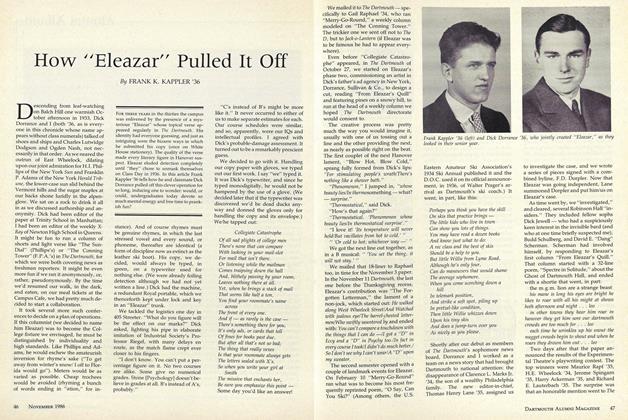

Anyone who publishes a book of photographs is certain to be scolded by readers for omitting the best picture of all - although no two, of course, will agree on what picture that is. Right off the bat, Ralph Steiner is in trouble with this reviewer. One of my favorite Steiner photographs is missing from this collection of his works. That is not surprising, since Steiner has chosen only 101 images from nearly six decades of serious camera work. But it deprives me of a chance to make a point about what sets Steiner off from Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Weston, Paul Strand and some of the other giants of the art whom he hobnobbed with or studied under, and about whom he talks pithily in a highly engaging biographical introduction.

Although he disparages his intellect as of Commencement (a recent perusal of his College record, he says, showed him "exactly in the middle of my class statistically. We were a lot less bright than college students today or marking is now a lot more generous"), Steiner, who moved from New York to Thetford ten years ago, emerges as a philosopher, a sort of East Coast Eric Hoffer, about as simple and homespun as Robert Frost or Steiner's late Vermont neighbor, Allen Foley.

The missing picture is that marvelous proboscis-enhancing wide-angle close-up of Jimmy Durante that ran in the fifth issue of Life (December 21, 1936) and which resulted from Steiner's interest in cloud photography. "At Dartmouth College I met nature photographically in the form of New Hampshire," he says near the beginning of his text. He had taken up photography and fled Ohio to escape the family's Cleveland brewing business. Hanover, the Ledyard Canoe Club and outdoors-loving Professor Leland "Doc" Griggs, whose photography class consisted solely of Steiner, shaped the fugitive into a superior nature photographer. A year after graduation with the Class of 1921, he published a book of his Hanover photographs, which included painting-like soft-focus studies of students dwarfed by campus elms, windows glowing in snowy night, winter-nude saplings leaning over whitened river banks.

After studying with Clarence White ("White hired a design instructor to dose us regularly with design. . . . Only a Prussian photographer might set up his camera, saying: Now I make violence by the use of diagonals"), he got a job as an engraver; met Stieglitz ("Whenever he talked he played Moses bringing the tablets down the mountain"); drifted into commercial photography in New York; and turned from pictorial gauzy images to super-sharp ones ("I could not afford proper lenses and shutters. I bought spectacle lenses of different focal lengths for about a dollar each, and built them into paper tubes ... to cut down light I made tiny holes in black paper as lens diaphragms. Such small openings made everything sharp from near to far"), perforce anticipating by a decade the West Coast "f/64 School" of Weston, Ansel Adams, and Imogen Cunningham. He encountered Paul Strand ("just about the most grimly serious person I'd met in my life ... a walking Sword of Rectitude.... Like Alfred Stieglitz, he had no difficulty in using that awesome word truth") and, stunned by Strand's work, went back to Square One, seeking to elicit texture, "to make wood look like wood and stone look like stone."

How well he succeeded, in this and in seeing the shapes and patterns and contours of trees, grass, and clouds, the artifacts of commerce, inhuman buildings and human faces, can be seen luminously, in the beautifully defined letterpress reproductions of his prints that the Wesleyan University Press has achieved with ultrafine-screen plates on highly calendared paper.

There is no representation here of the other side of Steiner, the motion-picture documentarian. He did, after all, shoot Pare Lorentz's 1936 tlassic of what was not yet called ecology, The Plow That Broke the Plains, and, with Willard Van Dyke, the 1936 landmark film of what was not yet called urbanology, The City, with Lewis Mumford's graphic commentary. He even, "served time" in Hollywood.

Which brings us back to that missing picture. Seeking to get his fill of the sky, the cloud-loving Steiner sent to England in the mid-1930s for the new-fangled 180-degree wide-angle lens called the "fish-eye." He got some skies and landscapes to rival those of Weston, Adams & Co. But I'm not sure that any of those deep-dish seekers of truth would have had the humor to turn the fish-eye lens also on that magnificent piece of American topography, the face of James Francis Durante.

Steiner's shot of the Schnoz for Life.

A POINT OF VIEWBy Ralph Steiner '21Wesleyan, 1978. 144 pp.-$19.95

A long-time editor of Life magazine, FrankKappler now is a senior editor of People.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

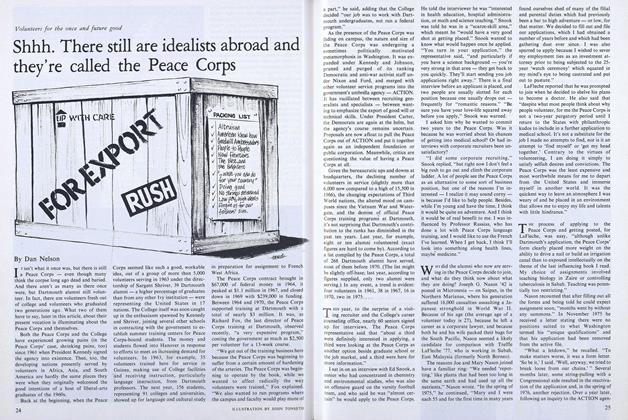

FeatureShhh. There still are idealists abroad and they're called the Peace Corps

June 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

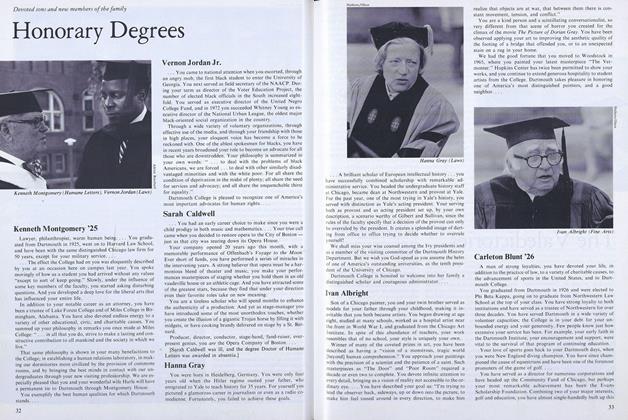

FeatureHonorary Degrees

June 1978 -

Feature

FeatureThe Valedictories

June 1978 -

Feature

FeatureFancies, Toyes and Dreames

June 1978 By Mark Hansen -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

June 1978 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON -

Article

ArticleBad Times to Big Time

June 1978

FRANK K. KAPPLER '36

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Notes

March 1948 -

Books

BooksROWENA: THE SKATING COW

December 1940 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksSCRAMBLED EGGS SUPER.

May 1953 By Maude D. French -

Books

BooksTHE SUPER SUMMER OF JAMIE Mc-BRIDE

APRIL 1971 By ROBERT O. WHITE '54 -

Books

BooksMorning Sunsets

APRIL 1932 By Wallace Rusterholtz -

Books

BooksModern Short Speeches

August 1924 By Wm. E. Utterback