By Richmond Latimore '26. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. 157pp. $3.50.

Much, if not most, of the ever-swelling stream of discussion about Greek tragedy assumes that Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides wrote primarily to inculcate ethical, philosophical, or political creeds, to interpret the spirit of their times, or to provide a vehicle for the exhibition of dramatic and histrionic technique. Professor Lattimore admits the partial validity of all these approaches, but his present study is devoted to showing "some of the ways in which poetry as poetry contributes to drama as drama."

To this end the author selects nine tragedies, reviews the setting and action of each, then cites passages from his own translations to show how poetic diction and imagery combine with character portrayal and other elements to create drama. As he says, this is a "difficult and perhaps impossible" undertaking, but this reviewer believes any careful reader must become aware that it actually is the poetry which holds the essential meaning, the music which makes real the action, the unseen and unheard rhythm and rhetoric of the poet's imagination which perform the miracle. The moral is that it is high time to stop reading poetic plays as if they were prose.

Even in the discussion of complex matters, Professor Lattimore's writing is clear, precise, economical. These Hellenic qualities free the author from the bonds of that other kind of criticism which seems to mistake obscurity for subtlety. Surely, as Iphigenia says, "It is right and proper for Greeks to rule barbarians, mother, not for barbarians to rule Greeks. The one is slave, the other free." Surely then it is right and proper, hence Greek, for a critic of Greek thought to be free to discover a fresh emphasis which will help in the understanding of Greek tragedy - and other things.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Examined Life

July 1958 By THE REV. THEODORE M. HESBURGH -

Feature

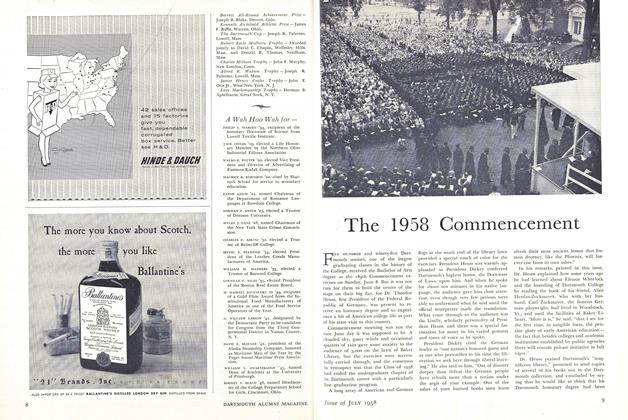

FeatureThe 1958 Commencement

July 1958 By C.E.W. -

Feature

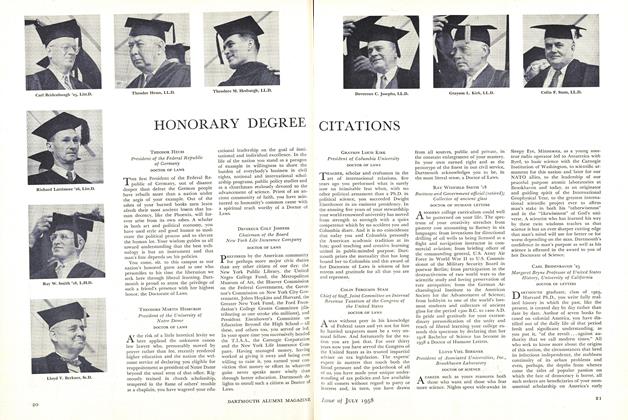

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1958 -

Feature

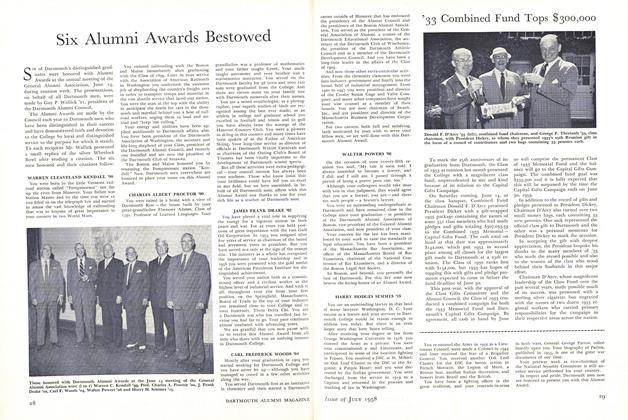

FeatureSix Alumni Awards Bestowed

July 1958 -

Feature

FeatureThe Capital Gifts Campaign To Date

July 1958 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1958 By JAEGWON KIM '58

JOHN B. STEARNS '16

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

DECEMBER 1971 -

Article

ArticleGEORGE DANA LORD

August 1945 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksEURIPIDES II.

July 1956 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksOUR FLIGHT TO ADVENTURE.

January 1957 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Feature

FeatureA Teaching Boon

MAY 1957 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Article

Article"In Classic Dartmouth's College Halls"

DECEMBER 1966 By John B. Stearns '16

Books

-

Books

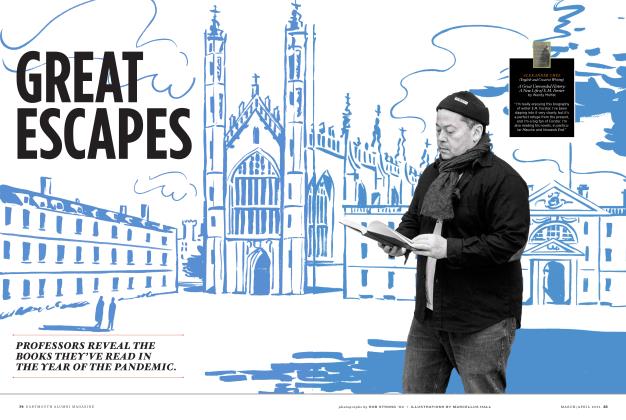

BooksGreat Escapes

MARCH | APRIL 2021 -

Books

BooksTHE CHRISTIAN FUTURE, OR THE MODERN MIND OUTRUN

June 1946 By C. Page Smith '40. -

Books

BooksTHE HOLY SLICE.

February 1974 By H. KARL LUTGE -

Books

BooksYACHTING IN NORTH AMERICA.

March 1949 By Herbert F. West '22. -

Books

BooksNEW ENGLAND SONNETS, ONE HUNDRED SONNETS SELECTED AND REVISED BY THE AUTHOR WITH A FOREWORD BY OGDEN NASH.

APRIL 1967 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksProhibition

FEBRUARY, 1928 By John M. Mecklin