The undergraduate is in the dilemmaof working under a curriculum whichis growing more extensive (through theconstant division and subdivision ofsubject matter) and under instructorswho are growing more specialized intheir intellectual interests.

THIS statement would be accepted without much dissent on nearly every college and university campus today. It was made by Dartmouth's President William Jewett Tucker in an Atlantic Monthly article in 1911.

Although this early concern with new forces in higher education, expressed more than fifty years ago, helps to make the point that change has long been an inescapable ingredient in the life and work of any effective college - the liberal arts college especially it would be a mistake to try to apply the idea of "nothing new under the sun" to what has been happening to American higher education in these postwar years.

To begin with, the colleges and universities have moved from the periphery to the very center of modern life. The pressures upon them from all sides have transformed the old traditional, almost genteel, kind of educational change into a snowballing kind of change which is more drastic and rapid than anything that could have been conceived when Dr. Tucker was stating his concern back in 1911. Every area on the globe is now germane to higher education, politically and culturally. Social upheavals within the nation join with world events and scientific advances to give the colleges and universities new subject matter to bring within the modern curriculum. The vast improvement in secondary school preparation is having a tremendous effect on how the colleges handle their part of the educational job. This pressure from below is matched by another from above - the graduate schools, to which an increasingly higher percentage of college students now move on for another step in their formal education. tion.This preponderant choice of professional education rather than general education has its mate in the pressure toward specialization, inevitable result of the explosion in knowledge and spurred on by the new breed of faculty now teamed up with the new breed of student. Among other things accelerating change in the colleges are federal and foundation grants in the millions of dollars, making possible educational innovations and experiments that institutions could never have undertaken by themselves.

As a college determined to stay in the forefront of American higher education, Dartmouth has been responsive to all these pressures of the modern world, but not necessarily in the way that the giant universities, concentrating on graduate work and yet handling skyrocketing undergraduate enrollments, have sought to be responsive. In Dartmouth's case, an additional and special incentive to change has come from the reexamination of the entire institution involved in the Trustees Planning Committee program undertaken as a prelude to the College's bicentennial in 1969. Indeed, in the past ten years Dartmouth has in some measure been experiencing a state of becoming rather than a state of being.

College Purpose in Today's World

In these shifting circumstances what does the College do about its sense of purpose? Does that change too, or does the historic aim of the liberal arts college, concerned with the intellectual and moral fulfillment of the individual as well as his professional competence, still have validity?

This was the very first question raised by the Trustees Planning Committee, and to President Dickey was given the primary responsibility for providing the answer.

From the past, according to President Dickey, today's College has inherited four elements of its ongoing purpose: (1) a sense of ultimate obligation to human society, (2) a commitment to the liberal arts as the best educational foundation for the fullest possible development of individual competence and conscience, (3) a commitment to the primacy of undergraduate education, and (4) the offering of graduate programs in such a way as to be integrated with the dominant purpose of Dartmouth as an undergraduate liberal arts college.

President Dickey finds the College's historic purpose both valid and adequate for meeting the changing needs of the society Dartmouth serves today. The responsiveness to this obligation takes new and fuller and more intensive forms, to be sure, as the central needs of society are redefined. On the national level President Dickey cites the growing need for men trained in the basic competencies on which today's industrial and scientific society is built, and also for men equipped to use and create the power of contemporary knowledge. On the level of human society generally, he singles out the overriding need to balance physical power with the moral and political control of that power.

Finally, President Dickey defines Dartmouth's purpose in terms of creating leadership - a responsibility that John W. Gardner, in his article in our February issue, found some segments of American higher education all too ready to abdicate in their drive to educate the technical expert. Wrote President Dickey in his TPC statement about purpose: "The liberal arts college, more than any other institution in American life, is directly concerned at the higher levels of education with the development in all of its products of both the will and the capacity to serve the public good regardless of how the individual makes his own living. If Dartmouth annually can put six hundred dredsuch public-minded, competent citizens back into the home communities of our [fifty] states during the next fifteen years, she may be able to make a truly decisive contribution to the perpetuation of the human heritage which all education holds in trust. That, at this point, should be her ennobling aim."

Degree Requirements

A liberal arts education involves a great deal more than passing the 36 courses and the comprehensive examination now required for Dartmouth's A.B. degree, and the reaffirmed purpose poseof the College is not fulfilled by any man in the short space of four undergraduate years. But college education must have the help of a formal structure such as a curriculum (discussed by Professor Hurd in a separate article in this issue) and a set of requirements for the degree.

The ideal of both breadth (general education) and depth (specialization) in undergraduate studies was adopted by Dartmouth in its celebrated curriculum revision of 1924-25. This is still basically in effect today, but there has been considerable postwar modification, as will be explained when this article turns to changes in the underclass and upperclass years. General education in some colleges takes the form of interdisciplinary survey courses or so-called core curriculums; in others, Dartmouth among them, it takes the form of a required distribution of courses in all three of the Divisions of the Humanities, the Sciences, and the Social Sciences.

At the present time the distribution requirement for the A.B. degree calls for four term courses in each of the three divisions, not counting English 1, language courses 1, 2, 3, or courses taken for ROTC. Since the war the humanities requirement has grown from two courses (besides English and language) to three courses in the curriculum revision of 1958, to four courses in last year's revision which made English 2 an elective.

In addition to English 1, a foreign language proficiency equivalent to three terms of college-level study in one foreign language, and the distribution courses, the Dartmouth degree requirements at present are a major program usually consisting of eight courses in one field of concentration, the Great Issues Course for seniors, and completion of the physical education requirement, usually met in the first two years.

With the adoption of the three-term, three-course program in 1958, the number of courses for the degree was reduced from 40 to 36 - three courses taken in each of the twelve terms instead of five courses taken in each of the eight semesters. Although the apparent effect of this was to reduce the number of free electives, the superior preparation of incoming students and the more liberal arrangements for wanting them English, language and distribution credits served to permit students to substitute other courses as free electives and thus offset the reduction.

But more important than any loss in the number of free electives, the "three three" plan permitted the student to go into each subject in greater depth (creating "breadth in depth" some claimed) and to have more time outside the classroom for independent, self-directed study. The dominant postwar swing away from dependence on classroom teaching to the student's own independent work under faculty guidance was given a big push with the curriculum changes adopted by the faculty in 1958.

The Key Word

Outside of the three-term, three-course plan, now in its seventh year, the formal educational structure just sketched gives little evidence of radical change in Dartmouth's academic program during these postwar years; the outlines of the structure are rather familiar to Dartmouth graduates going back to the thirties. The impression is misleading, however. Within the traditional framework a whole new "insides" exists, a whole new style of education prevails. The solid, built-in walls have given way to movable partitions. The academic atmosphere is different and the people working inside don't do things the way they used to, but then the things they are doing aren't the same either.

The one word that helps most to explain what is going on is flexibility. Except for variations in the choice of free electives and the major, and some give for the really bright student doing honors work, the undergraduate course in past years followed a pattern that had an incoming class meeting the same prescriptions at the same pace and in pretty much the same way. Progress through the four years was definitely spelled out, and the general idea was that the student should cut his cloth to the academic pattern the faculty had devised for him. Today there are multiple opportunities for the capable and serious student to work out an educational program that will more fully meet his individual needs and interests - and capable and serious students are at Dartmouth in large numbers.

There is flexibility in the level at which an incoming student begins his college work, in the way he meets his distribution requirements, in the year in which he begins his major study, in the projects he carries out in his more advanced courses. There is flexibility in the major program and in the topics of seminar courses within a given department, and more flexibility in the weekly course schedule for student and professor.

Breaking away from the old rigidities has been a response to the needs and expectations of the new breed of student, who comes to college bright enough and prepared enough to make possible the new procedures and advanced course content. In increasing numbers, also, students arrive knowing what they want to specialize in and are eager to get started. The extent to which the intellectual quality of the student body has improved can be seen in the jump of well over 100 points in the past decade in the average College Board scores of freshmen. The verbal score has climbed from 548 to 654, and the math score from 585 to 705. These are capable, serious students who want to make productive use of their time.

Today's more flexible and unregimented way of setting course content and handling classes, even at the introductory level, also comes from a young faculty, neck deep in scholarly work and not content to divorce their teaching from either the level or the spirit of this work.

The First Two Years

The freshman and sophomore years have long been a problem apart in college education, and it wasn't too long ago that getting over the "sophomore hurdle" marked for most students the beginning of serious scholastic work. The trend is definitely away from segregating the first two years as a period in which general education requirements are met, a variety of elementary courses are sampled in order to pick a major, and studies are, in effect, mere extensions of secondary school. The caliber of today's entering student, the sharp upgrading of precollege schooling, and the professional drive of the faculty all combine to force an entirely new approach to the academic work of the freshman and sophomore years.

Dartmouth for some years has offered placement in advanced courses to freshmen presenting evidence of college-level competence in certain subjects. College Board aptitude and achievement tests and the College's own proficiency examinations have been used to spot these qualified men. In more recent years Dartmouth has extended this recognition by freeing men of the distributive requirement in subjects in which they have had exceptional preparation, by granting them actual course credits toward the degree before or at the time of entrance, and, where credit for three or more courses has thus been earned, by giving them additional course credits which will advance their standing and accelerate completion of the undergraduate program. For example, the bright freshman who is given credit for five or more Dartmouth term courses spread over at least two subject fields, such as chemistry and mathematics, is credited with enough unspecified additional courses to make up the total of nine normally carried in the freshman year.

In the present freshman class, 34 men qualified for accelerated graduation. Since the plan was adopted, however, nearly all such men have rejected acceleration and have preferred to use the opportunity to enrich their education along the lines of their special interests. In the present freshman class, 198 proficiency exemptions were granted in the sciences, 184 in the social sciences, and 1279 in the humanities (753 of these in the Romance languages, 246 in German, 137 in English 1, 115 in Latin, and 28 in Russian).

Flexibility in the freshman-sophomore curriculum was increased still further last year when the faculty put into effect for the Class of 1969 changes that now permit the distributive requirement to be spread over four years instead of two, permit the election of a major at any time after the first term of freshman year, and require each man to elect a Freshman Seminar, patterned on the successful seminars in English 2.

The net effect of these changes, elevating the level of college work in the freshman and sophomore years and giving students a new latitude in moving ahead into study areas of special interest to them, is to blur the old dividing line between the two halves of Dartmouth's educational program and to give all four years a new cohesiveness and common quality of high-level work. There is greater intellectual challenge for a man at the start of his college course, and a taste of independent work now comes early in the required seminar. For the sophomore year there is special benefit in having its lackluster character eliminated.

As an interesting facet of the liberalized distribution rule, the student can if he chooses take all four courses in one subject to meet the requirement in a given division, so long as they are outside his major department. He can delay his social science courses, for example, and then take all four in history in such a way as to tie them in with his major. This provides distribution and greater concentration at the same time, and gives the student the chance to fashion a course of study, especially at the upperclass level, that is his own.

This year's enlarged program of Freshman Seminars has opened up the freshman year with more opportunity to have close association with faculty members, to participate in small group discussions on a selected topic, and to carry on independent study of the topic with written papers summarizing one's observations. Seminars in all departments will have the same emphasis on writing skill that the English 2 seminars have. For the current spring term, seminars are being given in Comparative Literature (Utopia and Reality), The Classics (Greek Mathematical Sciences), and History (Frontier Development in the Americas and Imperialism and Nationalism) in addition to a large number of English 2 seminars. Seminars were given earlier this year in Religion and Romance Languages, and next year Economics, Sociology, Philosophy, and Engineering Science will join the list.

Prof. Henry L. Terrie of the English Department, chairman of the Freshman Seminar program for the coming year, calls the new first-year courses "an imaginative new way to introduce a student to a discipline - much more exciting and challenging than the big introductory courses that used to be the only ones a freshman could take."

Honors sections for able freshmen in mathematics and psychology, varied introductory courses for those going on to advanced work in a department, and intensive beginning language courses (French and Spanish next year will have a pilot program of double courses) are other indications that the elementary nature of freshman year is becoming a thing of the past.

Dartmouth's remarkably capable students arrive with the ability and readiness to tackle this stepped-up program, the faculty is equally ready to pull them into the mainstream of serious academic work, and the College is happy with the new climate of the freshman and sophomore years, even though it knows it can be still better.

The Upperclass Years

In his foreword to The College onthe Hill, President Dickey wrote: "Today's Dartmouth student must not only be prepared for the adult life of an ongoing learner, but increasingly he must also be specifically prepared for going on as a student to the specialized work of graduate education. Modern knowledge in all walks of life, not merely as formerly only in the so-called learned professions, requires a professional level of competence in any man who aspires to live and work at the leadership levels of American society."

The fact that the great majority of Dartmouth graduates now go on to graduate school has been the biggest impetus for postwar change at the level of major study. A survey of the Class of 1964, made by Prof. Clark W. Horton, director of the Office of Tests and Educational Research, showed that 428 men or 68% of those graduating on time went directly to graduate school. Another 155 men or 23% went into military service, the Peace Corps or activities other than employment, and within this group many had plans to enter graduate school later. Well over 70% of each Dartmouth graduating class, probably 75% or more, can therefore be said to go on to advanced study after getting the A.B. degree. Professor Horton's study showed that 83% of the men majoring in science went directly to graduate or professional schools.

To meet the needs of these men the departments at Dartmouth have introduced more specialized work into the major and in some cases have redesirned their major programs along the lines of pre-professional training. It is at this level of undergraduate study that the proliferation of new knowledge, especially in the sciences, makes itself most strongly felt in course content and in the emphasis given to certain areas within the major field.

The fact that fairly advanced courses have moved down into the sophomore year is some help in reducing the pressure of what must now be covered if the major is to be more professional. Reexamination of what the major has been covering and reorganization into a tighter and more contemporary program can also be part of the answer in meeting new needs and stepping up the intellectual rigor of advanced study. In chemistry, for example, what has long been considered the basic work in the major can now be completed by spring term of junior year, according to Prof. James F. Hornig, and the time saved can be devoted to student research and working with faculty members or graduate students on special projects. This contraction was accomplished mainly by dropping analytical courses and counting on superior students to acquire analytical knowledge and concepts in a few intensive sessions and in their individual research.

The independent research alluded to is now part of the senior-year work of just about every major. This is accomplished in advanced seminars in the humanities and social sciences and in special laboratory projects in the sciences. In all cases the individual investigation vestigationinvolves working closely with a faculty member on some specially selected topic or project, with a paper or thesis usually growing out of this work. The honors major offered by every department to high-ranking students puts even heavier emphasis on individual research under an adviser.

In addition to the straight departmental majors, which may take a regular or honors form, there is wide opportunity for the so-called modified major, consisting of ten courses or more instead of the usual eight. For example, seven philosophy courses can be tied to three religion courses for a modified philosophy major, or six economics courses can be grouped with four related courses in mathematics and the social sciences for a modified economics major. This kind of major is especially prevalent in the social sciences where studies are increasingly problem-oriented.

Somewhat more specialized than the modified major, interdisciplinary majors such as Public Administration and International Relations also exist in the Dartmouth curriculum. A special major in Mathematics and Social Science is offered to honors students to give them background for graduate work in certain areas of the social sciences in which mathematics is employed - in economics, psychology or sociology, for instance.

The central and significant thing emerging from this outline of change at the upperclass level is that the flexibility and independence once available only in graduate study are now characteristic of undergraduate work as well, though not to the same degree, of course. What with the new distribution allowance and the great variety in major programs, the serious student - and especially the one wanting to do advanced work on his own - today has the chance at Dartmouth to put together an educational program that is virtually tailor-made to his individual needs and interests. And it can be carried out with whatever intellectual vigor he is capable of mustering.

The Effect of Graduate Programs

This report on postwar educational change at Dartmouth is concerned only with the undergraduate program, but mention must be made of the enlargement of graduate studies at the College because they are having their influence on what is developing at the undergraduate level. Dartmouth at present offers the Master's degree in biological sciences, chemistry, geology, mathematics, and physics, plus the degrees at the associated schools. The Ph.D. degree was revived in 1962 and can now be earned in five fields: mathematics, physics, molecular biology, engineering at the Thayer School, and physiology- pharmacology at the Medical School. Proposals for other doctoral programs, some outside the sciences, are being prepared by a few departments. When the College decided to respond to the growing demand for men trained at the doctoral level, it made clear that it was doing so selectively in areas appropriate to Dartmouth and that it intended to have this graduatelevel work carried out within the framework of the College's primary liberal arts purpose and in ways that would strengthen the undergraduate program.

To illustrate the vital effect a graduate program can have on a department's undergraduate strength, two points can be drawn from Dartmouth's highly respected Mathematics Department. The brightest math students with advanced standing are able as undergraduates to take the courses given for graduate students, and this is happening in every graduate math course, according to Prof. John G. Kemeny. A second strengthening factor is represented by the case of Prof. Ernst Snapper, a distinguished mathematician who came to Dartmouth in 1963 to teach graduate courses and work with Ph.D. candidates. Professor Snapper by his own choice is in charge of the undergraduate honors sequence, Math 7-8, and is teaching one section in addition to his two graduate courses and work with the Ph.D. group. In both courses and teaching the College's undergraduate math program is thus extended and given exceptional quality.

In physics also the brightest students are permitted to take graduate courses, and in laboratory projects they work side by side with graduate students. As in math, this amounts to doing graduate work in senior year.

The College's decision to expand graduate education was made for the additional important reason that it would help in recruiting and holding a first-rate faculty of university caliber. This new breed of faculty (to use a phrase in high favor in educational discourse about students and professors) has had its own special influence on Dartmouth's changing program of undergraduate education. The modern professor, more oriented to his discipline than to general education, prevails at Dartmouth as elsewhere. Trained in graduate school through the doctoral level and in many cases the post-doctoral level, he brings to his teaching very definite ideas of what constitutes academic competence. He has thus been responsible for tougher, more sophisticated standards throughout the undergraduate program, and happily this dovetails with the quality of the new breed of students.

The present-day faculty also favors a more professionalized approach to what is studied and a greater variety of course offerings. And from the character of the faculty have come not only changes in the curriculum but also the growing prevalence of seminars, tutorials, and independent work under faculty guidance.

The teacher at Dartmouth today gives a great deal of himself to his students, and there are no signs that this is done with the reluctance that has produced rebellion on other campuses. Students who take "the business of learning" seriously have more generally open to them than in the past the opportunity for a close academic relationship with members of the faculty, from instructor through full professor.

Much of the research that faculty members are carrying on is made possible by outside grants. Although small by the standards of the big universities, sponsored research at Dartmouth in 1964-65 amounted to nearly $4 million. Most of this was for projects at the faculty level or in graduate programs, and federal funds cannot be said to be having any significant effect on the undergraduate educational program at Dartmouth, except for the indirect effect that comes through the faculty. In the sciences particularly, however, students doing advanced work have some chance to be research assistants, and from the government-financed National Science Foundation more than twenty students this year received grants in the Undergraduate Research Participation Program. Eight of these grants are for students in chemistry, seven in physics, four in biology, and four in psychology.

Financial support from foundations has had far more effect on the undergraduate program than has the postwar phenomenon of federal financing. These grants have encouraged innovation and financed pilot programs that Dartmouth could not have undertaken on its own. Gifts from corporations, a development of growing value, have also been made for specific educational purposes. Foundation support that has been a stimulus to change includes grants from the Sloan Foundation for mathematics and engineering sciences; the Ford Foundation for the Comparative Studies Center; the Rockefeller Foundation for the arts; the Carnegie Corporation for Great Issues, mathematics, and English; the Gilman Foundation dationfor the biological sciences; and the Filene Foundation for the College's human relations studies.

Anything But Unconcerned

How much interest do the students themselves have in the educational program and how much voice do they have in it? They are not all paragons of scholastic endeavor, but their concern with curricular matters has never been more substantial and serious, and through the Academic Committee of the Undergraduate Council they are not bashful about making their ideas known.

The students would like actual membership on the faculty's Committee on Educational Policy, but since they would be greatly outnumbered, says Prof. Louis Morton of the History Department, current CEP chairman, such membership would be mostly a gesture and not any improvement over the liaison already maintained between the CEP and UGC committees. By arrangement rangementthe CEP and UGC agendas coincide each year. CEP, having shaken up the first two years of study, is now giving its attention to Great Issues and the grading system, two matters with which UGC has also been wrestling this year. Our undergraduate editor in this month's Chair discusses the seniors' rebellion against Great Issues in its present form. The grading system (A through E) is also under attack, on the grounds that it is tougher than at comparable colleges, is too inexact, and works a hardship on Dartmouth men in their applications to graduate school.

And so we come full circle to one of the pressures mentioned at the outset of this article. Much of significance in the educational program has not been touched upon, but enough has been cited to suggest the mainstream of change: a more mature and varied and flexible education within the historic liberal arts framework of competence and conscience. This is Dartmouth's response to new students, new faculty, and a new society that guarantees more change to come.

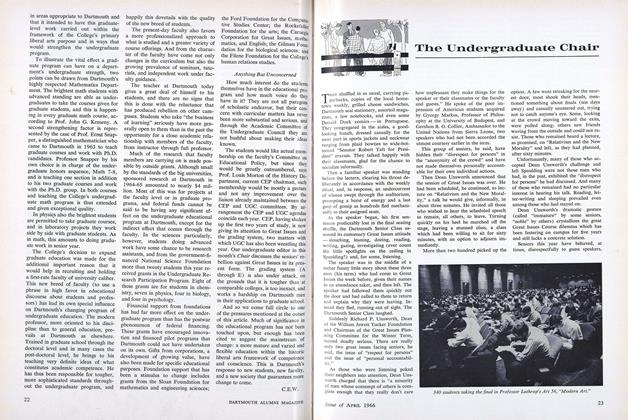

The seminar is increasingly the way in which Dartmouth classes are conducted.

John F. Reinisch '66, a biology majorfrom Holyoke, Mass., working with Prof.Thomas B. Roos on hormones, representstoday's very capable student researcher.

Frank Mwine '67 (left) from Uganda andNaison Mawande '65 from Southern Rhodesia are from lands that now figure inthe global orientation of the curriculum.

The computer is a modern educationaltool and most Dartmouth students todaygraduate knowing the basics of programming a problem by teletype.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTo Keep Pace with America

April 1966 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's "New" Curriculum

April 1966 By JOHN HURD '21, PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH EMERITUS -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

April 1966 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, JOHN S. MAYER -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

April 1966 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

April 1966 By ERNIE ROBERTS

C.E.W.

Features

-

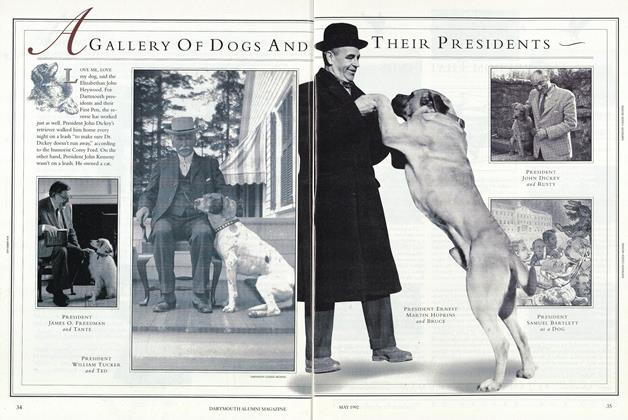

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Gallery Of Dogs And Their Presidents

MAY 1992 -

FEATURES

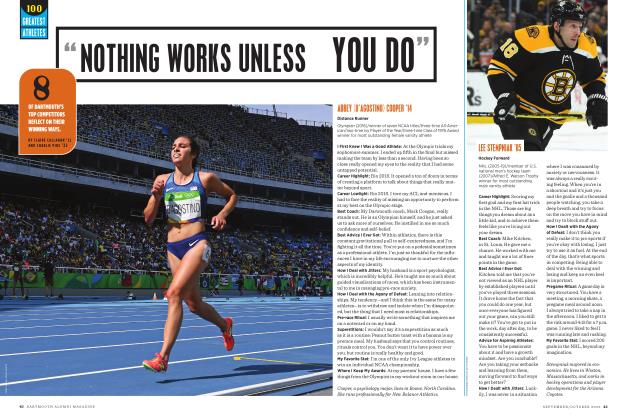

FEATURES“Nothing Works Unless You Do”

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 By CLAIRE CALLAHAN '22 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Nov/Dec 2003 By DAVID DEAL, DAVID DEAL -

Feature

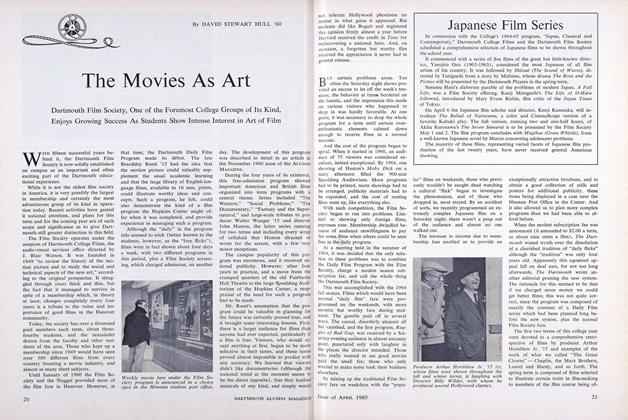

FeatureThe Movies As Art

APRIL 1965 By DAVID STEWART HULL '60 -

Feature

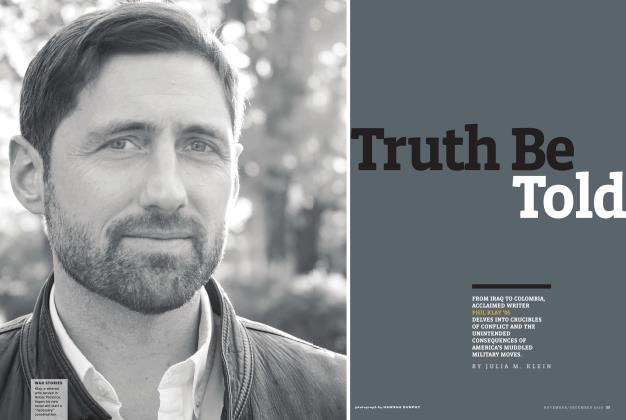

FeatureTruth Be Told

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Feature

FeatureWhat Price Glory?

OCTOBER • 1987 By Ted Leland