by Francis Steegmuller '27. Random House,1949. 430 pages.

In this readable and scholarly biography, Francis Steegmuller seems to have set himself two goals: to rehabilitate Maupassant as "a considerably more imposing figure in the literary path than many critics since James have been inclined to admit," and to make him more approachable by revealing "the touch of softness, the human flaw" that Henry James tried in vain to find in him. In these days when there is a tendency to consider a liking for Maupassant about on par with a taste for sparkling burgundy and Abbot & Costello, this is an heroic undertaking.

Mr. Steegmuller's sympathetic appraisal of Maupassant as a man and as an artist never blinds him to his subject's shortcomings. At his best, Guy de Maupassant was the "true poet" that Croce pronounced him to be and the "wonderfully rare" artist that Henry James recognized in him. At his worst, he was a venal purveyor of cheap sensationalism and vulgarity. The only excuse for stories like La Fenetre and Un Sage is that they paid off, as Mr. Steegmuller points out, richly enough to afford their author the leisure and freedom that he needed to create those pure masterpieces that were at once the wonder and despair of Chelcov.

Mr. Steegmuller's handling of Maupassant's personal life complements the picture of Maupassant the convivial rake with a convincing portrait of a tortured soul whose anguish and revulsion were more frequent and profound than his flashes of gay cynicism.

In one of the appendices of the book, the author renders a real service to Maupassant's reputation by warning American readers against the spurious trash that is often foisted off on the public as "genuine, complete, UNEXPURGATED" translations of Maupassant, and by listing as fakes no less than sixty-five stories currently published in such collections.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleBack to Hanover in December

February 1950 By WILLIAM H. HAM '97 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

February 1950 By ROYAL PARKINSON, GILBERT H. FALL, FLETCHER A. HATCH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

February 1950 By ELMER G. STEVENS JR., STANTON B. PRIDDY, THEODORE R. HOPPER -

Article

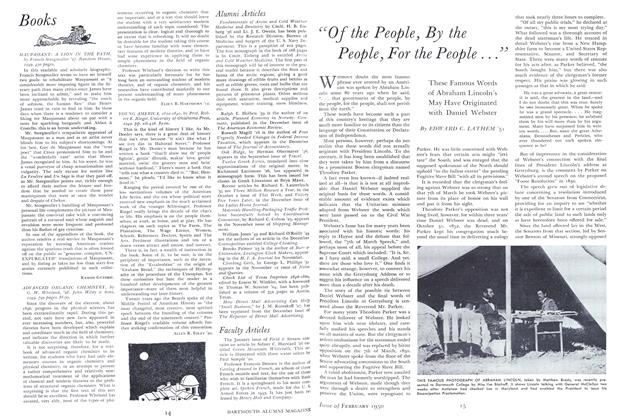

Article"Of the People, By the People, For the People..."

February 1950 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

February 1950 By NORBERT HOFMAN JR., JOHN E. MORRISON JR., ROBERT L. PATERSON

Ramon Guthrie

-

Books

BooksLEARNING TO FLY FOR THE NAVY

OCTOBER 1931 By Ramon Guthrie -

Books

BooksPRACTICAL FLIGHT TRAINING

November 1936 By Ramon Guthrie -

Books

BooksTHE SELECTED LETTERS OF GUST AVE FLAUBERT.

May 1954 By RAMON GUTHRIE -

Books

BooksThe Back of My Mind

DECEMBER 1966 By Ramon Guthrie -

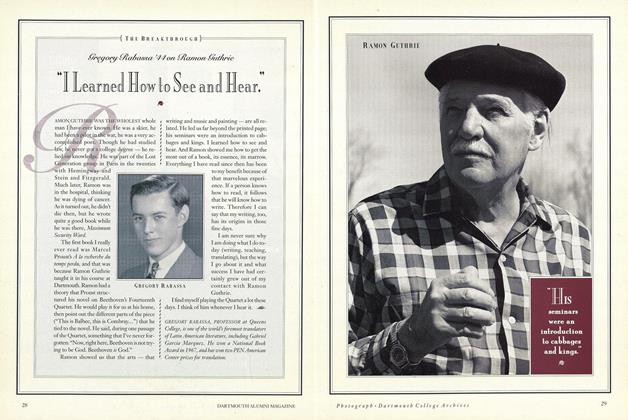

Feature

FeatureGregory Rabassa '44 on Ramon Guthrie

NOVEMBER 1991 By Ramon Guthrie

Books

-

Books

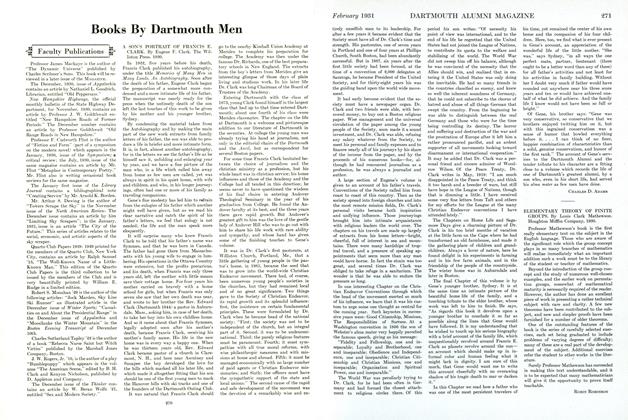

BooksFaculty Articles

March 1956 -

Books

BooksEL MUNDO MAGICO DE JOSE MARIA ARGUEDAS.

October 1974 By ARTURO MADRID -

Books

BooksCORTINA'S FRENCH IN 20 LESSONS.

October 1952 By Francois Denoeu -

Books

BooksINDEX TO TOP-HIT TUNES (1900-1950).

JANUARY 1963 By GENE MARKEY '18 -

Books

BooksMIGRATION FROM VERMONT (1776- 1860)

October 1937 By Richard F. Upton '35 -

Books

BooksELEMENTARY THEORY OP FINITE GROUPS.

February, 1931 By Robin Robinson