THE COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

'67, CANADIAN MINISTER OF TRADE AND COMMERCE

MARKING as it does the first real turning-point in the life of every graduate, this day is one which will always have reserved to it a special place in your memories. Today you are accorded a rare honor, awarded less for your accomplishments, signal as they have been, than for the promise you have shown of far greater achievements to come. And before you lies the true test of your keeping of that promise, as you apply the lessons of your past to whatever pursuits you choose to follow over the years ahead. We who are privileged to share in this great moment in your lives are all highly honored.

Given such an opportunity, I am bound to seize upon it, recognizing the fundamental similarity between the importance of this day in your development as mature individuals, and this year in the history of the country I am proud to call my own.

Canada is celebrating her Centennial, the hundredth anniversary of her birth as a nation. Beyond the fanfare that trumpets such great events of a people's history, there lies a profound belief that this year does indeed mark a turning-point in the life and development of your neighbor to the north.

Canadians are now, as you are, carefully reading the lessons of their past. Firm resolve, mingled with some apprehension but replete with high hopes and great expectations, colors the vision of our nation's future. And in this year of national stock-taking and renewal, Canadians are keenly aware that we are celebrating less our past accomplishments than the promise and the challenge the future holds for our nation.

We are now two-thirds of the way through the century which a great Canadian Prime Minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, in a burst of pride two generations ago, reserved to Canada. "The Twentieth Century," he said, "shall be the century of Canada, and of Canadian development." Although, today, we are less inclined to be so proprietary about this turbulent era of dramatic, all-embracing change, nevertheless, I believe it fair to say Canadians are more convinced than ever of the capacity of our country to occupy a useful place of its own in the modern community of nations.

Our place, we fully recognize, will not be that of a "super-power." More than any other nation's in the world today, that burden is inescapably yours to bear. As for Canada, a perceptive Canadian ex-diplomat, Mr. John Holmes, has observed: "We must see ourselves in perspective. We are not a failed great power, we are a self-respecting middle power. ... As a middle power, our role is more constructive if it is played not in isolation but in association with many other countries — with friends and allies and fellow members of the world community."

Foremost among such international associations is the United Nations. The aims and objectives of this meeting- place of the world today are unaltered from those set out more than two decades ago; but the emphasis placed on these various objectives and the direction of efforts to accomplish these aims have undergone a profound transformation in the difficult years since the signing of the Charter. It must be remembered that the United Nations is the instrument of its members. Its successes are their successes. And when it does not succeed in fulfilling the high hopes of its architects, the world is the loser and all countries are involved.

Peacekeeping remains the central function of this organization having as its prime undertaking the resolve to "save succeeding generations from the scourge of war." Beset by difficulties over recent years, and by even more dangerous testing of its fiber in recent days, this effort remains the crucial issue on which the United Nations will be judged. Canada remains prepared to play its role in this essential endeavor. Our attitude is to some degree reflected in the words of your late President, John F. Kennedy, in a similar situation five years ago: "The role of mediator is not a happy one, but we are prepared to have everybody mad if it makes some progress."

Increasingly, however, the focus of attention in the United Nations has been compelled to shift from cold war confrontations between the super-powers and the hotter conflicts between smaller which have nothing to gain from wars, to the plight of those less developed nations of the world whose starvation and poverty can no longer be accepted as ways of life.

Through the Economic and Social Council and a number of Specialized Agencies the United Nations puts four of every five U.N. dollars to work to relieve the sufferings of the Third World, those 77 nations where per capita incomes are less than $250 per annum. To this great work Canada endeavors to contribute her share. Last year we ranked fourth among the contributors to the United Nations Development Program and the International Development Association,' third in contributions to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, and second only to your own nation in contributions to the World Food Program.

The British Commonwealth, too, originally assembled for a different purpose now vitally concerns itself with the problems of the less fortunate partners in that alliance. As the Economist recently noted of the Commonwealth: "The big function that remains is that of providing a bridge, or set of bridges, across the gaping gulf between richer and poorer countries, which so frighteningly tends to be also the gulf between races, between cultures, between former top dogs and underdogs in the colonial system."

The centerpiece of this effort is the Colombo Plan which had its beginnings 17 years ago. Since 1950 this program has seen $BOO million worth of assistance transferred to the Commonwealth nations of South and Southeast Asia.

The problems of the Third World also occupy much of the time and effort of those international trade organizations and negotiations in which both our countries participate. One of the most important aspects to the recently completed Kennedy Round of tariff negotiations in Geneva, within the framework of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, was agreement that the underdeveloped nations of the world would receive, unrequited, the full benefit of the results of these negotiations.

In addition Canada joined with the United States and other nations in a special effort to achieve the elimination of duties applied against those tropical products and industrial materials so important to the export earnings of the less developed countries. A measure of success was achieved in this effort, but much greater progress needs to be made in this direction. Canada and the United States also joined forces in the Kennedy Round to press, successfully, for a world food aid plan designed to channel 500 million bushels of wheat over the next three years to the developing countries that need it but have not the means to pay.

Increased trade is vitally important to the less developed countries in a world environment which over the last decade has seen them lose more, through the adverse movement of the prices they receive for their exports, than they gained in aid from the economically more advanced nations. Through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, through the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, through the United Nations and the U.N. Conference on Trade and Development through all these international agencies Canada is proud to add her voice and her efforts to your constant striving toward an amelioration of the desperate straits faced by two-thirds of the people of the world.

Perhaps more important still for the long run than trade or conventional aid is the international exchange of ideas and of educated men and women between the developed and developing nations. Just twenty years ago there was launched an aid program, the Marshall Plan, eloquently described by Sir Winston Churchill as "the most unsordid act in history." This bold and generous initiative helped the war-ravaged nations of Europe back to their feet.

Today, two decades later, it is perhaps not inappropriate to contemplate a new plan - now directed not east but south and providing not physical but human capital. Europe, in the early postwar era, was described as an under-employment situation in which skilled men and women lacked the physical equipment with which to work. Today, among the less developed nations, a very different situation exists. It is underdevelopment in which the critical lack is the scientific, technical, and managerial skills so vital to the operation of a rapidly evolving economy.

As another Marshall, Alfred Marshall, the economist, has said: "The most valuable of all capital is that invested in human beings."

Our Canadian and American experience bears this out. As John Kenneth Galbraith, the Canadian-born economist who served as your ambassador to India just a few years ago, acutely observed: "A dollar or rupee invested in the intellectual improvement of human beings will regularly bring a greater increase in national income than a dollar or a rupee devoted to railways, dams, machine tools, or other tangible goods."

We have learned this lesson of our development and are now, with you, engaged in sharing our knowledge and our knowledgeable men with the less developed countries.

This is, of course, a field in which the United States is a leader; the work your colleges and universities are doing in helping to develop institutions of learning in underdeveloped countries is worthy of the selfless spirit of the Marshall Plan and in harmony with the true principles of the dissemination of knowledge which knows no geographic bounds. In the 1965-66 academic year, your American universities received more than 80,000 students from abroad - three-quarters of whom were citizens of the so-called Third World. And your colleges and universities themselves sponsored every fourth foreign student, nearly 20,000 in all. Another 10,000 foreign students were sponsored by your private foundations.

In Canada, our program has been much more modest, in keeping with our more limited financial capacity. But we are endeavoring to be as responsive as we can to the educational requirements of underdeveloped countries in the certain knowledge that this provides the best platform from which the peoples of these countries can build toward growth and development. In the last academic year some 3,000 overseas students came to Canada to learn, under Government sponsorship. Nearly half that many teachers, professors, and educationalists went the other way. We are particularly proud that last year four Canadian-built schools in the Little Eight Islands of the Caribbean were opened; an outgrowth of the special affinity between the West Indies and Canada, particularly our Eastern provinces.

The Kennedy Round will help to clear away the barriers faced by developing countries in selling their traditional exports and the goods which they will be producing in the future. But the world needs a total assault on the problems that block the highways to prosperity of the lesser developed countries. Until that is done none of us in responsible positions in the more developed countries can be of easy conscience. To do this, however, all Governments will need the support of an enlightened citizenry fully apprised of the urgency of the situation.

The work is just beginning, but through great international endeavors in the fields of trade and aid and education it is my belief that Canadian-American relations can find their truest and highest expression.

The character of a nation is a reflection of the collective character of its people. The efforts of each one of us are important in determining the measure of success our country achieves in the search for its national goals. In the words of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who set the theme of EXPO 67, our great international exhibition: "To be a man is to feel that the placing of one's own stone contributes to building the edifice of the world."

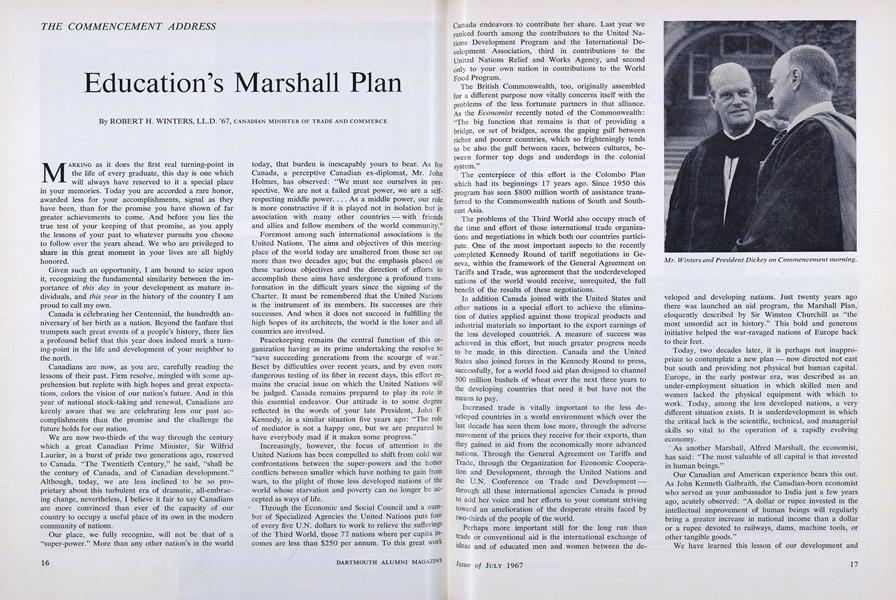

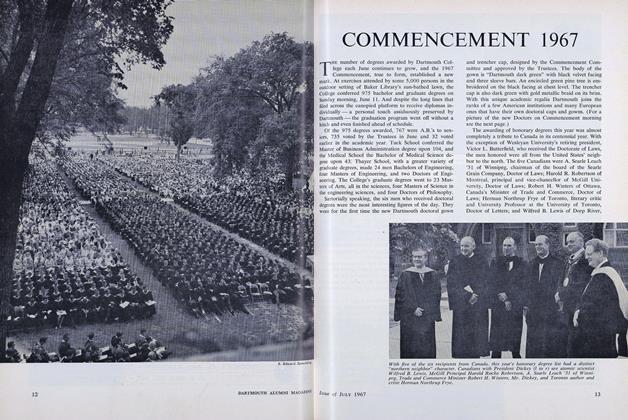

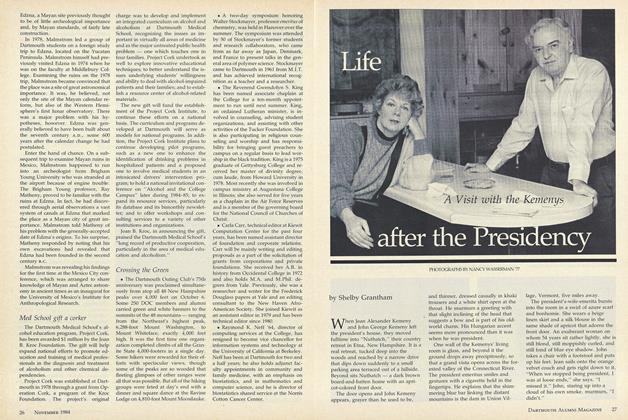

Mr. Winters and President Dickey on Commencement morning.

President Dickey and Dean Seymour leading the academic procession through the split ranks of seniors stretching across thecampus. The white arm bands seen on some seniors were worn as a peace symbol and protest against the war in Vietnam.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Changing and Unchanged

July 1967 By DR. WALTMAN WALTERS '17 -

Feature

FeatureCouncil Honors Four

July 1967 -

Feature

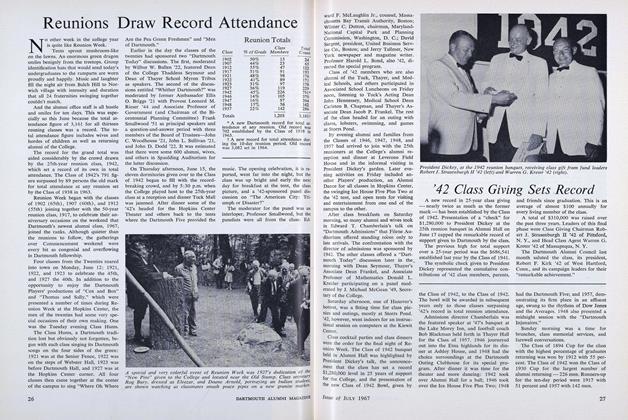

FeatureReunions Draw Record Attendance

July 1967 -

Feature

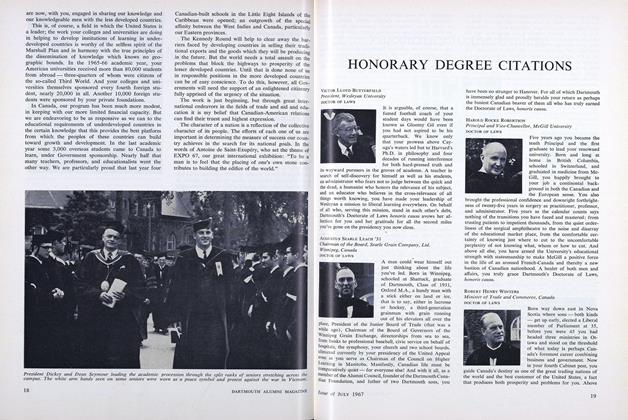

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1967 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1967

July 1967 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to the College

July 1967 By STEVE GUCH JR. '67

Features

-

Cover Story

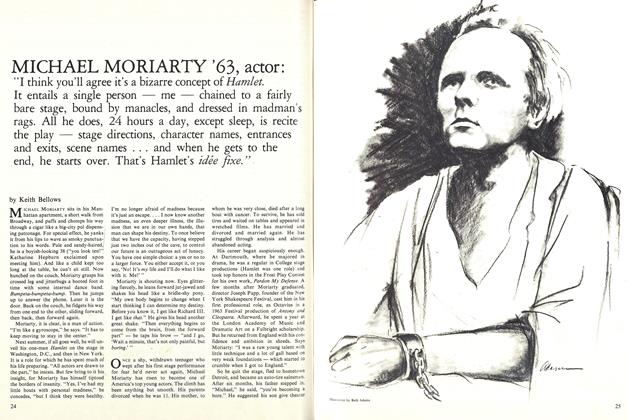

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureSticking to A Phantom like Glue

March 1998 By Park Taylor '50 -

Cover Story

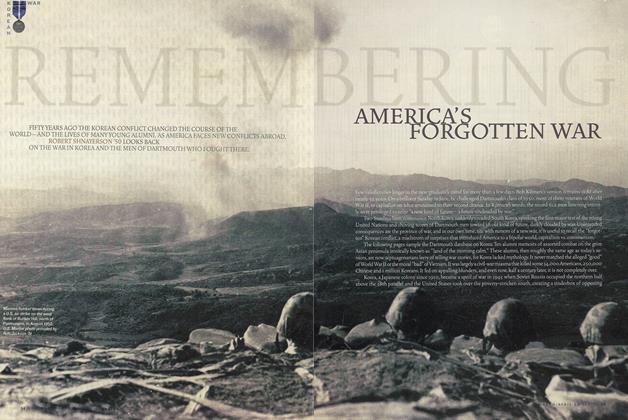

Cover StoryRemembering America’s Forgotten War

Mar/Apr 2003 By ROBERT SHNAYERSON ’50 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GET YOUR CONGRESSMAN'S ATTENTION

Sept/Oct 2001 By RUSSELL D. HEMENWAY '49 -

Feature

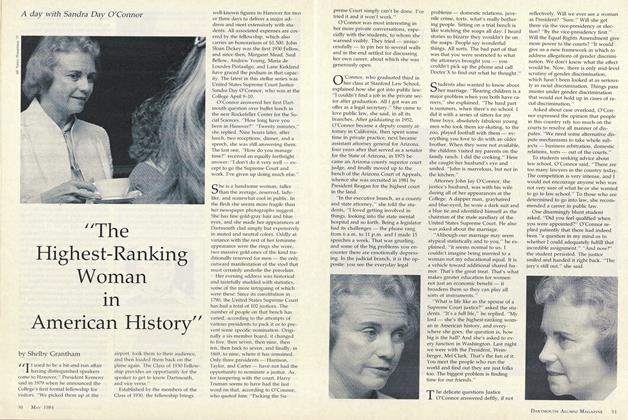

Feature"The Highest-Ranking Woman in American History"

MAY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureLife After the Presidency

NOVEMBER 1984 By Shelby Grantham