The national debate over college curricula misses the biggest question: what qualifies a person as liberally educated? Opinion by Jay Heinrichs

ALLAN BLOOM'S The Closing of the American Mind did not become a best-seller because the public is concerned about academia's misreading of Nietzsche even though the bulk of Bloom's book is devoted to the subject. Nor did E.D. Hirsch's call for "cultural literacy" draw readers because people want a memorizable list of facts. Americans paid attention to these people, as they did to former Secretary of Education William Bennett, because they themselves are beginning to question the underlying value of higher education. As tuitions continue to float above the consumer price index, people ask whether the liberal arts are worth the expense.

"It will be one of higher education's biggest problems during the nineties," said Dartmouth's associate provost, Bruce Pipes, at a meeting of this magazine's editorial board last fall. "Colleges will be facing the same scrutiny that the medical profession came under during the eighties."

The analogy is apt; medicine has similar problems of expense and access. But academia has a problem that is particularly thorny: a disagreement over what should constitute a liberal education. Call it a purpose gap, a failure to define in layman's terms the intrinsic value of a college degree.

This is nothing new, of course. In the essay that follows, Dartmouth's dean of faculty, Jim Wright, shows that the educational debate has been around for decades. But the unprecedented expense of going to college makes it all the more important to come to a meaningful consensus on the liberal arts. Without it, private decisions over college will necessarily center on economics. How many parents would pay for their child to get a liberal education if they were not fairly assured of a return on the investment in income and social standing? Is there any wonder that careerism thrives on campuses?

Academia, like nature, abhors a vacuum. Rushing in to fill the purpose gap are the prescribers those who would define a limited body of knowlege, mostly from a Western and classical tradition, that all liberalarts students would learn. Pouring in from the other side are the diversifiers people who want curricula to reflect a far broader range of social and cultural realities.

There is a lot to learn under either philosophy. But, on all sides of the debate, precious little is said about what either kind of education does for a person and for society, and what are the questions it seeks to answer. An illustration of the problem can be found in Dylan Thomas's story, "A Child's Christmas in Wales." Among the "useful" presents he received as a boy he lists "books that told me everything about the wasp, except why."

Maybe it is too much to ask for a universal "why" to education in this increasingly diverse world. Still, deciding on a curriculum without defining a purpose for it is putting the cart before the horse. (This is not just a cliche; the term "curriculum" derives from the Latin term for a racing chariot. We'll refrain from any comment about leading student horses to educational water.)

Before we decide what students should learn, we must ask what they should become. What is it that society wants from our graduates today? An awareness of the world outside the campus and beyond America's borders? Adroitness in communicating with others? An ability to recognize or foster change—technological, social, and personal? An understanding of the way the earth was created, and the way it works? Strength of character? Personal happiness? An ability to run a household, sustain a loving relationship, run a business, lead lesser souls? Ernest L. Boyer, president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, puts the aims in the broadest terms: a liberal education, he says, should lead to "a more competent, more concerned, more complete human being." This is a start, though an institution like Dartmouth could come up with a more specific list of what it deems to be its graduates' essential qualities.

The College is, in fact, examining its curricular aims. Led by Dean Wright, the arts and sciences faculty is giving the curriculum its first thorough examination in years. If this effort is like the ones conducted over the past half-century, the changes will be slight. But we trust that the study will be more than the academy's version of the 5,000-mile checkup and that the Dartmouth community will meanwhile avoid the easy prescriptiveness of either great books or the catch-all cry for a poorly defined "diversity." A body of knowledge without a stated meaning can look to the public like academic ballast, material of superficial weight that is easily cast aside later in life. It can appear to be everything about the wasp except why.

Jay Heinrichs is theeditor of this magazine.

"A more competent,more concerned, morecomplete humanbeing" should be theliberal arts' chiefproduct, saysCharles Boyer.

"Before we decide what students should learn, we must ask what they should become."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

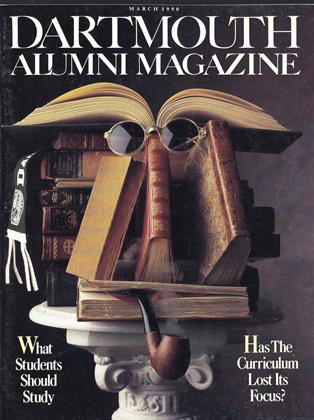

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth's Steady Course

March 1990 By James Wright -

Feature

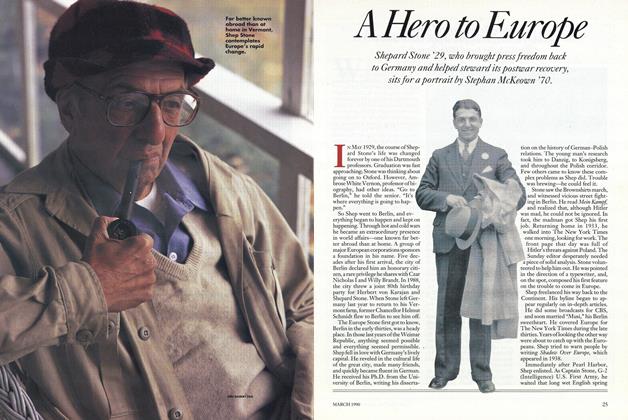

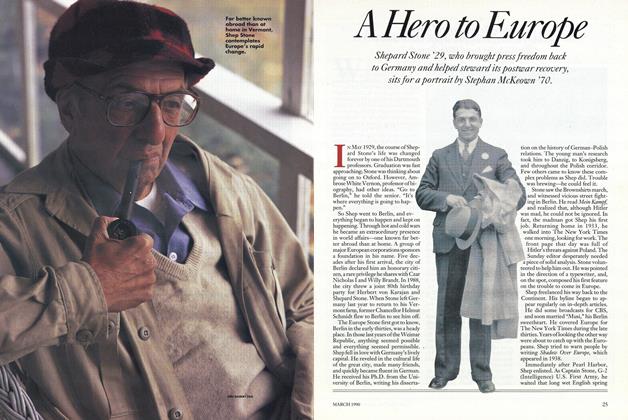

FeatureA Hero to Europe

March 1990 -

Feature

FeatureADDICTED TO CONVERSATION

March 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Feature

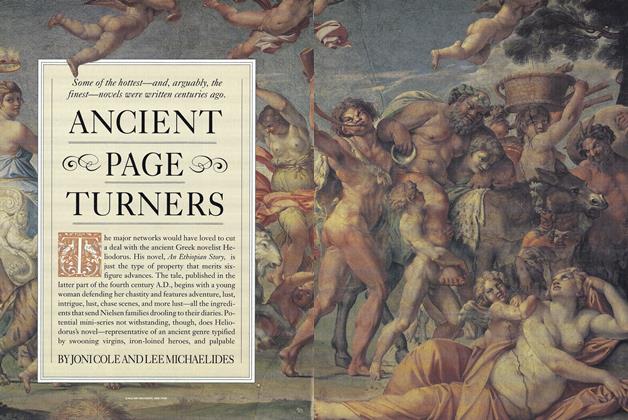

FeatureANCIENT PAGE TURNERS

March 1990 By JONI COLE AND LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

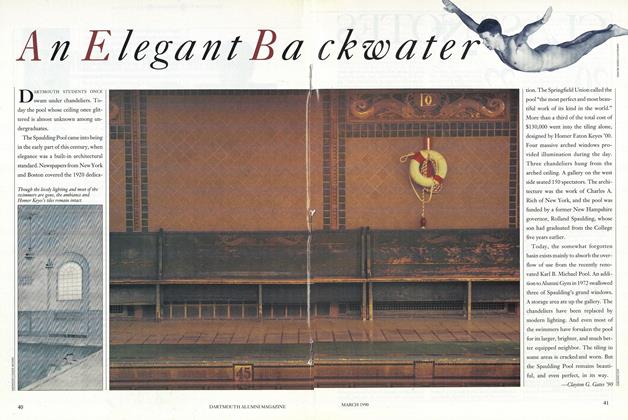

FeatureAn Elegant Backwater

March 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

March 1990

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Hero to Europe

MARCH 1990 -

Feature

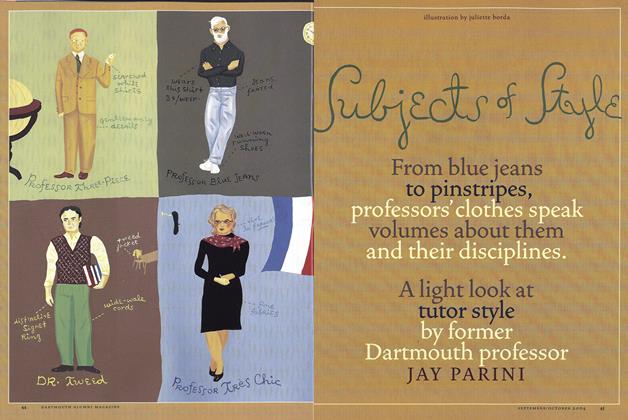

FeatureSubjects of Style

Sept/Oct 2004 By JAY PARINI -

Feature

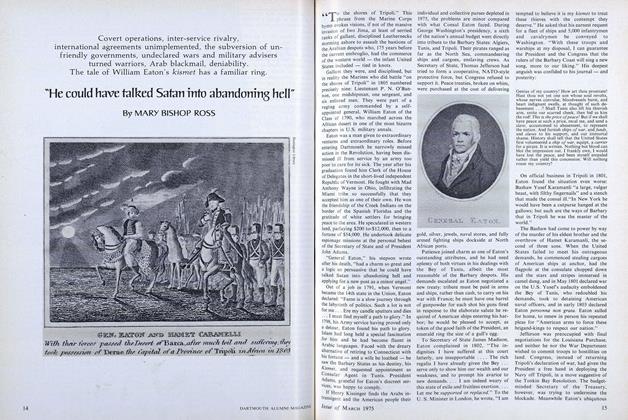

Feature"He could Have talked Satan into abandoning hell"

March 1975 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Dissenting Opinion

Nov/Dec 2010 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

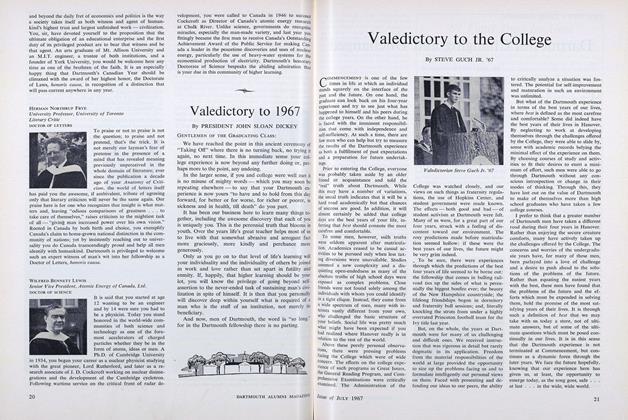

FeatureValedictory to 1967

JULY 1967 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

DECEMBER 1965 By R.B.