A faculty researcher concludes that having a Dartmouth father has no correlation to performance in college

PROFESSOR OF CHILD PSYCHIATRY, DARTMOUTH MEDICAL SCHOOL

SHOULD father encourage his son to go to his college? Will it make it easier or will it be a burden for him to know that you had been there before him? Will you expect him to live out the unfulfilled aspirations of your own youth - to make the fraternity that didn't rush you; to achieve the grades you didn't get; to use those four years more wisely than you did at his age? Or does it make a difference for him that you were successful and graduated, with honors; that you were captain of the hockey team or were voted the man most likely to succeed?

These were some of the questions which prompted this study.

Like all researchers, I began with a hunch. It was based upon impressions gleaned from staff conferences, consultations to the Dean's Office, and from my clinical work at Dick's House. It went something like this: "The sons of alumni will function significantly better or significantly worse at Dartmouth than a comparable group of students whose fathers went to other colleges or whose fathers never attended college at all."

My hypothesis was based on the assumption that the college years are a critical period during which the young person makes his commitment to adulthood and that going to college occurs at a point in time when parental influences are of the utmost importance. I felt that the young man who attends his father's college receives a legacy (called just that by many admissions offices) which makes a difference in his life and personality development and in the way he perceives and experiences his college years. I saw parental expectations as very much related to this situation. If they had been appropriate and in the service of the son's needs up to the time of college choice, the legacy should encourage the son's positive identification with his father and should enhance mature growth.

On the other hand, if the expectations of the parents were inappropriate and not in the service of the son's needs, nonadaptive behavior on the part of the adolescent or young adult could be expected, most likely in the form of excessive dependency or rebelliousness. Since the alumnus' son is subjected to additional pressures and pulls from his parents, I thought his situation might shed light on a series of parent-child interactions revolving around the major issues of late adolescence and early adulthood. These involve the conflicts over dependency and independence, conformity and rebellion, growth and restriction of the self, and positive identification or repudiation of one's father.

With these concepts in mind I set about experimentally validating these impressions, assisted by the Dean of Freshmen, Albert I. Dickerson '30, and the Director of Admissions, Edward T. Chamberlain '36. Without their help this investigation would never have gotten off the ground. We began by making an informal survey of fifteen residential colleges and learned that approximately 15 percent of the matriculated students were sons of alumni. Although State universities do not keep track of these statistics, it appears that alumni sons constitute a sizable percentage of the nation's college student population and it is to be expected that their numbers will increase both as result of the college explosion of recent years and because of the tendency of college graduates to send their children on to higher education. As far as we were concerned, they were an important group to study.

Being an alumnus' son has been cited as the cause of a variety of difficulties ranging from anti-social behavior to scholastic "under-achievement." This belief is best observed during college administration meetings where all sorts of deviant behavior are explained on the basis of the student's being the son of an "old grad." Since colleges are constantly under pressure to take the sons of their alumni and to give them preference,, I felt it was worth while to attempt to subject these explanations (and excuses) to scientific scrutiny. Such an analysis is of considerable relevance to admissions policy. Obviously, colleges are dependent upon alumni for support in a variety of ways and Dartmouth is no exception. Alumni are called upon to recruit students of higher caliber; to donate their own money to the college as well as to solicit from others; even to recruit faculty in order to raise standards and maintain scholarly excellence. Alumni are important, influential and powerful. They are emotionally linked with Alma Mater through sentimental traditions, reunions, convocations, alumni clubs and associations ... a multitude of ties, and thus, when the son of an alumnus seeks admission to his father's college, his admission or refusal has different consequences for the college than in the case of other candidates. In some colleges, the chances of his admission may be determined by the degree to which he is "related" to the institution. Most colleges will give preference to the son of an alumnus when all other things are equal - and in some instances, when some other things are unequal.

There is a body of thought among some Ivy League alumni which illustrates the psychological and emotional issues involved. Briefly, it says that every son should have the opportunity to flunk out of his father's college. It is exemplified by the case of the Princeton alumnus who stated publicly that he didn't care if his son stayed at Princeton only one week, so long as the boy could join the Princeton Club of New York! With this background in mind, I began a survey of the literature only to find that there were no published studies on the children of alumni. A canvass of deans and admissions officers in comparable colleges confirmed this fruitless search. They suggested that anything connected with alumni was bound to be a sensitive topic. There were also hints of "suppressed" studies but, as will be seen later, I suspect this rumor was more in the service of perpetuation of a myth than it was a reflection of the facts.

THE next step was to draw a sample and three groups of students were randomly selected from the 9,191 Dartmouth students who matriculated during the years 1954 to 1965. These were:

1. Dartmouth alumni sons: 1,361 cases of whom 100 were randomly selected.

2. College sons: sons of alumni of other colleges. 4,550 cases of whom 100 were selected at random on the basis of having College Board scores identical to those of the Dartmouth sons. Both verbal and mathematical scores were matched.

3. Non-college sons: sons of fathers who never attended college; 2,330 cases of whom 100 were matched and selected in the same manner as the college sons. Information regarding these three groups was entered on a college performance and behavior chart developed for the study. The data were pulled from five major sources: the Dean's archives, financial aid office, admissions office, health service, and the alumni office. The three groups of students were compared on the following criteria:

Birthplace - Alumni sons tend to be from the Northeast as compared with college sons and non-college sons. None was born on the West Coast. There were 25 percent fewer college sons from the Northeast, which may be explained on the basis of competition from other colleges.

Home town - A preponderance of alumni sons come from the Northeast. However, a small number, 3 percent, now come from the West Coast. More alumni sons tend to come from towns of ten to fifty thousand population, whereas more non-college sons tend to come from rural districts.

Age — No significant differences were observed.

Father's college - Using Lovejoy's Guide to Colleges as an evaluating device, we find that the fathers of college sons tend to come from the most selective and highly selective colleges. Fifty-four percent were in these two categories.

Father's occupation - As would be expected, the fathers of alumni sons and college sons come mainly from the uppermiddle and upper classes.

Mother's college - Here again, the mother's college reflects class status, there being little difference between the alumni sons and the college sons. However, there is a large difference between these and the mothers of non-college sons in that 80 percent of the latter did not attend college.

Marital status of parents - Little or no difference was observed. Ninety percent of all three groups came from intact homes.

Health on admission — No differences were observed in any of the three groups. All were physically and mentally healthy on admission. None of the students gave a history of psychiatric treatment prior to admission to Dartmouth.

Dartmouth relatives - The total number of Dartmouth relatives for the 100 alumni sons was 167; for college sons it was 13, and for non-college sons, 6. The close ties that alumni sons had to Dartmouth are illustrated by the fact that almost 50 percent of alumni sons applied before the 11th grade, whereas only 5 percent of the college sons and non-college sons applied before this time.

Coeducational secondary schools - Fewer alumni sons attended coeducational secondary schools, 57 percent as compared with 81 and 86 percent of college sons and non-college sons, respectively.

Scholastic rating of secondary school - Rating the secondary school on the basis of admissions office criteria, we found that more alumni sons tended to come from excellent schools than did those from the other two groups. Fewer alumni sons came from average secondary schools. Eighty-five percent of the non-college sons tended to come from average or below-average schools. The connection with socio-economic status can be surmised.

Rank in class in secondary schools - More non-college sons were in the upper ranks of their secondary school class than college sons or alumni sons. Conversely, more alumni sons were in the lower half of their class. Seventy percent of the noncollege sons were in the upper ten percent of their class as compared to about 45 percent of both controls. Twenty-two percent of the alumni sons were in the bottom half of their class as compared to 10 percent of the college sons, and 3 percent of the non-college sons. It is clear from these data that alumni sons are given a certain amount of preference on admissions; that is, some are accepted with lower class rank. However, this may be accounted for in part by their attending more competitive schools.

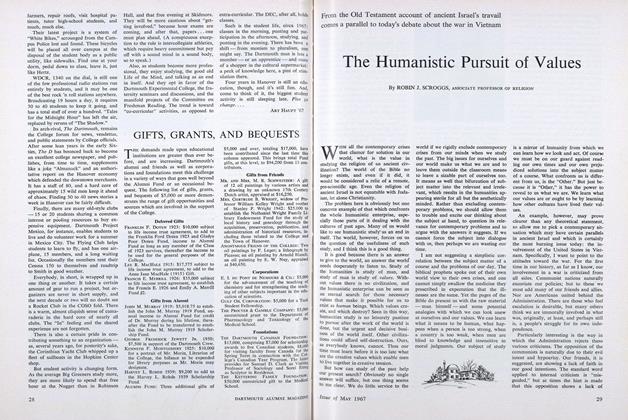

College Board scores - Figures 1 and 2 present the distribution of CEEB scores for Dartmouth. It is apparent that alumni sons do not differ as far as their mathematics scores are concerned but do show a slight tendency to perform less well on the verbal part of the examination.

Work and employment in secondaryschool - No difference was observed in the amount of summer and outside work engaged in by the three groups. There was a tendency for the non-college sons to have more outside work during the year and for them to have jobs of greater responsibility during the summer. Alumni sons tended to have fewer and less responsible jobs than college sons.

Extracurricular activities in secondaryschool - There were no differences in the number of extracurricular activities which were school connected. Extracurricular activities of the alumni sons tended to be of somewhat less responsibility, but probably of no statistical significance. Viewing those extracurricular activities which were not school connected, the alumni sons tended to have fewer whereas the non-college sons tended to have activities with slightly more responsibility.

Academic honors in secondary school - Alumni sons tended to have fewer academic honors in secondary school, 46 percent as compared to 62 percent of the control groups.

Vocational preferences at the time ofadmissions - It is difficult to determine the meaning of these data. Alumni sons appeared to be more undecided so far as vocational preference was concerned. Non-college sons were more interested in engineering and college sons in medicine.

We now proceed to data regarding college behavior and adjustment.

Economic - Financial aid is received by 50 percent of the non-college sons as opposed to 15 percent of the other two groups.

Academic factors - Alumni sons tend to do slightly less well on comprehensive examinations and tend to have a lower grade point average.

Completion of degree requirements There are no differences between the three groups. Approximately 80 percent complete the requirements for the degree.

Courses failed, probation and suspension - No differences emerge so far as the three groups are concerned, despite the tendency of some alumni sons to enter with somewhat lower academic standings. Although they tend to do generally less well than the controls, it is clear that this makes no difference so far as the passfail criterion is concerned. In other words, the admissions office is not accepting alumni sons who cannot "cut the mustard"!

Academic awards and citations - Moving to the other end of the spectrum, we find little difference among the three groups. Alumni sons and their controls receive approximately the same number of citations and awards for academic success during the four years. The same number in each group, 12 percent, graduate with distinction or honors.

Conduct in college - There is a general impression that the sons of alumni tend to get into more difficulties in college than do other students. I, too, had this impression, but the data does not bear it out. No differences whatsoever were noted in the number of penalties for conduct for each of the three groups. The number of warnings, probations, and suspensions for conduct were evenly distributed.

Drop-outs - No significant differences were noted in the three groups so far as dropping out and returning were concerned. Nine percent of the alumni sons did this as compared to 6 percent of the college sons and 10 percent of the noncollege sons. However, if we compare the three groups on drop-out and non-return, a small difference between the alumni sons and the college sons on the one hand and the non-college sons is noted. Nine

percent of alumni sons drop out and do not return. Thirteen percent of the college sons drop out and do not return, whereas only 5 percent of the non-college group who drop out do not return and go on for the degree. It may be that they return to a school other than Dartmouth.

Student activities - There is a slight tendency for alumni sons to belong to more organizations than the controls but no differences were observed in the kind of offices held in these organizations or in the responsibilities attached to them. No differences were observed in fraternity

membership, three-quarters of each group having joined a fraternity. As far as college employment is concerned, the non-college sons showed a far larger number who had jobs (40 percent) as contrasted to 7 percent of the alumni and college sons, once more reflecting socio-economic status.

If we consider sports activities, we find that alumni sons tend more often to be members of varsity teams and to engage in two or more sports as contrasted to their controls. However, there were no differences in the three groups as to the number of varsity letters received per student.

College major — No definite pattern emerges. More alumni sons tend to go on to the graduate business school of Dartmouth.

Health in college - No differences are evident in the three groups as measured by the number of visits to the student health service or by the number of days of hospitalization. There was some tendency on the part of alumni sons to use the psychiatric services more frequently than did the controls (15 percent, as compared to 9 percent of the controls).

SUMMARY

When evenly matched for ability by their College Board scores, the following differences emerged:

1. Socio-economic status factors

(a) The majority of college and alumni sons come from upper-middle and upper class families as determined by parental occupation, whereas the minority of non-college sons come from these groups.

(b) More college and alumni sons come from private secondary schools.

2. Differences in academic performance

(a) More alumni sons tend to be in the lower half of their class in secondary school than the controls. Fewer achieve academic honors in preparatory school.

(b) At Dartmouth, alumni sons tend to have a lower grade point average, to do less well on comprehensive examinations, and to end up more often in the lower ranks of their class.

3. Differences in conduct and activities

(a) Little differences emerged except for the tendency of alumni sons to "make" more teams than their controls. However, once they had achieved this, there were no differences in performance as measured by the number of awards received for athletic prowess.

(b) Lastly, there was a slight tendency on the part of alumni sons to make greater use of the psychiatric facilities.

CONCLUSIONS

At this stage of data collection and analysis, my original hypothesis that the sons of alumni would do significantly better or worse than the controls is not borne out. If anything, alumni sons tend to do as well as their academic potential would indicate and to do equally well on all the other criteria so far. I plan to gather more data through the use of a questionnaire which will be answered by the students involved and by their fathers as well. This may shed some light on post-academic adjustment and give us a clue to their later life adjustment. It is possible that the original hypothesis may be valid for a later period of time.

The major conclusion that one can draw from the data so far is that being an alumnus' son at Dartmouth is not correlated with any particular behavioral deviations or academic difficulties. I feel that I have at least scotched the myth which explains the student's failure to live up to expectations on the basis that "his father was an alumnus."

Figure 1. Range of CEEB score.

Figure 2. Range of CEEB score.

THIS STUDY was supported by a General Research Support Grant from the Dartmouth Medical School.

THE AUTHOR: Dr. Raymond Sobel is Professor of Child Psychiatry at the Dartmouth Medical School and also Assistant Medical Director for the College Health Service. Following graduation from Harvard in 1937 he took his M.D. degree at New York University and was a clinical psychiatrist in New York City for some years. From 1953 to 1960 he was Assistant Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Columbia University and Attending Psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, after which he spent four years, 1960-64, at the University of Washington School of Medicine as Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics. Dr. Sobel came to Dartmouth in 1964. With a $75,000 grant from the U. S. Public Health Service, he and Prof. Bernard E. Segal '55 of Dartmouth are now engaged in a four-year study of "Accidental Poisoning in Childhood," a continuation of research in which Dr. Sobel was previously engaged. He has found that psychological and social factors, as well as innocence, enter into the "accidental" poisoning of children.

Features

-

Feature

Feature75 Years of Helping Students

APRIL 1971 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement '89

June 1989 -

Cover Story

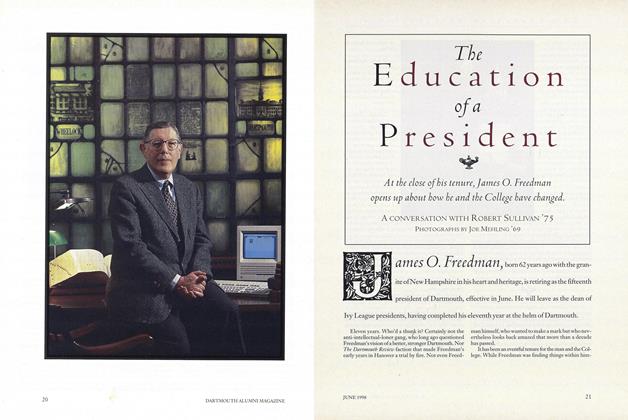

Cover StoryThe Education of a President

JUNE 1998 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFLUDE MEDAL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Started Writing Muscular Prose

OCTOBER 1989 By Chuck Young '88 -

Feature

FeatureHope

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Jim Hardigg '44