here than in Philadelphia." No offense intended ]. could just as well have been Brooklyn or Kalamazoo.

My roots in Dartmouth are deep, father graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1878 and was a speaker at his commencement exercises 88 years ago. Some years later he composed part of the music for the first Dartmouth songbook, and he was always a loyal and devoted Dartmouth man, who brought me up on the idea that there was no other college worthy even of my consideration.

Two of my cousins also were Dartmouth men. One was a first cousin and the other a first cousin once removed. As a matter of fact, so far as Dartmouth is concerned, they were both removed. I have never pried into the whys and wherefores of their departure, but suspect that it had to do with scholastic performance, or, to be more accurate, nonperformance. Despite their removal, both gentlemen maintained an enormous enthusiasm for the College, and the older one, ex-'05, returned to Hanover regularly every June, regardless of whether or not his class was having a reunion, bringing with him a humorous and variegated group of friends, Dartmouth and non- Dartmouth.

In addition to the aforesaid blood relatives, known to us lawyers as relatives by consanguinity, several of my relatives by affinity, popularly (or unpopularly) known as "in-laws," attended Dartmouth. These were my brother-in-law and his three sons. These relatives by affinity did better as a group than my relatives by consanguinity. None of them flunked out, although one was suspended for a semester because of concentrating on the Saturday Evening Post instead of his studies. These also are wildly enthusiastic Dartmouth men.

All of this assortment of relatives belong to the same fraternity, with the exception of the youngest "in-law." Although the rest of us regard this maverick as a sort of odd-ball, we are polite enough to sit at the same table with him at Dartmouth gatherings, especially when he is accompanied by his wife, a young lady of beauty and charm.

Strangely enough, among this group of relatives, including your orator, there were no outstanding athletes. Indeed, probably my father led us all in this department, for he held the College championship for running 100 yards backwards, whereas none of the rest of us could even run 100 yards forward.

My brother-in-law played third- or fourth-string quarterback on a small preparatory school team. While he was being visited by a fraternity group during his freshman year at Dartmouth, the subject turned to football, and he gave some detailed and emphatic advice about assuring a successful season for the Dartmouth varsity Unfortunately, as he learned later to his dismay, one of his visitors was the captain of the Dartmouth team. My relative did not get a bid to that fraternity. but his loss (if any) was my gain, for had he not joined my fraternity, I probably would never have met his sister.

As for myself, I barely made one of the club teams in baseball at prep school (every boy had to play on one), and distinguished myself by invariably striking out with the bases loaded, thereby causing bitter tears on my part and disgust from my teammates.

At Dartmouth I bowled last man on the fraternity bowling team, and our fraternity stood last in the interfraternity bowling league. Eventually, I was removed from the team. My only satisfaction was that it continued in last place.

The most exciting relative by affinity was my brother-in-law's sister, who, to paraphrase Oscar Hammerstein, I saw one enchanted evening across a crowded room, during the junior prom festivities my senior year. After buying up most of her program dances at a dollar apiece (cheap enough, all things considered), and making a general nuisance of myself chasing her all over the campus, finally, on the third evening of our acquaintance, I asked her to marry me, and was accepted rather reluctantly on a tentative basis. This ceremony took place in the parlor of the Hanover Inn, at a spot now part of the gift shop. Though I have searched quite thoroughly, I have not found any shrine or plaque marking the spot.

It is trite to say that Dartmouth has changed and progressed since the Class of 1916 left it. One major change even long before our time is worth noting. An early publication of "Dartmouth University" contains the "Order of Exercises for Commencement," August 26, 1820. Here it is: Sacred Music, Prayer, Latin Oration, English Oration, Sacred Music, Philosophical Oration, English Oration, Sacred Music, English Oration, Latin Oration, Degrees Conferred, Sacred Music, Eulogy, Sacred Music. Who says the good old days were the best?

Since our graduation, the physical and cultural changes at the College are amazing. Hanover is no longer an isolated hamlet in the wilds of New Hampshire. It is an international cultural center. Many people consider the abolition of mandolin clubs a cultural change for the better. I remember vividly the concerts, in which we picked away vigorously for the questionable enjoyment of an audience mostly female, who could scarcely wait until the concert was over so they could dance. The favorite piece on all mandolin club programs was La Cinquantaine. It started like this: (speaker rendered a few bars imitating mandolins). Despite nine years of French, I never knew the exact meaning of the title, and now I can t even spell it, nor do I recall the gender. Imagine my joy when, in trying out for the Dartmouth mandolin club, the first piece placed before me was my old friend LaCinquantaine. Perhaps it was an overdose of La Cinquantaine that finally killed off mandolin clubs.

When we direct the subject of change to an appraisal of our classmates, we face a peculiar sort of dual mental state. We are conscious of the fact that they cannot look exactly the same after fifty years, yet when we see them, they don't look very different from the boys we knew so many years ago. Of course, the beautiful blond curls are often missing, but through a sort of nostalgic haze, we see them as they were in those halcyon days when we were young and gay. One thing definitely does not change though years may pass: these men are still our friends, and we are bound together by ties of College and class.

Upon entering Dartmouth in the fall of 1912, I found it a friendly place. Although I knew only two men in my class at the beginning, it did not take many months before all or most of our class were on a first-name basis. My roommate had an excellent system. If he passed someone on the campus whose name he was not sure of, he always said, "Hello, Mac," unless the man had red hair, in which case he said, "Hello, Red." Apparently the system worked satisfactorily as no one ever argued with him about it.

One unifying factor in our class, which was not intended as such, arose from a new elective course. It was taught by a new professor, the Reverend B. F. Marshall, and was entitled;- "Biblical Literature." We swarmed into it because for some inexplicable reason we thought it would be a "snap" course. Wow! How we misjudged the good reverend! We had to work harder in that course than in almost any other. But the association with so many dismayed classmates, bound together in a common disillusionment, resulted in the formation of many close friendships which remained with us through college and in later life. For this, we may thank the Reverend Marshall, even though his grade shocked us.

One early adventure at Dartmouth which has always stayed in my memory is concerned with the beloved Chuck Emerson, who was then Dean Emeritus of the College. My cousin, to whom reference has already been made, told me to be sure to get in touch with Dean Emerson, who would undoubtedly invite me over to his house and introduce me to "the girls." The prospect of meeting "the girls" was a pleasurable one, and I lost little time in calling the good dean who, as predicted, invited me to his home for an evening, saying that "the girls" would be at home and would also look forward to meeting me. With a fast pulse rate at the thought of "the girls," I shaved, and dressed carefully in my best $30.00 suit, the top quality of the era. Imagine my surprise and chagrin when "the girls," who were the dean's daughters, turned out to be in their fifties - young to us now, but not to a boy of eighteen. As it turned out, this was a practical joke engineered by my cousin, who, despite his previous separation from the College, thus rerevealed a certain ingenuity, which, had it been directed toward his studies, might have resulted in his graduating from Dartmouth, perhaps even cum laude.

I suppose that some observations from the Class of 1916 about life and the art of living would not be amiss.

The first item is given with tongue in cheek. Don't expect your wife and children to take you and your accomplishments too seriously. At an alumni dinner in his honor, the new dean of the Yale Law School gave as an example of this admonition a conversation with his wife a few days prior to the dinner. She asked him what he proposed to talk about at the dinner, saying, with what he called "that helpful kind of wifely confidence," "Are you going to rehash that sermon on the Bill of Rights which you gave in Philadelphia last week?"

Years ago I slaved over the preparation of a speech to be delivered to bar associations. It bore the non-sexy title "Actions Against Nonresident Motorists." Whenever I was invited to give a talk of any kind, my wife would say, in that disdainful tone employed occasionally by female spouses, "I suppose you're going to dish out Actions Against Non- resident Motorists' again."

Along a similar vein, when my son was around twelve years old, he suddenly informed me that in American law a man is presumed guilty until proved innocent. Having taught criminal law for fifteen years, I told him that the American law was exactly the opposite. He told me that I was wrong. I asked him where his information came from. He told me that it came from Ed Sheridan. Ed was a delightful and garrulous handyman who worked for my father-in-law. To cap the climax my son added, "And he knows more than you do!"

Thus, thanks to wife and children, we are restrained from becoming too self-satisfied and smug.

Now for some more serious observations.

I think it is important not to become downhearted or embittered over missing out on promotions, honors, or awards upon which you have set your heart. It is normal to want appreciation and recognition, but sometimes the other fellow will get them instead of you. Credit is not always given where credit is due, but you must learn to swallow your disappointment and carry on. As some author, whose name escapes me, has written: The true sign of a valiant man or woman is the decision to push ahead when the greatest favors of the world go to others, often unjustly."

Secondly, it is important to do thoroughly and conscientiously whatever tasks lie before us. In these times, too many persons are doing their jobs just well enough to get by. They lack that conscientiousness which impels a person to put his utmost effort into the task at hand. To them the coffee break is of more concern than the quality of their work. When a person fails to do his best, he is cheating the persons depending upon him, and he is cheating himself out of the satisfaction which comes from a job well done.

While we are speaking of jobs, I think we should warn you of the younger generation that every job has its hours of drudgery and routine, and that sometimes you may be tempted to quit because looks greener. While I do not mean that you should never change jobs, I do suggest that you should do so only after a great deal of investigation and thought. The grass on the other side of the fence may have its bare spots, too.

We should all practice the human sympathy and understanding which we call "tolerance." This involves the willing- ness to tolerate difference of opinion, and is the only atmosphere in which intellectual and humane achievement can flourish. Will Rogers once said, "Everybody is ignorant — only on different subjects." We should not assume that because the other fellow has a different opinion from ours, or does not seem to know much about a subject in which we are learned, he is therefore a nincompoop. Even though we disagree with him, let us try to understand his point of view.

Similarly, we should not pass judgment upon our fellow man without knowing all the facts. Rumor can be ruinous. I recall distinctly that during World War I a rumor spread through the country that a high official in the federal government had arranged for his son to escape the military draft. The fact was that his son was only eleven years old at the time. Think of the harm done to an innocent and fine man because of a failure to get the facts.

We should be kind and thoughtful. I remember as though it were yesterday the wise headmaster of my preparatory school exhorting us over and over again to "think about the other fellow." It has been said that the finest autobiography that any man can write consists of little words of kindness stored up in a loved-one's heart. Garry Moore said it at the conclusion of each of his television shows: "Be kind to each other."

As a corollary to being kind, it is also important to make known our appreciation of kindnesses and courtesies extended to us. It is amazing how deficient many people are in this respect. If someone is willing to take the time and trouble to show you a kindness or courtesy, the least you can do is to thank him.

Other observations which I am sure that members of my class share with me are that family life is a precious and sacred thing; that we wish we had not fussed and fumed so much about little, unimportant things; that while we should engage in civic activities, we should no, do so to such an extent as to neglect our families; and that we must have the courage to make decisions as we see the right, realizing that we cannot please everybody.

In addition, I am certain that we have come to the conclusion that happiness lies within ourselves and that we play the chief role in determining whether to lead joyful or gloomy lives. We know too, that to achieve happiness we must not forever yearn for the past nor depend too much upon some future event Happiness is a day-to-day affair, and we must catch it while it is upon us. A wise woman once wrote:

"For this is the way of our years and the way of our foolish hearts, that we hold each happiness lightly when it is upon us, and never really recognize it until it is forever lost."

This we must strive to avoid, and instead appreciate and enjoy the beautiful things of life while they are upon us.

I think that we of the Class of 1916 have lived long enough to realize that, with all its ups and downs, life is mighty sweet, especially for those of us who have enjoyed the great advantage of an excellent education. When I compare our lot with those of the poverty-ridden, illiterate hordes which I saw in India and Morocco, I wonder why we ever complain.

And it was at our beloved Dartmouth that we received probably the major part of that education. I know that we are proud to be Dartmouth men and that our affection for the College has grown continuously over the years.

On this day, when fifty years have passed since we left college as young men, eager to succeed and to mold a better world, we should not look back with despair over failure to achieve all our goals or to reach the heights of which we dreamed when we were 22. If we have done our jobs faithfully and conscientiously; if we have tried to be good husbands and fathers; if we have helped in some way, big or small, to make some people happier because our life has touched theirs; then I think that we should feel satisfaction in the thought that we have contributed something to the betterment of the world and to the happiness of those who have known us.

To the Class of 1966, I hope that you will have the wisdom and the will to make the world a better place, as we old boys have tried to do; and that your lives will be filled with satisfaction and happiness.

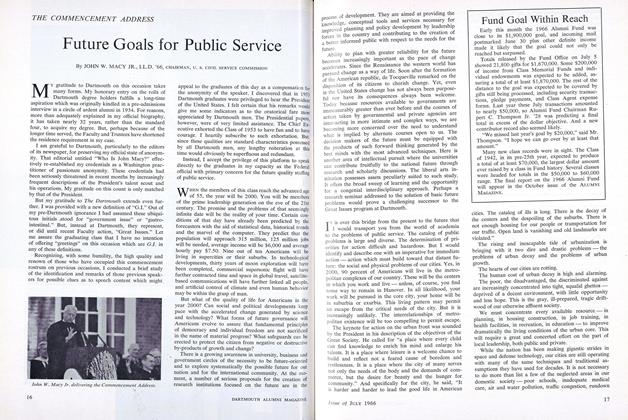

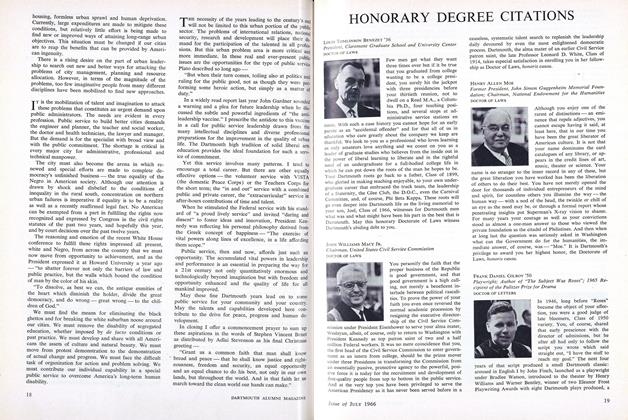

Fletcher R. Andrews '16 (r), 50-yearspeaker, and President Dickey at theCommencement luncheon. Mr. Andrewsis a noted lawyer and former Dean ofWestern Reserve University Law School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

FLETCHER R. ANDREWS '16

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA BIG NIGHT AT THE WALDORF

March 1958 -

Feature

FeatureNovelist on the Go

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Cover Story

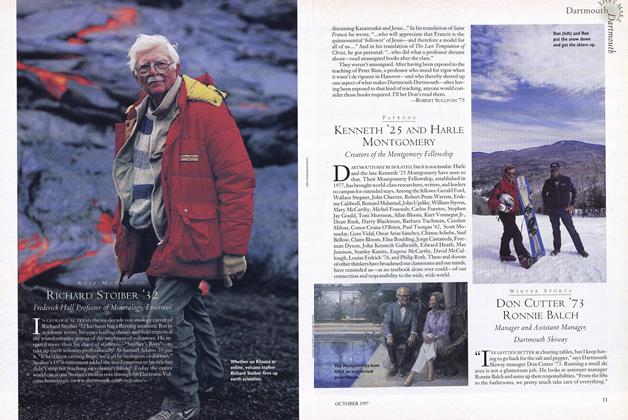

Cover StoryRichard Stoiber '32

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

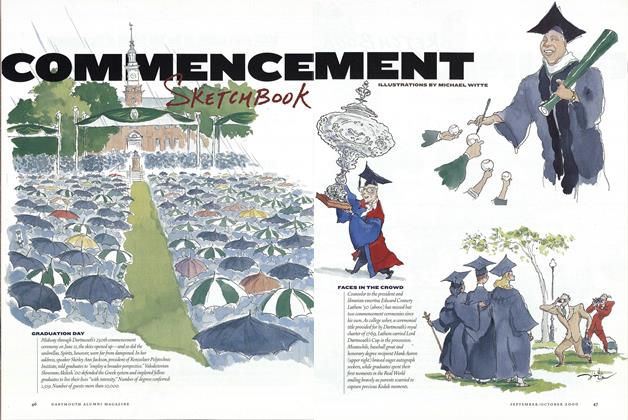

FeatureCommencement and Reunions: A Sketchbook

Sept/Oct 2000 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE DOCTOR FOR THE SPIRIT

JUNE 1990 By Elise Miller ’85 -

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

DECEMBER 1981 By Peter Bridges