by Leonard Levitt'63. New York: Simon & Schuster,Inc., 1967. 223 pp. $4.95.

An African Season is a very good book. It is good because it deals with the personal confrontations Leonard Levitt '63, Peace Corps Volunteer teacher, had with the cultural realities of the secondary school and town in which he taught in Tanzania. The account of these confrontations is direct, human, often moving, and often irresistibly funny.

Levitt knows how to tell his story. His prose is colorful, spontaneous, a kind of stream of consciousness writing. There is a "you are there" quality to his graphic and pungent narrative. National Geographictype stereotypes melt away.

Then it was the cold season. You don't think of Africa as being cold, but here in the Southern Highlands you'd find yourself putting on a sweater as it grew dark and then a coat and on toward ten o'clock a blanket around your feet. It was also the dying season.... There seemed to be a death in every village, mostly old people and babies.

We'd hear the drums every evening now.... I remember the chill they had sent through me, hearing them the first night. Jungle drums in darkest Africa (He discovers) these cannibals, these flesh eaters, were a group of half-dressed natives, half drunk on their pombe (home brew), celebrating an afternoon the way we would take in a ball game or shoot a round of golf.

An African Season illustrates without pleading - or even wanting to - the measure of success a Peace Corps Volunteer can realize in fulfilling the goals set forth in the Peace Corps Act. Levitt would be last to say he was "successful." What comes across in these pages is a person who possesses an uncommon capacity to comprehend, empathize, and involve himself in the Tanzanian world in which he lived. His feelings spill out. We learn of his difficulties in dealing with a strange world made up of different smells, creatures, modes of living and eating. Yet we learn a more important thing which unfolds in his writing, of a universality among men which transcends the endless cultural variety. One becomes convinced the potentialities for such transcultural persons to change the perspectives of both the United States and Tanzania are enormous. Added to this is a picture of a gifted teacher who made a positive contribution to the educational needs of Tanzania.

Returning from a summer trip to South Africa and Rhodesia which Levitt characterizes as the white man's world, he makes this observation,

Then it (the journey) was over and I was heading north, back again to the Africa I had come from ... I am back all right, back in the Africa that I know ... I am heading home to Ndumulu.... You had to keep on doing (keep) on believing. Why? It was for these kids ... these boys who got up at six every morning in the darkness to do their calisthenics, who worked all day, who pleaded for extra assignments - please, sir, can we have more sums? - and then on into the night with their kerosene lamp until three a.m. (Italics added)

The book would have been much better if Levitt had chosen to limit his narrative to the rich experiences of his life as a teacher. The second section dealing with his summer trip to South Africa and Rhodesia suffers from a superficiality endemic to all travel diaries. He rarely establishes relationships during the trip on a par with his deeply involved existence in the school and village of Ndumulu. This is a lesson we learn - important, essential writing springs from essential and profoundly engaged experience. The first half of the book is important writing.

Director of Peace Corps Programs

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

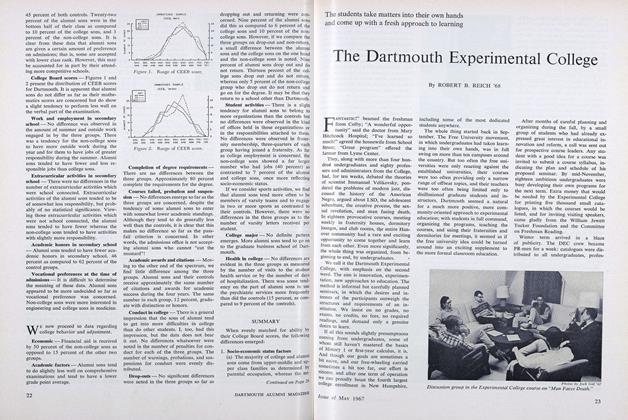

FeatureScotching the Myth About Alumni Sons

May 1967 By RAYMOND SOBEL, M.D. -

Feature

FeatureThe Humanistic Pursuit of Values

May 1967 By ROBIN J. SCROGGS -

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Experimental College

May 1967 By ROBERT B. REICH '68 -

Feature

FeatureRefugees' Friend

May 1967 -

Feature

FeatureManhattan Realtor

May 1967 -

Feature

FeatureBotanic Director

May 1967

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE INTERNATIONAL COURT

October 1932 By D. L. S. -

Books

BooksTHE MANUAL OF CORPORATE GIVING

November 1952 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Books

BooksOUR ARMY TODAY

December 1943 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksKAZANTZAKIS AND THE LINGUISTIC REVOL UTION IN GREEK LITERATURE.

JUNE 1973 By KATHERINE LEVER -

Books

BooksMIGRATION FROM VERMONT (1776- 1860)

October 1937 By Richard F. Upton '35 -

Books

BooksWILLIAM ALLEN WHITES AMERICA

October 1947 By Robert Lincoln O'Brien '91