The Wallace Affair (Cont.)

TO THE EDITOR:

While I am just as distressed as various alumni on The Wallace Affair, I can't help but be a little disturbed that our august alumni have not received the current message that 1967 - at least the world of 1967 —is not the same as the world of 1944. 1922, 1930, or even 1963, when Mr. Wallace last appeared on campus.

The forms of protest and the manner in which protest is carried out change. All the alumni have to do is to look around at the headline banners these days to know that within the context of time and the situation, the protests are not the same.

Coming back to Dartmouth, there were no Afro-American societies nor the kinds of involvements of the present. Maybe there were some active protest groups when William Jennings Bryan came to the campus, but the forms of toleration and protests were vastly different.

I guess we talk a great deal about generational differences and also non-communication between generations. The Wallace Affair is a good instance where our alumni of different generations have completely failed to keep up with the current. Far from being simple minded or missing the point, I feel that President Dickey's statement is quite appropriate. He does know the pulse of an undergraduate college. At the same time, Dean Seymour's apology to Mr. Wallace and the latter's response also showed a good deal of awareness of the world of 1967.

I only need to add that your report was masterful.

Tufts University Medical SchoolBoston, Mass.

TO THE EDITOR:

The most disquieting aspect of the whole Wallace episode lay not in the rude and bullying behavior of some angry students, whose enthusiastic excesses must at least be seen in the context of the American tendency to condone student recklessness. It lay, rather, if the article in the Valley News was accurate, in the efforts by faculty members Smith, Radway, Potholm, and Topping (Colby Junior College) to excuse and even to praise this behavior by invoking either irrelevant truisms (for example, that white students should try to understand the depth of Negro resentment) or meaningless imperatives (for example, that a heightened sense of moral outrage justifies an assault upon one of the ground rules of academic discourse).

One principle alone was at stake: the right of a dissenter to express his views. And if anyone has the obligation to uphold the integrity of this principle, it is surely the academic living in a community of scholars. Yet, instead of defenses of the principle, we find recourse to the new elitism of the politically frustrated. For, if the "rush" on the stage meant anything, it meant that the students and faculty involved were so sure that only they had the truth and so sure that everyone else was either too stupid or too naive to perceive this truth that these latter ones had to be saved from the tantalizing falsehoods of the beguiling speaker.

The justifications used by the faculty in defense of the "rush" are startlingly openended. If the moral outrage felt by the rushers was a sufficient sanction for an effort to suppress free expression, then the moral outrage (for that is how they experience it) of the John Birchers sanctions similar activity. And if the students of Dartmouth need protection from the demagoguery of George Wallace, then they also need it against Martin Luther King's recent lapses into the same political art-form.

In short, on matters pertaining to freedom of expression, it is necessary to uphold the objective procedural principle and not to revert to subjective judgment. This does not require a suspension of moral sensibility or a blindness to the obvious truth that various individuals and groups can have legitimate reasons for deploring what speakers say, Nor does it preclude peaceful demonstrations against speakers or their words. But it does mean that the right of expressing dissent is recognized as fundamental; freedom, after all, includes the freedom to be misguided.

Assistant Professor of History, Kenyon CollegeGambier, Ohio

TO THE EDITOR:

For the past week, I have contemplated-writing this letter and have hesitated only because I felt that the College undoubtedly feels regret already at the Wallace visit to Dartmouth. However, I have decided that my remarks need to be said, since they represent the comment of both a Dartmouth graduate and a Southerner.

I teach high school at Chalmette High School, located just south of New Orleans in St. Bernard Parish. Perhaps the name St. Bernard rings a bell in some alumni minds, since St. Bernard High, another school in the Parish, was the site of riots and trouble at the time of integration last fall. I, the parish school system administrators and school board, and the majority of the people of the parish felt deep regret at the incidents which occurred, and felt that our punishment came in the form of national TV coverage which blackened the image and prestige we seek for St. Bernard Parish. Our consolation consisted in our knowledge that those involved were ignorant of what they were doing and unaware of the many forces at work in the country.

I now pose to Dartmouth's administration, alumni, and, most of all, her student body, whether they are ignorant of the forces at work in the South and the nation, from the reactionary standpoint, and conclude with but one statement: if this is the case, and ignorance prevails, students at a respected institution of learning should be willing to hear, judge, and learn what makes a Wallace spring from the South, and from this standpoint, do something to change the situation.

I'm sure many alumni join with me in voicing only criticism for the recent actions on the Dartmouth campus, which, I might add, has only tarnished the respect and prestige formerly accorded our Alma Mater.

With hopes for better from our elite student body,

New Orleans, La.

TO THE EDITOR:

It was with a sense of shock and outrage I read of the treatment of Mr. George Wallace at Hanover. That a guest of the College should be so mistreated by the student body (and outsiders) is incomprehensible. Apparently common courtesy and decency have gone by the board, at least for a portion of the current undergraduates.

Personally, I do not agree with Mr. Wallace's ideas but I'm sure the invitation to speak was extended with full knowledge of what he would probably say. If someone disagreed with him, they were not forced to attend but so attending should at least be reasonably quiet and orderly.

I enclose an editorial clipped from the Daily Progress of Charlottesville, Virginia (home of The University of Virginia) which expresses my sense of outrage more clearly than I am able to do. I never thought I would be ashamed of Dartmouth, but how can anyone rationalize such a happening?

Kansas City, Mo.

TO THE EDITOR:

I have just finished reading the violent outcries of my fellow alumni in the June issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. Perhaps they might temper their reaction after reading the following:

Last summer, my wife and I taught English and drama at a Negro high school in South Carolina. Naturally we were extremely curious about the South and read all the local papers, particularly those from Atlanta, Columbia and Charleston. Ronald Reagan and George Wallace were the two favorite political figures of those papers, both in editorial and reportorial coverage. Wallace was a permanent fixture on the Southern banquet circuit, every weekend seeing him give two or three speeches, sometimes in different states. On several occasions my wife and I were astonished (I tremendously dismayed) to find that Mr- Wallace would refer to Dartmouth when speaking of his popularity in the North and his presidential aspirations. He would tell of how he was applauded "twenty-seven times at Dartmouth College, a landmark of New England intellectual respectability. To the Southerners who heard the demagogue speak, Dartmouth became a Northern hope, a proof that Ivy Leaguers too know that the "Nigras had been gettin' uppity." George Wallace had intended to run in the New Hampshire Presidential Primary. Perhaps he could address the populace from Baker Library steps.

When Wallace came to Dartmouth in 1963 I spent two hours with him as a representative of one of the campus publications. It was an eerie, frightening experience, reminiscent of Penn Warren's All theKing's Men. The Governor, as they called him, was a clever man. He kept us all laughing. We laughed so hard we forgot what he was saying or what we had meant to ask him. (Hitler, said Rommel, was a very charming man.) He offered us good Kentucky bourbon. How could a gentleman or a Dartmouth man refuse?

But I cannot begin to tell you how I felt three years later as I stood before a class of 14-year-old Negro children in Sumter, S.C., and read them a speech by George Wallace using Dartmouth's name. I regretted deep in my soul that I had not spat in that man's face in the spring of 1963. He used us.

My hat is off (my freshman beanie if I haven't lost it) to the students who rocked the governor's husband's car. Sometimes, like the Boston Tea Party and the Warsaw Ghetto, a little violence is necessary.

Los Angeles, Calif.

TO THE EDITOR:

Upon hearing of the Wallace affair, my immediate reaction was one of pride - until the apologies started flying. Not ordinarily a writer of letters expressing my own views, I have been moved to do so by the rash of letters published in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE by Dartmouth men who deplored the whole affair.

That night in Hanover was perhaps the first time in Mr. Wallace's life that he had been on the receiving end of mob violence, but many times he has been on the giving end. Do you remember, this is the man who last year stood idly by while Negro schoolchildren were beaten, their legs broken by ignorant white mobs? This is the man in whose state men are sanctioned by the courts to commit such acts of violence, and are acquitted.

Through all the letters, the same theme runs: "Can we be so impolite as not to listen carefully to the other side?" Such statements imply that logic and reason will prevail over the likes of Mr. Wallace, but from what little I've seen, such a view is naive in the extreme. Did Mr. Wallace come to Hanover for purposes of scholarly debate - or for propaganda purposes? Mr. Roisman '60 says, "But what did the violence and rudeness prove? They proved that George Wallace's view was too sound to be destroyed by reason and logic...." I suppose Hitler's view was similar - hence the war? Reason and logic have very little to do with this case, and I suggest that in place of the word "sound" Mr. Roisman substitute "dogmatic." One plays by the rules of the game, and reason and logic are not the rules of the game Mr. Wallace plays. As Robert Christgau '62 says, "there are times when fire is an effective way to fight fire."

Therefore, I am glad the incident happened, and proud that it happened on the granite of my native state. It told me that Mr. Wallace can get away with demagoguery in the hills of Alabama, but not in the hills of New Hampshire, the seat of our nation's freedom. Perhaps, the next time Mr. Wallace stands by while schoolchildren are being beaten by white toughs, he will harken back to that night in Hanover and, remembering what it was like when the tables were turned, be less hesitant about protecting the citizens of his state.

Too often in the past, emanations from Hanover have been pallid in the extreme, with the academic spirit of the Ivory Tower pervading all. For once, it is good to see a little life from people, be they ever so few, who really care. And to help balance the rich, complacent old grads who will not give this year because of the incident, I have enclosed my own small contribution to the Alumni Fund, reaffirming my faith in the College, and the freedom, I love.

University of GeorgiaAthens, Ga.

A Reply to Prof. Scroggs

Re: Prof. Robin J. Scroggs' article in the May 1967 issue, paralleling today's debate on the war in Vietnam with the Old Testament account of the travail of ancient Israel — after an interesting and valid introduction, the writer makes statements I find unacceptable: "For the first time in our history, as far as I know, our involvement in a war is criticized from all sides. ..."

"As far as I know" is a poor excuse for not having read history. See figures on foreign criticism and home dissent, along with its rejection, during the American Revolution, the Mexican-American War - in fact, all of our various conflicts, except the two World Wars, even the first of which had an appreciable dissent.

The writer says, about the Americans against the Administration's Vietnam policies, "... many ... think we are immorally involved in what was, originally, at least, and perhaps still is, a people's struggle for its own independence." Many more think we are rightly involved in what was and still is a people's struggle for its independence, its battle against being violently forced to become a part of Ho Chi Minh's Communist North Vietnam. But note that serious use of moral standards, i.e. "immorally involved," and then his turnabout in the second-next paragraph, decrying the rejection of criticism and dissent in moral terms. He really can't have it both ways. Then he goes on to make fun of anyone thinking of our Vietnam situation in terms of "the high ethical goals of freedom and democracy" on to the "shining knight" crack. I don't think it's funny. It's the way millions of Americans feel - soldiers and civilians, yes, even government people - not from a religious base, but a political one, because we've found freedom and democracy suit us, and we don't want the quite opposite "dictatorship of the proletariat" forced on us, or, in this case, on some friends who don't want it either.

One of the writer's main points, which, of course, he needs to build up his thesis, is ... this false sense of religious destiny which so deeply and tragically pervades so much of American political culture... " Nonsense! Our government, which was unique and has proved enduring, is the child of eighteenth-century rationalism. As an historian, Elspeth Rostow, says in Rootsof American Tradition, "The rhetoric and commitment built into the Declaration of In. dependence forced on Americans from that day forward a set of moral and philosophic values from which we can never quite escape. In giving us a special history, Providence did not make us special human beings. ... But whether our problem is education or race relations, or a critical decision in foreign policy,... we are haunted —in the best sense —by the truths held self- evident by those shrewd children of the Enlightenment we call the Founding Fathers."

And later on, "I'm glad we had this particular, this curious, historical endowment as we contend with what we cannot escape at home and abroad; because I'm sure that no society which believed in power, in force, and believed that man was basically evil would be able to contend with these problems. If any country can now lead, it is a society hardened and humbled by a need, in the end, to be loyal to the canons of the Enlightenment."

Nor is the President of our country cloaking his problem and his duty or any rejection of criticism in religious terms. Nor are morality and religion necessarily equatable. Actually, most people's - including the present government's - refusal to accept dissenting opinions is based on total disagreement with the dissenters' reading of the "facts" and/or their underplaying of the power drive and worldwide danger of Communist totalitarianism.

The last and principal comparison is in what Dr. Scroggs feels are the great risks the dissenter encountered then and encounters now. (He neglected to mention that Isaiah's advice was so listened to at one point by the Kings of Judah that they gave in and paid the tribute demanded by Assyria. Not that it did them much good in the long run.) As a Time essay on dissent pointed out recently, the continuing, unrepressed chorus makes Senator Fulbright's fears of government repression ridiculous. And Dr. Scroggs'. It was probably just as hard then as now to fight a war you believe you must with your own people snapping at your heels, crying "Surrender!" So they put Jeremiah in the stocks. We don't do that!

San Luis Potosi, Mexico

"No Basis in Fact"

TO THE EDITOR:

The observations attributed to me by Drew Pearson, as reported in the 1921 class notes in the May ALUMNI MAGAZINE, have no basis in fact.

At the six Embassies where I served in the years following the establishment of the Central Intelligence Agency my CIA colleagues were sophisticated, knowledgeable, and cooperative. They contributed substantially to the success of my missions.

Hanover, N.H.

The quoted statement which Mr. Briggs, retired Career Ambassador, objects to says that while he was U.S. Ambassador to Greece "he never knew what Central Intelligence was doing and that the CIA men had more to spend than the American Embassy."

A Double Joy

TO THE EDITOR:

About May 1 the College informed us that our son, Paul, was accepted as a member of the Class of 1971.

Shortly thereafter, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE arrived with its authoritative article indicating there is no correlation regarding fatherson academic attainments.

Truly, my cup runneth over.

Lorraine, Ohio

No Mural Enthusiast

TO THE EDITOR:

I was sorry to read in the June ALUMNI MAGAZINE that the Orozco Murals are to be refurbished, as I never have thought they belonged in Baker.

But the article on them in this issue is a good example of writers being hypnotized by their own rhetoric. And for name-dropping the article wins the Green Derby! The only names missed were John the Baptist and Norman Vincent Peale.

Durham, N.H.

Better Tabulation Proposed

TO THE EDITOR:

I was very much interested in the tabulation of endowments made by the Boston Fund in your May issue. In studying the figures and the names I do not find Columbia University listed and unless I am badly informed Rockefeller Center alone would give it a big start toward $100,000,000.

I believe a more interesting tabulation would be endowment per student where I am sure Dartmouth would outrank many in the top 15 ranked as to total endowment. In such a compilation I believe the names of several smaller institutions would appear.

Denver, Colo.

A Pyrrhic Victory?

TO THE EDITOR:

Will a victory in Vietnam mean our defeat in the world?

With one-fifth the men and one-fifth the firepower, the Viet Cong have stood off the U.S. and A.R.V.N. forces. With each infusion of highly trained men and sophisticated materiel, worldwide belief in the ability of the Americans to quickly dispatch an enemy diminishes. At the other side of the seesaw, Mao Tse Tung's blueprint for home-grown communist revolution wins acclaim as the viable response to American military power.

In Europe NATO is in disarray. According to our own diplomatic officials 80% of popular opinion in Western Europe is against the war. Both here and abroad many informed people feel the United States violates the U.N. charter and her own declaration to abide by the 1954 Geneva Agreements. Many people also feel that U.S. support of six coup d'etat dictatorships in four years, none of which earned much sup. port from their own people, is weird behavior for a democracy. We may well have lost that moral respect without which our leadership becomes powership.

On the battlefield four countries have answered our invitation to send soldiers: Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and the Philippines with a token contingent. Conspicuous in absence and in silence are Japan and India. Absent and silent too are our friends in the Western Hemisphere.

The Communist nations and parties by contrast are vociferous. Lately riven by a resurgence of nationalism, they are nevertheless unanimous in condemning the United States' role in Vietnam. There are even indications that a protracted war might seal some of the fissures which have split the Communist nations and parties in the last decade.

Dare we - shorn of our strongest allies in the free world and confronted solidly by the communist world across the thinning membrane of North Vietnam - escalate further?

And who can tell us what lives, what resources, what bitterness it will cost to quell this 21-year-old revolution? Senator Edward Kennedy reports that South Vietnamese civilian casualty rate is more than 100,000 per year. To what figure will it grow as more men with more devastating weapons stream in?

Next to the maimed and mutilated, the terrorized and the more than a million homeless, the poisoned rice paddies and the burned out villages, the prospects of a government which might dominate or exclude Communists, which might institute land reforms, which might grant dissent a forum is a small and tenuous hope to lay beside this cancerous and repulsive reality. How can we even speak of these refined equities and liberties when man's basic freedoms — to live with his family in his home, to till his field or ply his trade, to die at the hands of nature - are blasted by our tactics of fire, metal, poison, and explosion?

Shoreham, Vt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Changing and Unchanged

July 1967 By DR. WALTMAN WALTERS '17 -

Feature

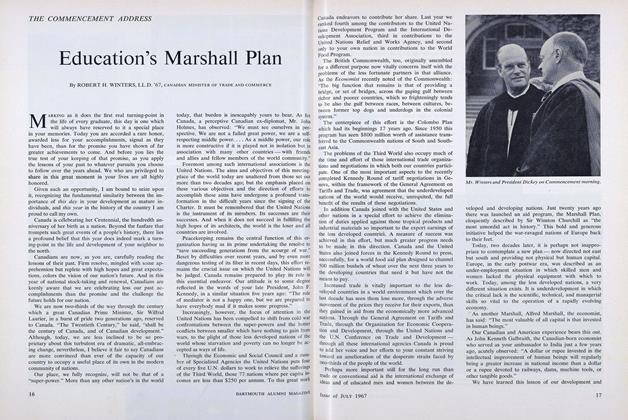

FeatureEducation's Marshall Plan

July 1967 By ROBERT H. WINTERS, LL.D. -

Feature

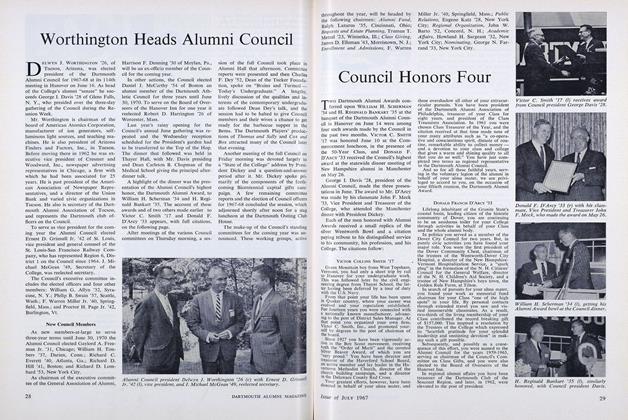

FeatureCouncil Honors Four

July 1967 -

Feature

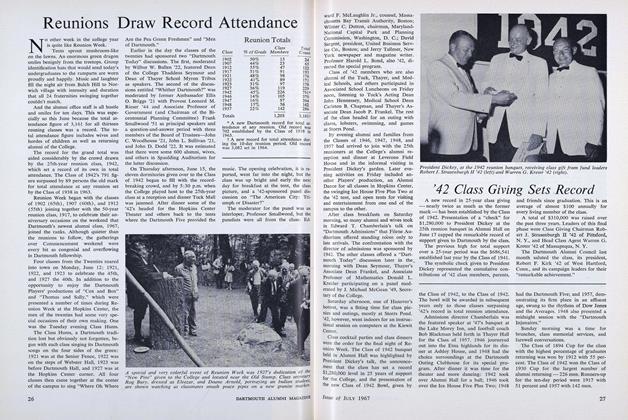

FeatureReunions Draw Record Attendance

July 1967 -

Feature

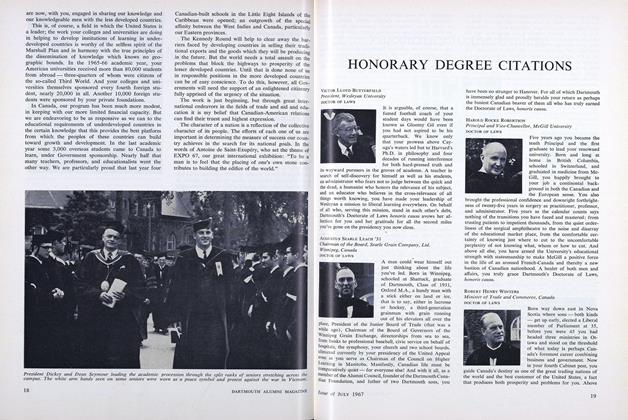

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1967 -

Feature

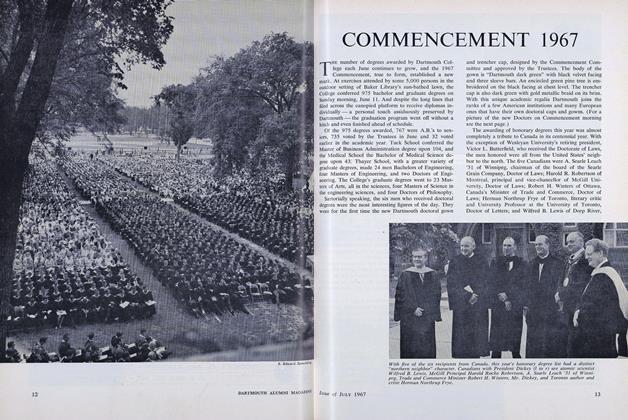

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1967

July 1967