A HISTORY OF THE JEWS IN BABYLONIA, VOL. II, THE EARLY SASANIAN PERIOD.

MAY 1967 ROBIN SCROGGSBy Professor JacobNeusner (Religion). Leiden, Holland: E. J.Brill, 1966. xxii plus 341 pp.

The seizure of Babylonia by the Persians from the Parthians began a new and at first troubled chapter in the history of Babylonian Jewry. In Volume I of this series (for a review, cf. DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE, March 1966), Neusner traced the history of the relatively harmonious relationship between Parthians and Jews, which lasted until the downfall of the Parthian empire in 226 c.e. Ardashir, the new Persian ruler, presented a threat to Babylonian Judaism by his aggressive and evangelical attempts to unify his empire both politically and religiously. Under the guidance of the energetic Rav and Samuel, however, the Jewish community outlasted Ardashir and under Shapur (241-273), son and successor to Ardashir, better relations with the government were achieved, and thus more political and religious freedom for the Jewish people.

Such is the historical framework for Volume II of the author's projected five-volume study. To fill out this framework, however, is no easy task, for the sources lie scattered haphazardly within the immense rabbinic corpus, and the brilliance of Neusner's achievement is his success in collecting, organizing, and assessing the relevant data. Furthermore, since the rabbis were not primarily interested in recording historical information, the historian who wishes to reconstruct events is compelled to exacting examination of every logion on the one hand, and to bold conjecture on the other. Neusner is afraid of neither task; he convincingly argues difficult cases and convincingly builds his structure. It is to his credit, however, that he does not try to overstate the case where evidence fails or is too ambiguous.

The wealth of the material involved is too great to permit discussion here. It is not too simplistic, however, to suggest that this history is in essence that of the two great rabbis, Rav, an immigrant from Palestine, and Samuel, a Babylonian-born Jew. As judges they made decisive legal decisions respecting aspects of Jewish life. As politicians they, especially Samuel, worked to reconcile the zealous Zoroastrian Persians to the Jewish community. As theologians they made important contributions to Jewish thought through their creation of liturgical prayers. As biblical exegetes they expanded the knowledge and interpretation of Scripture.

Neusner, however, is no idealist, and perhaps the most interesting sections of his book show beautifully that the rabbi was no ivory-towered saint, nor the people inclined in great awe to follow his dictates. The rabbinic leader was not simply an expounder of Jewish law and theology; he was also "a wonder-working sage, master of ancient wisdom both of Israel and of Babylonia, and privy to the occult." In fact, the author claims that in most respects the rabbi and the Zoroastrian magi were functionally identical. Furthermore the people, like people everywhere, did not always know or care what their religious leaders ordained. On matters necessitating legal papers, such as marriages, the rabbis could enforce their will, while on matters concerning such central religious observances as the Sabbath, the people were desirous of obtaining their leaders' advice. Yet when the rabbis had no legal control, they could only exhort, and Neusner argues that the urgent exhortations sometimes imply that many if not most Jews did on occasion ignore the rabbinic dictate.

What thus emerges is no anemic portrait of an idealized time, but a canvas on which is displayed the complex ambiguities of human existence. For this the author is to be congratulated.

Associate Professor of Religion

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureScotching the Myth About Alumni Sons

May 1967 By RAYMOND SOBEL, M.D. -

Feature

FeatureThe Humanistic Pursuit of Values

May 1967 By ROBIN J. SCROGGS -

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Experimental College

May 1967 By ROBERT B. REICH '68 -

Feature

FeatureRefugees' Friend

May 1967 -

Feature

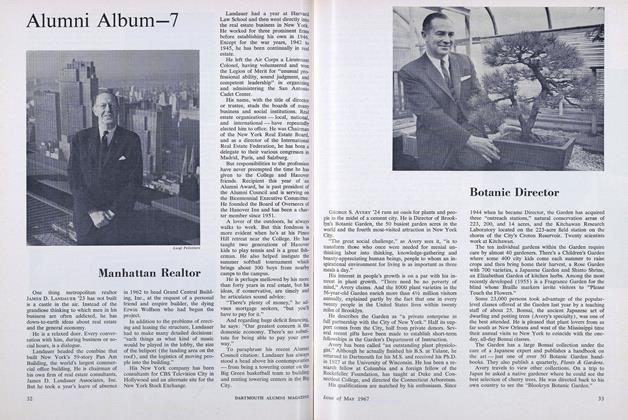

FeatureManhattan Realtor

May 1967 -

Feature

FeatureBotanic Director

May 1967

ROBIN SCROGGS

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

April 1917 -

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

Books

BooksProfessor Gordon Ferrie Hull Jr. '37

February 1946 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

JANUARY 1967 -

Books

BooksTHE BEGINNINGS OF TO-MORROW

May 1933 By Erville B. Woods -

Books

BooksMASSACHUSETTS PROCEDURAL FORMS, ANNOTATED.

APRIL 1965 By W. LANGDON POWERS '34