The exiled South African poet, who was visiting professor of African and Afro-American Studies at Dartmouth in the spring of '83, remembers Hanover.

It is a sunny, unusually warm late March day in Washington, D.C. Howard University's chapel is filled with the soothing, multi-colored light of the sun shining through stained glass. For Dennis Brutus, the attentive, mostly black, middle-aged audience that also fills the room is less than soothing. This is a tough crowd, Brutus' contemporaries. Well-educated and well-read, many of the people in this audience are writers or poets or teachers or critics. They probably know more about the history of apartheid as well as the American civil rights movement than any other audience he has or ever will address.

He acknowledges the pressure prior to the talk. We have finished the first part of our interview and when walking from the hotel to the chapel he refuses to talk further. I can accompany him but it must be in silence. He must have time to gather his thoughts.

After the speech given informally from notes, and well-received the luncheon, and the questions after-ward, he reluctantly agrees to continue the interview. During the walk from the chapel back to the hotel Brutus refuses to talk again, but this time because of fatigue. He is visibly drained, though when we enter the hotel he offers an oblique compliment. He accuses me of having probed too much during the morning interview. I got him to say more than he intended on the artist and political commitment. "You stole my speech material. You have it there on your tape." (He smiles.)

"What the 300 in the audience missed, 42,000 alumni will get to read."

"Aahhhh. We'll see."

Once in the coffee shop, he sits down heavily and buries his face in his hands for a few minutes before looking up. He orders a Sprite without ice and says firmly, "You have three questions."

About the rules of the interview he is authoritative, firm, and uncompromising. In a poet and activist, these traits are unusual. In a South African they are familiar. The Republic of South Africa is a regimented society, and all of her peoples reflect that to a certain degree. However, to better understand Brutus, it's worth looking at some of the forces that shaped this man.

Fifty-nine years ago, Dennis Brutus was born in what was then Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, but is now Harare, Zimbabwe. His father (Francis Henry) and mother (Margaret) both were school teachers. Brutus grew up in a "coloured" (mixed race) township outside of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, a small city facing the Indian Ocean. The term apartheid would not be adopted officially by the white minority government for another 25 years, but the concept was already a wellestablished part of South African society. His home was a ghetto.

He received a B.A. from Fort Hare University College in 1946 and taught high school English and Afrikaans (Dutch-based language of the white minority) for over a decade. During that time his anti-apartheid activities resulted in government banning orders that prohibited him from teaching, publishing, and appearing in public. This persecution escalated to a fiveyear banning order confining Brutus to his house. In 1963 he defied the ban, was arrested, tried, and sentenced to eighteen months' hard labor.

After being released from prison, he was allowed to emigrate to London, where from 1966 to 1970 he worked as a journalist and teacher. In 1971 he was asked to join the faculty of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

In the past depade, in addition to being a guest lecturer at many American and British universities, he has been an officer or founding member of over twelve organizations devoted to anti-apartheid activities or the promotion of African literature. Brutus is credited with securing the exclusion of South Africa from major international sports competition since 1964.

During his term as visiting professor at Dartmouth, he was encumbered by a protracted and expensive legal battle with the U.S. Immigration Service. However, in September 1983, a federal judge granted him permanent asylum in the United States. The court recognized that his life would be in danger if he were compelled to return to his native Zimbabwe, where he would be within reach of South African agents.

It has been a long journey from a South African slum to political asylum in the United States. Brutus, the prizewinning poet, author of eight books, winner of the Kenneth Kuanda Humanism Award in 1979, makes the most of his now-protected right to speak freely. The slow, methodical way he chooses his words, and a soft, melodic tone of voice hide an angry and still-defiant spirit within. Over the period of nine hours a glimpse of that spirit emerges.

Brutus: "Okay, you better go right ahead, and you had better ask the questions, rather than me asking them. Just one for you, what's your overall impression of South Africa?"

Price: "I'll refer to the comment 'lf you want to write a book about a country, don't stay for more than a week.' "

Brutus: (chuckling) "That's true." Price: "Because the assignment is for the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine"

Brutus: " Wonderful, then you're an ex-Dartmouth. A Dartmouth alum?"

Price: "They were very interested in my tying together our mutual tie to Dartmouth, and some impressions and feelings you had about having been up in Hanover. How did you find the environment for you as a writer?"

Brutus: "Not very productive, but it may not have been the fault of Dartmouth. I was under pressure in terms of the immigration service (U.S.), the deportation order, and worse, the business of raising money to pay the legal fees meant that I had to do an enormous amount of extra speaking, which I would have done anyway, I think, because it related to South Africa, but what it meant was that my writing was minimal. I was in AfroAmerican Studies with some very congenial people there but on the other hand the English department tended to be a little aloof, so that the kind of literary intercourse I normally have I did not have at Dartmouth. Again, it might have been my own fault, I was so busy, but I would not be surprised if I discovered a certain snobbishness in relation to African literature, or Afro-American literature."

Price: "So, to a certain extent while you were there, would you say that you were there under Afro-American Studies, and they had perhaps invited you with more emphasis on your South African tie than on your literary strength as a writer and poet?"

Brutus: "If I were to judge from my interview with Bill Cook, initially, and with President McLaughlin, I would say that that was not the impression I got. They were interested in my teaching African literature certainly, because they felt there was a gap there, but they assumed a certain competence in English literature, which I've demonstrated elsewhere; teaching at Amherst, at Northwestern, at the University of Texas, the University of Denver, and at British universities. When one has lectured at Aberdeen or Birmingham or Cambridge or Oxford, there's a certain competence implied, I think."

Price: "While in Hanover then, did you feel that the Hanover community's interest in South Africa, and/or African literature was sincere, or if it was not, was it perhaps motivated more by ignorance than a lack of sincerity?"

Brutus: "I think they felt a real need, that there was an absence, a gap which could be filled even if only temporarily. In the community as a whole, and I refer to on-campus and off-campus, and indeed the whole Connecticut River valley, I found a very lively interest in South Africa, a willingness to discuss and to raise embarrassing questions. And this may have again worked in two ways for me; for some people it made me a more interesting, more valuable resource, but for others it made me something of an embarrassment. I questioned the morality of Dartmouth's investment in South Africa, I questioned the sincerity of their moral claims."

Price: "In this case, was this the embarrassment of bringing up certain fine, or delicate, points? Was this publicly or privately?"

Brutus: "Oh, very public. We had rallies, demonstrations, protests, speakouts outside the Hopkins Center, outside Parkhurst, oh, we had a great time. We also pulled off a real coup when we arranged for what we called murals without walls. We did an exhibition of paintings, live painters were out on the Green with huge panels depicting the horrors of apartheid. And then these were put on display at [the 1983] Commencement so that all guests assembling were forced to walk by them. And indeed my work there has continued in my absence. The Trustees are still being challenged, and there will, in fact, be events right up to Commencement again this year. [There were. ED.]

"Until such time as Dartmouth discovers its conscience, we will just have to keep going after them. And I hope to be back there. I have, in fact, subsequently spoken at the Rockefeller Center. While I was there I participated in a teach-in with E. P. Thompson, who was there as a distinguished visiting scholar, I think a Montgomery Fellow. I would be glad to give you some of the excellent research done while I was there on Dartmouth's holdings in South Africa and the behavior of those corporations in terms of their socalled adherence to the so-called Sullivan principles. Oh, it was a lively time, and I don't think I'm conceited if I say that I provoked a considerable amount of lively discussion."

Price: "Do you think that the discussion was in general appreciated by the administration and faculty, appreciated as the sort of activity that is absolutely necessary to a place like Dartmouth?"

Brutus: "Unfortunately, no. I think those who it's always split down the middle, or maybe three ways there would be those who welcomed the discussion because it gave expression to their concerns. There were those who remained indifferent, of course, and contrived to be insulated from it. There is always the proapartheid or pro-business, pro-profit element on campus, those who don't care how moral Dartmouth's investments are, or how moral Dartmouth's profits are. I always say that I think they ought to invest in the Mafia, because it would be even more profitable than apartheid. If morality is irrelevant, you might as well be investing in the Mafia. But there were several members of the faculty who were very active with me,, and also very encouraging were the people on the administrative staff, the library, and elsewhere who arranged opportunities for me to speak."

Price: "May I ask who among the faculty was supportive and helpful to you?"

Brutus: "In a sense I would find it invidious to single them out. I think some of them will be glad to express their views, and, more importantly, if you went to The Dartmouth or the material we. put out, you would find the co-signees of letters to President McLaughlin, to the Trustees, and so on, so that it won't be difficult to establish, but I'm not sure I would want to do it."

Price: "In Botswana, July of 1982, I attended a conference called 'Culture and Resistance'" Brutus: "Oh, Johnny might have been there, my son."

Price: "Really? Then you might have heard something about it, but one of the things that stood out in my mind was that it was obviously trying to tie together the needs of the anti-apartheid movement and the artists working in that direction. Both Nadine Gordimer [a white South African novelist] and Richard Rive [a coloured South African writer] said in both of their addresses that no one can impose any restraints on the artist. If there is going to be a political consciousness, it has to come from within himself. An external, almost physical constraint of 'you must be writing about this' absolutely cannot be a part of an artist's activity. Do you agree, disagree? How do you feel about that comment?"

Brutus: "I would like to examine it more carefully, because I think it may be saying two things, and so I would be cautious in my response. I agree entirely that the will to commitment, the will to become an engaged writer, must come from within. There is no way it can be enforced or imposed. Just as the will to be silent, to become irrelevant and peripheral, to lock oneself up in the ivory tower is something that comes from within. It cannot be imposed by a regime that tells you to shut up, and says you can't do this or can't do that. So that the volition of the artist is central but then, to me, the volition of all men and all women is central. Any tampering with the freedom of the individual is offensive to me. So, it would seem as if I am in complete agreement, but in fact I am not.

"The reason is people like Gordimer and to a considerably larger extent, Rive, have used their own abstention from political engagement under the pseudo defense which many writers in the West invoke of this autonomy which implies my right to be indifferent to the sufferings of my fellow man, to shut my eyes to injustice when I see it in my landscape, to blinker myself from that reality. So you can see it can cut both ways. I accept that central autonomy. I don't see it as a way of legitimizing abstention, indifference, quiescence. Now somewhere in between is my own view, which roughly is that the artist, to be true to himself, must always truthfully reflect his landscape, he must confront, and if there is injustice in that landscape, he must confront it, not so much because he is an artist, but because, as a human being, nothing that is human is alien to the human. That is why there must be that confrontation. Okay. Let's leave it at that."

"Was it you asking me about the recent development as they affect Mozambique, and Angola, and South Africa [referring to South Africa's military and economic destabilizing efforts, and pressure on the front-line states not to support the exiled African National Congress]? I don't know if that's one of your questions, if it's not, okay. Go ahead with your questions."

Price: "No. Please go ahead with what you were going to say."

Brutus: "Well, that's one that was asked me last night when I was speaking. One may say many things, of course, but one point seems to me to stand out, and that is the astonishing folly of suggesting that the problems of South Africa arise in the neighboring territories, that they come out of Mozambique or Angola or Lesotho or Botswana or Swaziland or Zimbabwe.

The South Africans who are in the neighboring territories are there because of the conditions inside South Africa. And even if you disposed of all of the South Africans in the front-line states, as long as 80 percent [of South Africa's population] cannot vote, as long as there is racial discrimination and are laws there will always be a South African problem. (Laughs.) You're never going to solve it by attacking Mozambique, etc. You've got to solve the problem in South Africa. I am just amazed at the abysmal short-sightedness of anyone who thinks that the problems of the country can be solved by attacking people in the neighboring countries. Okay, now for your questions."

Price: "Three questions, that's all?"

Brutus: "You had better be economical." (Chuckles.)

Price: "We are two people at the moment with some similar experiences. In this case we both spent a period of time at Dartmouth, with a variety of reactions to that both positive and negative. We also are two people who have spent some time in South Africa. You, a bit distant from it, and me a bit distant from my time at Dartmouth. What about the Dartmouth community living and working there gave you the most despair about the possibility of us having much impact on South Africa?"

Brutus: "That's a difficult one. I don't know of any facet of the community that made me despair, but I know that some disgusted me more than others. And in the long run, I would say that what I found most offensive was the spurious morality, the phoney piousness of people who talked about a leadership role and talked about their high ethical standards. They laid claim to being extremely moral, yet at the same time they knew [of the conditions in R.S.A.] with great clarity because these are well-informed men, mainly men, mark you extremely well-informed. They know about bachelor's quarters in the mines, they know about the homelands, they know about the discarded people, dumped out there in the dumping grounds. And yet they contrive, one, to persuade themselves, and two, to persuade others that they are moral, and that seemed to me the height of hypocrisy. And that more than anything else disgusted me."

Price: "What gave you hope about the community?"

Brutus: "Probably two things, one oncampus and one off-campus. I found many of the students extremely openminded, intelligent, inspired, and willing to hear, willing to listen in spite of an environment that was essentially hostile to honest inquiry. Dartmouth is into fraternities, sports, crewing, football games, track meets, partying, and, of course, getting good grades, which means booking. It is not an environment that encourages honest inquiry; it encourages very interesting and complex speculation. But in terms of honestly saying what are we about, what is this college about, what is this society about, not much of that.

But not withstanding that, I was encouraged by the number of students I met who had open, inquiring, responsive minds. My guess is that there were never more than ten percent of the community, in terms of those I met. And those who resisted information, declined to accept it, refused to expose themselves were as likely to be black as white. The blacks were as anxious to avoid the embarrassment of knowledge as white students, overall. But there was always that ten percent willing to learn.

I found a lot more hope in the community. Men and women, usually middle-aged people working in businesses and stores, and especially people who had gone through the sixties and seventies, who had been involved in Martin Luther King and the freedom rides, riots, and the civil rights struggle, or Vietnam, and the protests against the war, had a residue of moral concern which was backed by an understanding of how this society worked. They knew of the oppressive mechanisms of this country both for repression outside and internally; how one can be very badly bruised in this society if you stick your neck out too far, if you get out of line.

I met a lot of Latinos, Hispanic people who were kind of on the fringes of the community, that couldn't afford to be at Dartmouth, but were around. With them, there was a genuine social concern carried past the point of compassion to the point of action. Out on the sidewalk, outside the bank, they protested loans to South Africa, outside the city council, and on campus. And so by a combination of campus and community I was able to make a considerable impact. I don't think the administration liked it. On the other hand, Dartmouth rather likes the idea of being represented as being willing to have the local radical, the tame Marxist, or whatever it was. (Laughs.) I remember someone introducing himself in the history department and saying 'Oh, by the way, I'm the tame Marxist around here.' And so people know of this kind of tokenism, it's tokenism, of course, of a different kind, but it's almost like the spook that sat by the door. It's a Marxist spook, so .... But of course Dartmouth is quintessentially what American academia is about, and it has this moral schizophrenia, that it postures moral concern but anytime you raise a moral issue, boy, they squash you like a bug. You're squelched; you can't raise it in a faculty meeting, you can't raise it in the senate, and you can't raise it even in a serious academic publication you can't get published. So there is always the fringe stuff, and so one goes with the fringe."

Price: "For my last one"

Brutus: (Laughing.) "This is your last one. Right." Price: "It's more of a personal question

Brutus: "Okay." Price: "I've been home from South Africa for a year, and I guess one of the things I have had to deal with the most has been a great sadness. Now that you've been out of South Africa for upwards to if I'm correct, twenty years?"

Brutus: " 'Sixty-six in two years' time it will be twenty."

Price: "Do you still feel, remember as well, and feel the sadness? Or what is your strongest emotion when you feel most intensely about South Africa?"

Brutus: "I don't know if there is one that stands out. I would have difficulty selecting one. Let me think. The question is usually phrased quite differently, so let me try to answer it the way it's usually phrased. People ask this is a very serious question for exiles people I meet in Cambridge who are from Poland or from Russia, or other parts of the world, they all have the same problem. The problem is how do you sustain the intensity of your feeling, whatever it is, once you've been exiled, once your roots have in a sense been cut off? Many of them cease to write. Someone like Athol Fugard [a white South African playwright] has said that the moment he left South Africa he would never be able to write, therefore he cannot leave South Africa.

I don't have that problem. And maybe that's the best answer. I have found that being in exile for me means very little at one level. That's the level of concern and activity. Because what I confronted in South Africa was Ford and GM and what they stood for, and I have not ceased to confront it. If anything, I confront it now more nearly than I did then. Also, and it seems to me this is the cure for anybody who feels their inspiration drying up, that if you continue to be involved, if you continue to be part of the struggle, then in fact your roots are not severed, that you draw your sustenance and your energy from your involvement in that struggle. And then, that's all."

Kendal Price '7B majored in English at Dartmouth and spent a term abroad in Blois, France. He wrote the first section of an historical novel on black soldiers in World War II as his senior project.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

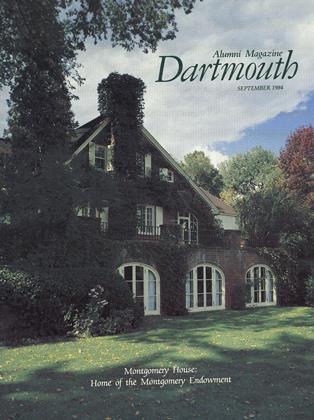

Cover StoryThe Montgomery Endowment Finds a Home

September 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureRichard Eberhart at Eighty: The Long Reach of Talent

September 1984 By Jay Parini -

Feature

Feature"Three ... Forty-two ... Hut"

September 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

Feature"Innocent Ardor and Delight": A Tribute to Richard Eberhart

September 1984 By James Melville Cox -

Article

ArticleRumblings On Fraternity Row

September 1984 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Article

ArticleBob Blackman: Tackling Retirement in Hilton Head

September 1984 By Mary Ross

Features

-

Feature

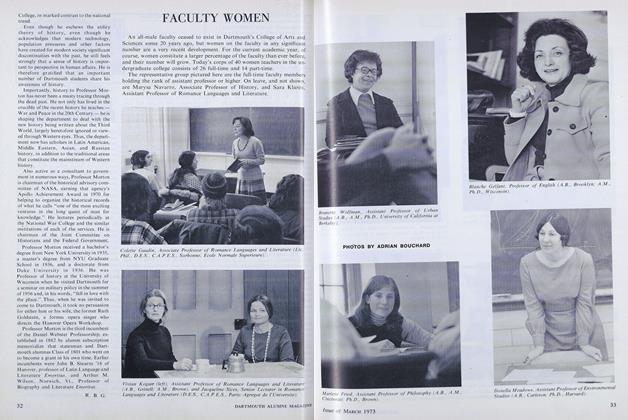

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

MARCH 1973 -

Feature

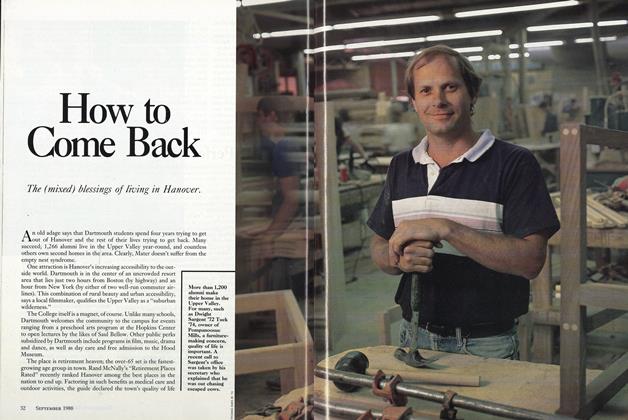

FeatureHow to Come Back

SEPTEMBER 1988 -

Cover Story

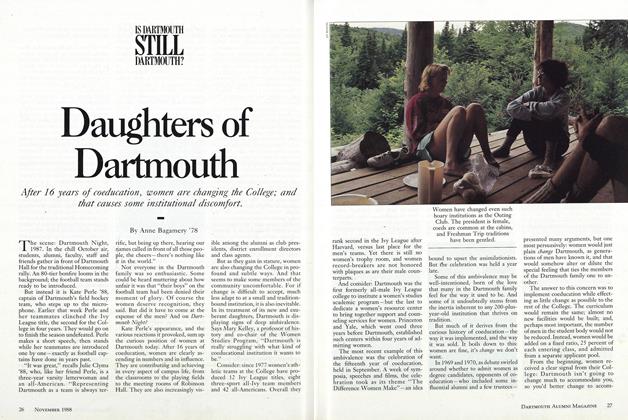

Cover StoryDaughters of Dartmouth

NOVEMBER 1988 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

FEATURES

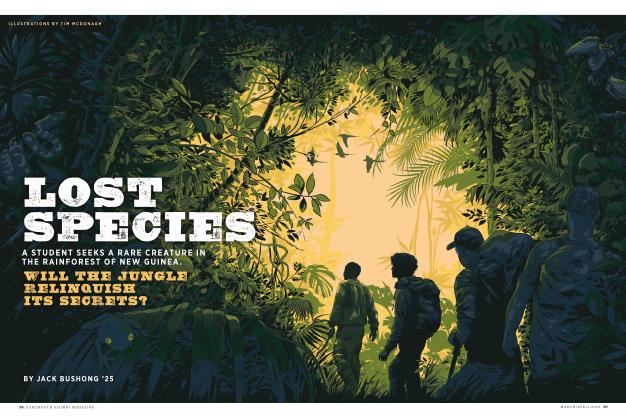

FEATURESLost Species

APRIL 2025 By JACK BUSHONG ’25 -

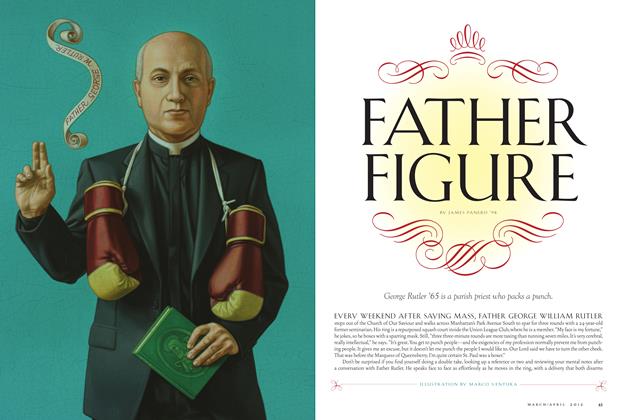

Feature

FeatureFather Figure

Mar/Apr 2012 By JAMES PANERO ’98 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO CHOKE THE LIFE OUT OF AN ATTACKER

Jan/Feb 2009 By VALERIE WORTHINGTON '92