OMAN SINCE 1856, DISRUPTIVE MODERNIZATION IN A TRADITIONAL ARAB SOCIETY.

DECEMBER 1967 CHRISTIAN P. POTHOLM IIOMAN SINCE 1856, DISRUPTIVE MODERNIZATION IN A TRADITIONAL ARAB SOCIETY. CHRISTIAN P. POTHOLM II DECEMBER 1967

By Prof. Robert Geran Landen (History). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967. 488 pp. $12.50.

Robert Landen's book is a thorough, scholarly account of the history of the citystate Masqat and its hinterland, Oman. Sur- rounded by the sea on three sides and by the Empty Quarter of the Arabian peninsula on the fourth, this England-sized area long played an important role in the politics of India, East Africa, and the Middle East. Its "Silver Age" in the 18th century was due to its commercial and strategic position astride many important trade routes: Red Sea-Suez, Trans Iranian, Central Asian, Indian and East African. When the lucrative trade of these areas lured more powerful states, Oman fell into a period of decline, emerging only with major discoveries of oil in 1963.

One interesting aspect of Oman's history is the attempt of the various sultans to stave off ruin. In 1832 for example, Sayyid Safid ibn-Sultan transplanted his dynastic capital from Oman to Zanzibar off the coast of East Africa. The Zanzibar branch of the dynasty remained an important factor in East African politics until an African revolution in 1964 ended its political causal efficacy, fully a century after the decline of Oman proper.

Landen's account of this small, little known country is well documented and clearly written. He is successful in integrating the internal history of Oman with the larger external framework of British policy toward India, Russian designs on Iran, and French interest in the Indian Ocean. The persistent competition between rulers and would-be rulers, the collision of modernity and tradition, the clash of imperial powers, all are sketched with precision. What Landen has done is to make of Oman a microcosm of the entire colonial pattern and the revolutionary impact of what he calls the "western presence."

At the same time, one may have difficulty with his major premise: "Oman's sudden fall to utter political insignificance and economic stagnation remains a particularly striking example of just how destructive the process of modernization has been in some societies." The intrusion of modernity was no doubt disruptive (I am uneasy, however, about Landen's persistent equation of physical inputs such as telegraphs and steamers with "modernization"), but the decline of Oman seems to have been due more to a changed power relationship within the Persian Gulf. As long as Oman's chief competition in the area were the city states such as Qays and Hormuz, her position was more or less secure. Likewise, even when the competition became "modern" in the form of Portugal during the 16th century, Oman was able to hold her own because of Portugal's size. The arrival of Great Britain and France, however, upset the situation. Once these major powers decided to intervene, the 500,000 Omanis could do very little indeed. Power, not modernity, submerged Oman.

Landen himself hints at this relationship when he rightly points out that the political decline of Oman coincided with the British residency in Oman of Lewis Pelly and increased British interest in the Persian Gulf. Pelly's residency from 1862-1872 was marked by widespread British activity in the area and, on a broader canvas, presaged a major shift in British Colonial policy - from minimum to maximum involvement in the non European world. Once begun, this trend proved nearly irreversible, at least until after World War II.

As Assistant Professor of Government atDartmouth, Mr. Potholm with Prof. CharlesB. McLane teaches a course in the Politicsof West Africa, and, alone, an advancedseminar in Political Development.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

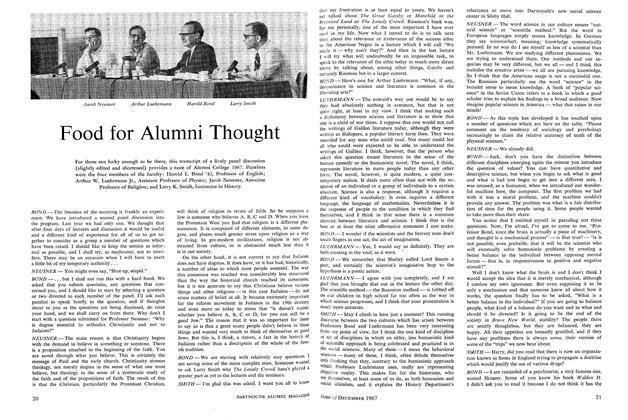

FeatureFood for Alumni Thought

December 1967 -

Feature

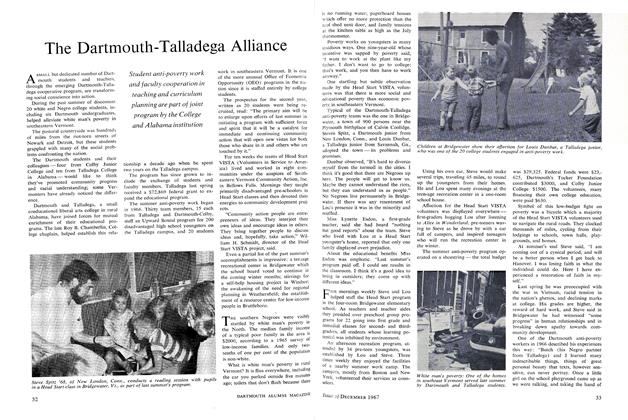

FeatureThe Dartmouth-Talladega Alliance

December 1967 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

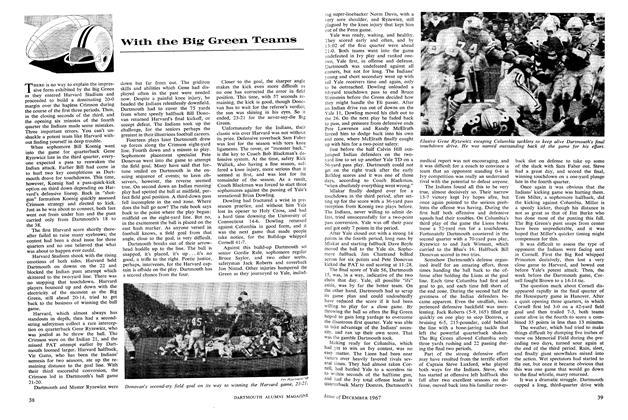

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1967 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1967 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

December 1967 By WALTER C. DODGE, DR. THEODORE R. MINER, TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

December 1967 By EARL H. COTTON, LOUIS A. YOUNG JR.

CHRISTIAN P. POTHOLM II

Books

-

Books

BooksDartmouth

November, 1922 By C.C.S. -

Books

BooksPROBLEMS OF AMERICAN DEMOCRACY

January 1941 By Everett W. Goodhue '00 -

Books

BooksDEVELOPED LESSONS IN PSYCHOLOGY.

FEBRUARY 1930 By Gordon W. Allport -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN ENGLAND,

April 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22. -

Books

BooksTRADE-UNION POLICIES IN THE MASSACHUSETTS SHOE INDUSTRY

April 1933 By Herman Feldman -

Books

BooksHELIX,

October 1947 By Sidney Cox