By RobertA. Farmer '6O. New York: Arco Publishing Co., Inc., 1967. 131 pp. $4.95.

"One out of every 30-35 children are adopted ... 100,000 children are adopted each year. . . . The number of white children adopted is ten times the number of non- white children." It is with these statistics that How To Adopt a Child begins its explanation of the complex legal and administrative problems surrounding the emotionally charged subject of adoption. This book is part of a "Know Your Law" series "designed to present essential legal information to the lay reader in readable, non-technical language."

Out of the six chapters only two have real substance. The first is a lengthy discussion of the statutory requirements of adoption. Mr. Farmer sets forth, in some detail, the questions of whom may be adopted, who may adopt, who must consent, and, finally, what legal procedures must be followed from petition to final decree. In addition, he has included several charts sketching the basic requirements of the reasons stated. This information will aid the adopting parents in understanding the work of their attorney, but by no means should it be considered a substitute for counsel.

The contribution this "manual" makes to the literature on adoption is in the area of adoption agencies. The author, a lawyer, has treated the agencies with respect, but he is quick to point out that up to now they have not been totally effective in that they have been unduly restrictive and dogmatic. The red-tape often made one wonder if the tail was not wagging the dog. Yet, the best placement is most often done by these rapidly improving agencies because they set up additional standards beyond those created by statute.

Mr. Farmer points out that the agencies have a "threefold" concern:

(1) for the child being adopted,

(2) for the natural parents, and,

(3) for the adopting parents.

To guarantee that the child's welfare is preserved in this spectrum the agencies set up standards in the selection of adopting parents such as race, religion, socio-economics factors, health, age, and intangible factors including emotion, motivation, expectation, and attitude. Procedurally the agency brings the child and the family together for a trial period, and if all goes well it will subsequently insure the legality of the final decree for the protection of all concerned. The author feels that agencies offer the advantages of professional training, disinterested service, preservation of records, confidential relationships, follow-through services and finality.

This book offers good general information on adoption. However, the writing style and sentence structure impede one's enjoyment so severely as to destroy concentration. It brings forth the uncomfortable feeling that the author's purpose was geared to the financial market place, rather than the comfort and benefit of the reader. Out of the 131 pages only 57 are textual, and several of these are almost verbatim reports from several congressional hearings. Although books sometimes do, and should, bring financial reward to their authors, this aspect of them should not be so patently obvious. Despite the fact that the book can be helpful I suggest that one could better spend his time reading elsewhere. Mr. Farmer is a graduate of both Harvard Law and Business Schools. I tend to think that this book is a product of the latter.

Attorney Slive now works inDartmouth's Financial Aid Office

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

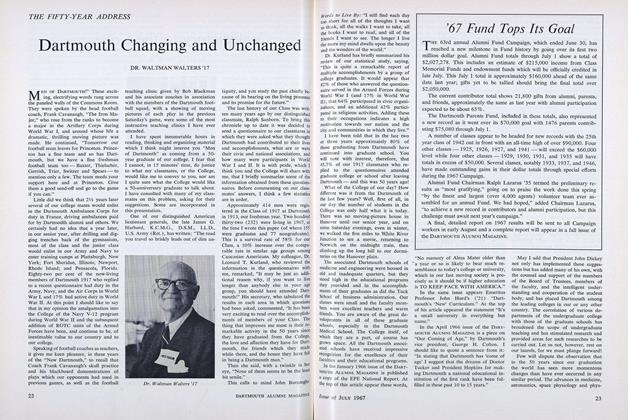

FeatureDartmouth Changing and Unchanged

July 1967 By DR. WALTMAN WALTERS '17 -

Feature

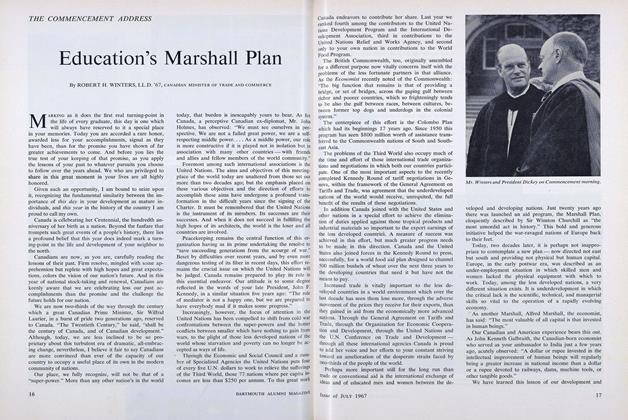

FeatureEducation's Marshall Plan

July 1967 By ROBERT H. WINTERS, LL.D. -

Feature

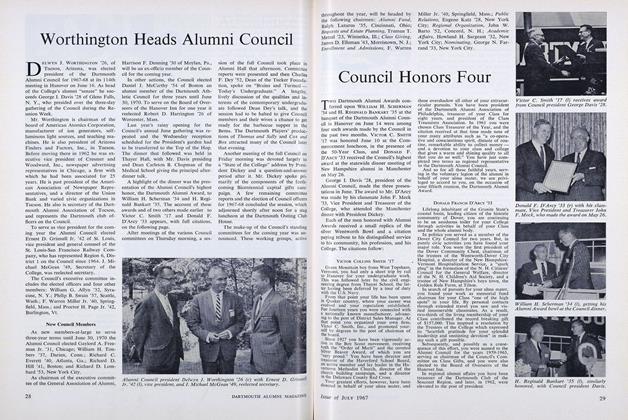

FeatureCouncil Honors Four

July 1967 -

Feature

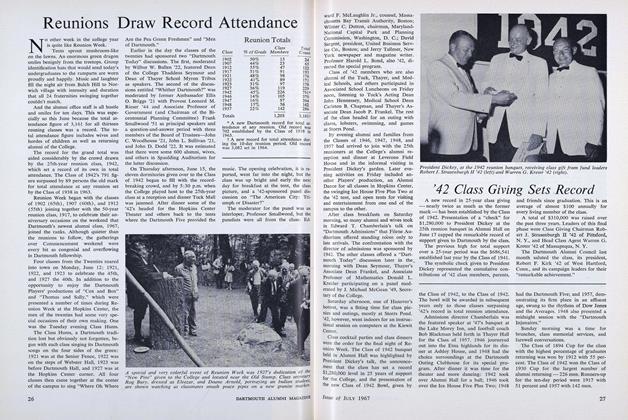

FeatureReunions Draw Record Attendance

July 1967 -

Feature

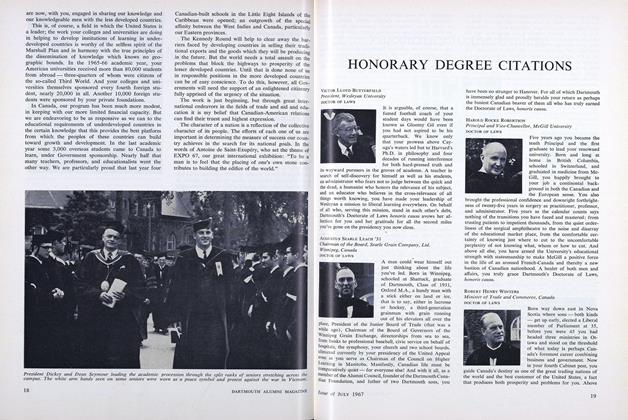

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1967 -

Feature

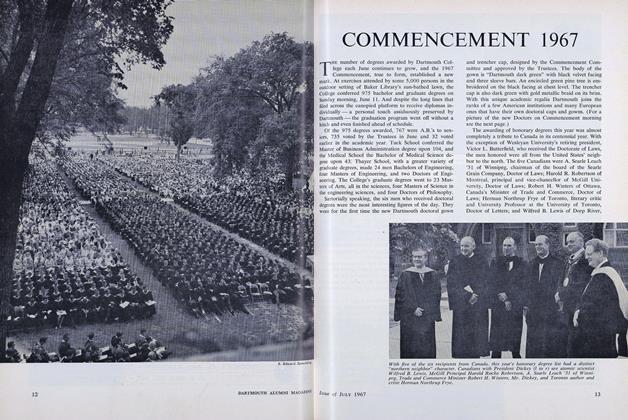

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1967

July 1967

MICHAEL L. SLIVE '62

Books

-

Books

BooksHAWAII WITH SYDNEY A. CLARK,

June 1939 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksAN HERB BASKET,

March 1951 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Books

BooksVERMONT — IN ALL WEATHERS.

November 1973 By PENNINGTON HAILE'24 -

Books

BooksAssessing the Assessors

May 1981 By Richard Winters -

Books

BooksA COMPARATIVE STUDY OF BASQUE AND GREEK VOCABULARIES

OCTOBER 1958 By ROYAL C. NEMIAH -

Books

BooksTHE POLITICS OF DESPAIR.

JANUARY 1959 By WILLIAM G. ANDREWS