Student anti-poverty work and faculty cooperation in teaching and curriculum planning are part of joint program by the College and Alabama institution

A SMALL but dedicated number of Dartmouth students and teachers, through the emerging Dartmouth-Talla-dega cooperative program, are transforming social conscience into action.

During the past summer of discontent 20 white and Negro college students, including six Dartmouth undergraduates, helped alleviate white man's poverty in southeastern Vermont.

The pastoral countryside was hundreds of miles from the riot-torn streets of Newark and Detroit, but these students grappled with many of the social problems confronting the nation.

The Dartmouth students and their colleagues - four from Colby Junior College and ten from Talladega College in Alabama - would like to think they've promoted community progress and racial understanding; some Vermonters have already noticed the difference.

Dartmouth and Talladega, a small coeducational liberal arts college in rural Alabama, have joined forces for mutual enrichment of their educational programs. The late Roy B. Chamberlin, College chaplain, helped establish this relationship a decade ago when he spent two years on the Talladega campus.

The program has since grown to include the exchange of students and faculty members. Talladega last spring received a $72,869 federal grant to expand the educational program.

The summer anti-poverty work began in 1966. Thirty team members, 15 each from Talladega and Dartmouth-Colby, staff an Upward Bound program for 200 disadvantaged high school youngsters on the Talladega campus, and 20 students work in southeastern Vermont. It is one of the more unusual Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) programs in the nation since it is staffed entirely by college students.

The prospectus for the second year, written as 20 students were being recruited, read: "The primary aim will be to enlarge upon efforts of last summer in initiating a program with sufficient force and spirit that it will be a catalyst for immediate and continuing community action that will open new vistas for both those who share in it and others who are touched by it."

For ten weeks the teams of Head Start VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) lived and worked in eight communities under the auspices of Southeastern Vermont Community Action, Inc. in Bellows Falls. Mornings they taught primarily disadvantaged pre-schoolers in Head Start classes and then devoted their energies to community development projects.

"Community action people are entrepreneurs of ideas. They interject their own ideas and encourage ideas in others. They bring together people to discuss ideas and, hopefully, take action," William H. Schmidt, director of the Head Start VISTA project, said.

Even a partial list of the past summer's accomplishments is impressive: a teenage recreational center in Bridgewater which the school board voted to continue in the coming winter months; stirrings for a self-help housing project in Windsor; the awakening of the need for regional planning in Weathersfield; the establishment of a resource center for low-income people in Brattleboro.

THE southern Negroes were visibly startled by white man's poverty in the North. The median family income of a typical poor family in the area is $2000, according to a 1965 survey of low-income families. And only two-tenths of one per cent of the population is non-white.

What is white man's poverty in rural Vermont? It is flies everywhere, including the car you parked outside five minutes ago; toilets that don't flush because there is no running water; paperboard houses which offer no more protection than the tool shed next door, and family tensions at the kitchen table as high as the July thermometer.

Poverty works on youngsters in many insidious ways. One nine-year-old whose incentive was sapped by poverty said, "I want to work at the plant like my father. I don't want to go to college; that's work, and you then have to work anyway."

One startling but subtle observation made by the Head Start VISTA volunteers was that there is more social and educational poverty than economic poverty in southeastern Vermont.

Typical of the Dartmouth-Talladega anti-poverty teams was the one in Bridgewater, a town of 900 persons near the Plymouth birthplace of Calvin Coolidge. Steven Spitz, a Dartmouth junior from New London, Conn., and Louis Dunbar, a Talladega junior from Savannah, Ga., adopted the town - its problems and promises.

Dunbar observed, "It's hard to divorce myself from the turmoil in the cities. I think it's good that there are Negroes up here. The people will get to know us. Maybe they cannot understand the riots, but they can understand us as people." No Negroes live permanently in Bridgewater. If there was any resentment of Lou's presence it was in the minority and muffled.

Miss Lynette Esdon, a first-grade teacher, said she had heard "nothing but good reports" about the team. Steve who lived with Lou at a Head Start youngster's home, reported that only one family displayed overt prejudice.

About the educational benefits Miss Esdon was emphatic. "Last summer's program paid off. I could see results in the classroom. I think it's a good idea to bring in outsiders; they come up with different ideas."

FIVE mornings weekly Steve and Lou helped staff the Head Start program in the four-room Bridgewater elementary school. As teachers and teacher aides they presided over preschool group programs for 22 going into first grade and remedial classes for second. and third-graders, all students whose learning potential was inhibited by environment.

An afternoon recreation program, attended by 34 pre-teen youngsters, was established by Lou and Steve. Three times weekly they enjoyed the facilities of a nearby summer work camp. The campers, mostly from Boston and New York, volunteered their services as counselors.

Using his own car, Steve would make several trips, traveling 45 miles, to round up the youngsters from their homes. He and Lou spent many evenings at the teen-age recreation center in a one-room school house.

Affection for the Head Start VISTA volunteers was displayed everywhere first-graders hugging Lou after listening to Alice in Wonderland, pre-teeners waving to Steve as he drove by with a car full of campers, and inspired teenagers who will run the recreation center in the winter.

The summer anti-poverty program operated on a shoestring - the total budget was $29,325. Federal funds were $23,625, Dartmouth's Tucker Foundation contributed $3000, and Colby Junior College $1500. The volunteers, many financing their own college education, were paid $630.

Symbol of this low-budget fight on poverty was a bicycle which a majority of the Head Start VISTA volunteers used to navigate the rural roads. They clocked thousands of miles, cycling from their lodgings to schools, town halls, playgrounds, and homes.

At summer's end Steve said, "I am coming out of a cynical period, and will be a better person when I get back to Hanover. I was losing faith in what the individual could do. Here I have experienced a restoration of faith in myself."

Last spring he was preoccupied with the war in Vietnam, racial tension in the nation's ghettos, and declining marks at college. His grades are higher, the reward of hard work, and Steve said in Bridgewater he had witnessed "some progress" in human relationships and in breaking down apathy towards community development.

One of the Dartmouth anti-poverty workers in 1966 described his experiences this way: "Butch (his Negro partner from Talladega) and I learned many indescribable things, things of great personal beauty that texts, however sensitive, can never portray. Once a little girl on the school playground came up as we were talking, and taking the hand of each of us said, 'Gee, I wish I were your sister. It must be fun where you live.' It was fun, that summer, and it needn't be lost."

WHAT can Dartmouth, a prestigious Ivy League college, gain from Talladega, a struggling Negro college in the Deep South? Dartmouth thinks both the College and its students have much to gain spiritually and materially.

Dean Charles F. Dey '52 of the Tucker Foundation said, "Education is too self-centered. Dartmouth should not be a cocoon for four years. If we are to justify our existence, the undergraduate must be confronted with the realities of human misery, hopelessness, and the unfinished business of our society.

"We cannot defend bringing 3000 relatively affluent young men to Hanover for four years unless we take seriously their potential for improving the human condition. Dartmouth will be successful only as its graduates leave here determined to make a difference by applying their talents to the desperate needs of the world."

But Dartmouth can gain more than the spiritual intangibles resulting from involvement with the cross-currents of contemporary social problems. The scope of its educational program will be broadened by contact with Talladega College.

A faculty steering committee headed by Prof. Herbert W. Hill recently observed, "We believe also that the benefits of this kind of relationship are reciprocal and that Talladega has much to offer Dartmouth. For example, we hope to utilize Talladega faculty strength in areas such as Negro history, literature, and art."

Similarly, Talladega does not want to be "a weak sister" in the partnership. G. Herbert Gessert, director of planning at Talladega, said, "Faculty strengthening and curriculum development are our main objectives in this cooperative program. We also hope that Dartmouth College faculty and students might gain something from their contact with a predominantly Negro college set in the midst of the Deep South."

Quite naturally the Tucker Foundation is the focal point for the Dartmouth-Talladega cooperative project. William Jewett Tucker, the College's last preacher president, warned students who wanted to make their imprint on the world that intellectual prowess must be combined with an equal amount of conscience and heart.

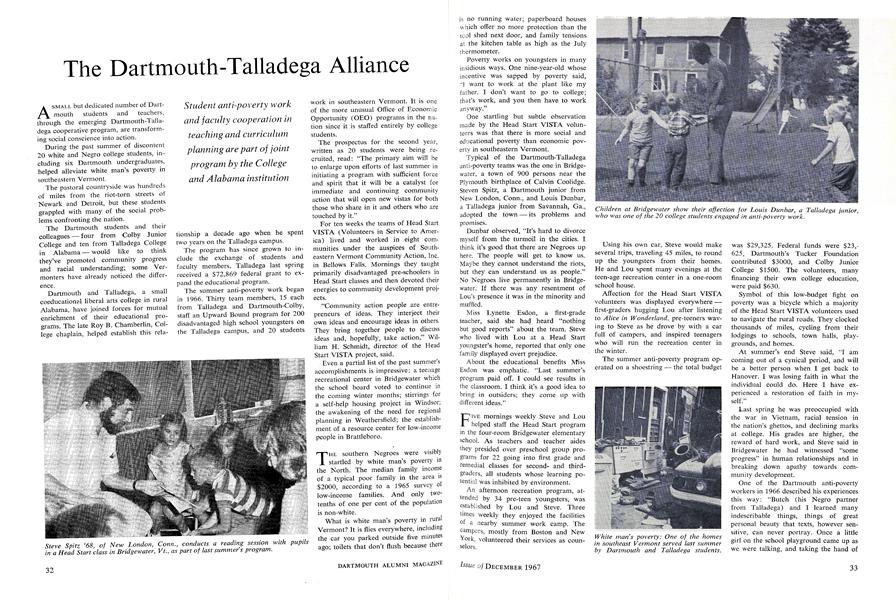

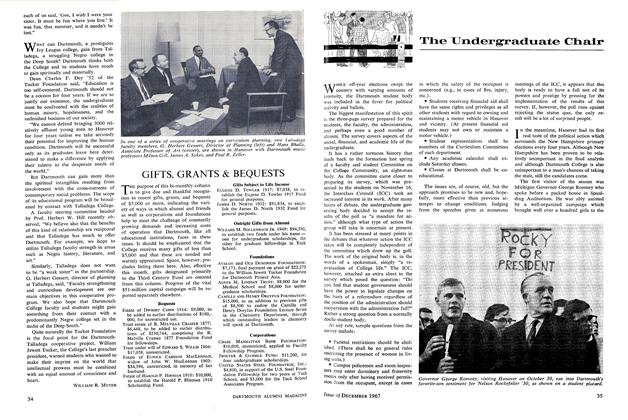

Steve Spitz '68, of New London, Conn., conducts a reading session with pupilsin a Head Start 'class in Bridgewater, Vt., as part of last summer's program.

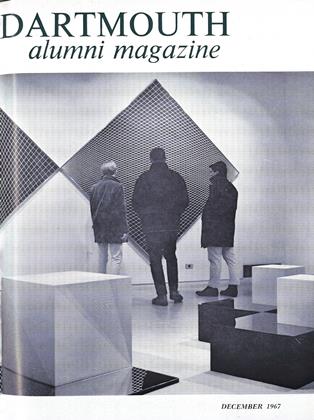

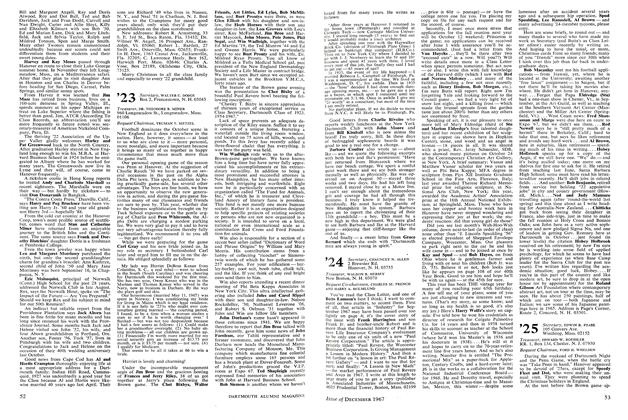

Children at Bridgewater show their affection for Louis Dunbar, a Talladega junior,who was one of the 20 college students engaged in anti-poverty work.

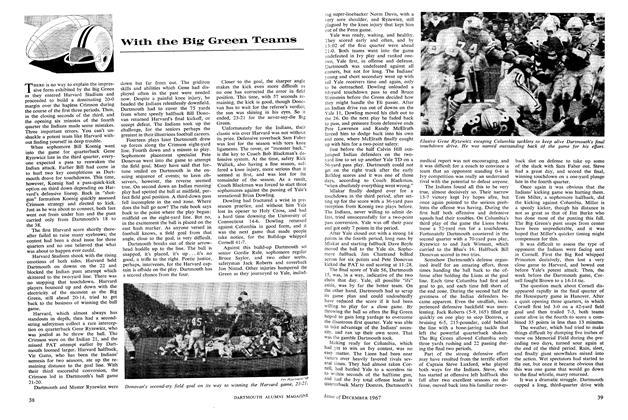

White man's poverty: One of the homesin southeast Vermont served last summerby Dartmouth and Talladega students.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFood for Alumni Thought

December 1967 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1967 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1967 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

December 1967 By WALTER C. DODGE, DR. THEODORE R. MINER, TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

December 1967 By EARL H. COTTON, LOUIS A. YOUNG JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

December 1967 By CHAUNCEY N. ALLEN, WALDON B. HERSEY, CHARLES M. FRENCH1 more ...

WILLIAM R. MEYER

-

Article

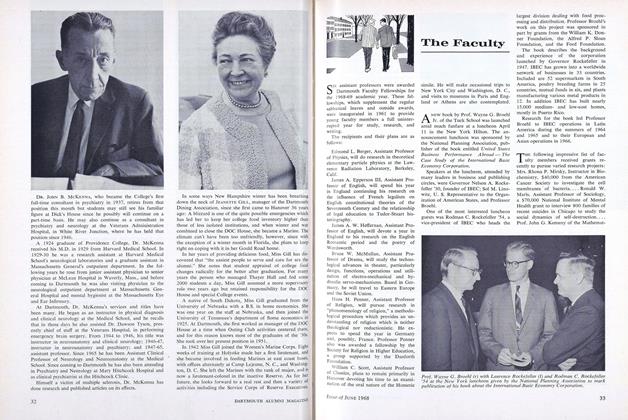

ArticleThe Faculty

FEBRUARY 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

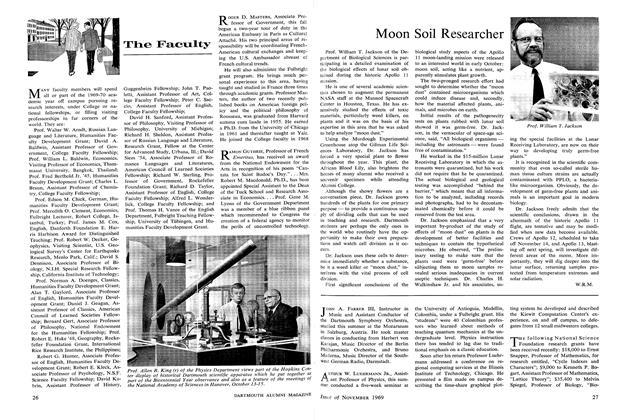

ArticleThe Faculty

JUNE 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

NOVEMBER 1969 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleFaculty

OCTOBER 1970 By William R. Meyer -

Article

ArticleFaculty

NOVEMBER 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleFaculty

DECEMBER 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER

Features

-

Cover Story

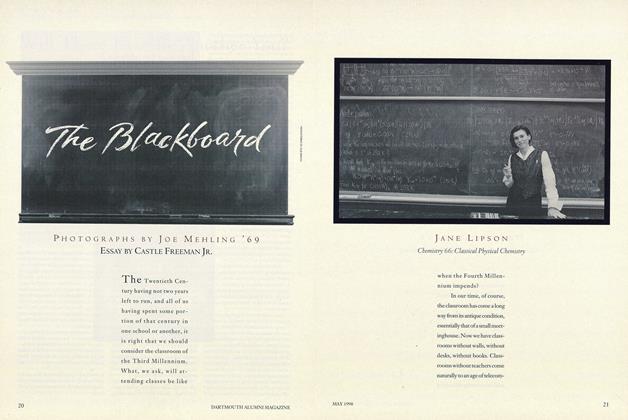

Cover StoryThe Blackboard

May 1998 By Castle Freeman Jr. -

Feature

Feature'... A whole pool of frustration, anger, resentment...'

February 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

Feature"Intensive" Is the Word for It

MARCH 1968 By Joan Hier -

Feature

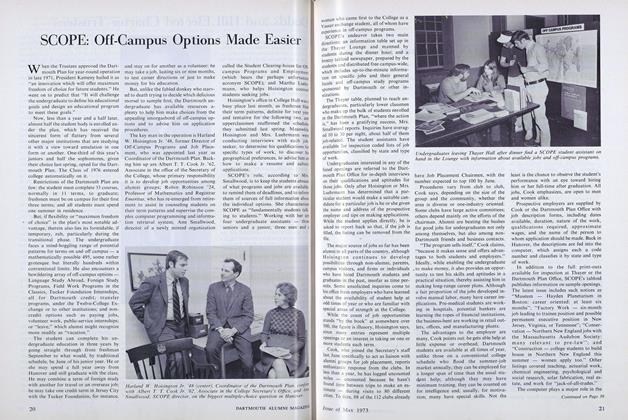

FeatureSCOPE: Off-Campus Options Made Easier

MAY 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

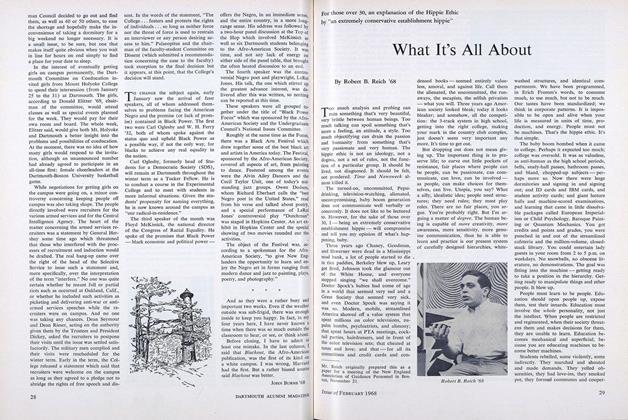

FeatureWhat It's All About

FEBRUARY 1968 By Robert B. Reich '68 -

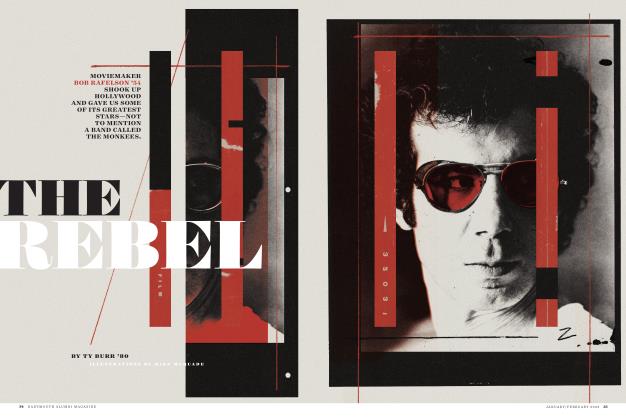

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Rebel

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2023 By TY BURR '80