By Prof. Alvar O. Elbing (Tuck School) andCarol J. Elbing. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967. 256 pp. $8.95 ($3.95 paperbound).

This distinguished book breaks new ground. Far from being another tedious treatise suggesting that businessmen should "be more moral" or "exercise greater social responsibility," it analyzes - and often challenges - the implicit human value assumptions of classical economics. It suggests how these - and other value assumptions about business - distort both the way that society views business as an institution and at the way the businessman interprets his role in society.

The Elbings attack many of the fundamental problems which have plagued discussions of the value issue in business. They point out that this discourse has not been systematic because it has lacked a significant framework which could relate or evaluate the approaches suggested by diverse disciplines like ethics, behavioral science, decision theory, economics, etc. But they do not merely criticize. They propose both a "social framework" to relate the work of various fields and some elements of a methodology to make future studies more systematic and subject to critical evaluation.

The Elbings develop their argument in essentially three stages:

Part I analyzes many of the implicit social value assumptions of classical economics and the implications of these assumptions. This section attacks several basic views: (1) that the economic system is morally good because the market place arbitrates social values, (2) that business is an amoral producer of goods or services and should not be involved in the social area at all, (3) that values are personal issues not associated with economics or the business entity, (4) that such values are irrelevant to discussions of business and economics so long as individual and group action stay within the limits of the law. They effectively set aside the validity of such views.

Part II states the thesis that business is a social system. And its relevance to social values lies in this fact. One cannot choose to accept or deny this reality. It exists. Business organizations affect relationships among the people within them, between the enterprise and other groups in society, and between the entire country and foreign nations. Hence businesses have both an economic and a social output, whether they like it or not. And all decision makers in the organization affect both outputs. Hence, say the Elbings, rational analysis of business institutions and decision making must consider the value component of its being.

Part III sets up minimum specifications for a critical method for studies in the value area. The Elbings insist that a critical method must: (1) start with bonafide questions or hypotheses rather than dogma or assumptions, (2) proceed through an explicit method of argument which disciplines thought from data to conclusions, (3) use rigorously defined words or symbols which provide a clear basis for reproducing the argument and measuring or evaluating conclusions, (4) end in conclusions which are not fixed dogma but are susceptible themselves to inquiry. The "non critical" methods often used in past value studies must be abandoned in favor of more rigorous methodology for analyzing value issues. And they cite some behavioral science contributions in perception, learning theory, and psychology as meeting the requirements of their "critical method" in the values area.

But this is not a book on methodology. Throughout the book - but with special emphasis on the last chapter - the authors express their main concern: that the value rationale underlying classical economic theory is seriously inadequate. They feel that it is essential to look beyond the capacity of a given economic system merely to produce economic outputs or wealth. Any thoughtful analyst should consider the ways that the premises of the economic system play upon the values of the people who operate within it. And, conversely, he should also understand the ways in which the institutions of the system themselves produce changed social values in addition to their economic output.

The Elbings have taken on a formidable task in an unexplored area. They have analyzed their problem with imagination and have presented their arguments lucidly and with force. Although the reviewer would like to have seen more explicit treatment of some current economic analysis approaches which impinge on this area - such as utility theory, multiple-criterion systems analysis, and some aspects of welfare economics - treated in greater detail, the authors have unquestionably opened broad, new horizons for the analysis of a complex issue. Perhaps they have taken a giant step in moving discussions in this important field from the dim realms of unstated or unsupported hypothesis into the amphitheater of critical analysis.

Professor of Business Administration

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

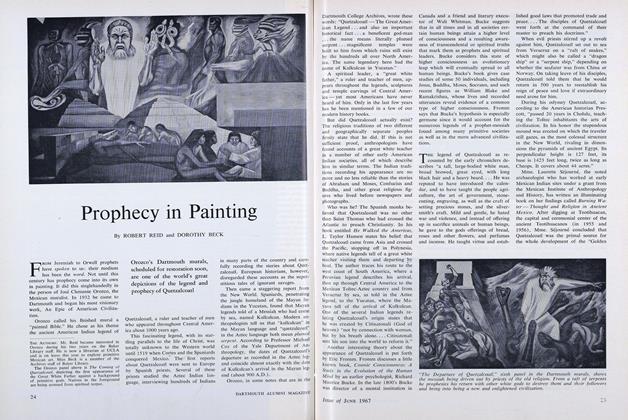

FeatureProphecy in Painting

June 1967 By ROBERT REID and DOROTHY BECK -

Feature

FeatureThe Wallace Affair

June 1967 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1967 -

Feature

FeatureAN ATHLETIC SUMMING UP

June 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

June 1967 By RICHARD G. JAEGER, JAMES W. WOOSTER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1967 By ART HAUPT '67

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

January 1953 -

Books

BooksOUT OF REVOLUTION.

December 1938 By Alexander Meiklejohn. -

Books

BooksTHOUGHTS FROM ADAM SMITH.

JUNE 1963 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksUSING INFORMATION TO MANAGE.

FEBRUARY 1969 By J.M. TURNER. PH.D. THAYER '66 -

Books

BooksWINDOW IN THE SEA.

December 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksDartmouth Authors

MAY 1985 By Mark Woodward '72