The first in a series of articles about persons and events of interest and importance in the history of the College

Haney Visiting Professor of Economics, 1967-68

THORNTON HALL is familiar to every Dartmouth man, and those who have scanned the plaque at its entrance, or have read a history of the College, know that it was named for John Thornton, Eleazar Wheelock's most generous patron. But many Dartmouth men are not familiar with his business career and widespread philanthropy, are not aware of just what he did to make his name honored in Dartmouth history, and do not know of the distinction of other members of his family.

In the Dartmouth archives are eleven letters from John Thornton to Eleazar Wheelock, drafts of more than 25 letters from Wheelock to Thornton, and a substantial correspondence between Wheelock and the English Trust of which Thornton was treasurer. In more recent years, several publications about his descendants have enriched the story of John Thornton, and told us more about other members of this gifted and public-spirited family: notably the Introduction by F.A. Hayek to the 1939 reprint of the classic economic work, The Paper Credit ofGreat Britain by John's son, Henry; the charming book by E.M. Forster, the English writer and great-great-grandson of John Thornton, Marianne Thornton:A Domestic Biography, about his greataunt, the granddaughter of John Thornton; Standish Meachem's book, HenryThornton of Clapham; and an unsigned article in the March 1966 The ThreeBanks Review on Henry Sykes Thornton, the banker grandson of John Thornton.

John Thornton was born to wealth, and he regarded himself as a steward of that wealth, not only to increase it but also to give away large amounts for worthy purposes. His grandfather, John Thornton, had been a merchant in Hull. Robert Thornton, the father, moved to London, where he was in the Russian trade and was a director of the Bank of England. He is reputed to have left his son John a legacy of £100,000.

John Thornton followed his father in the Russian trade, and prospered. He was an ardent Evangelical - that group in the Church of England who, although not joining the Dissenters, held a more deeply personal religious faith than prevailed in the established Church of the day. To support his beliefs he gave generously: distributed Bibles throughout the world, contributed to missionary activity and to the support of churches in England, and helped many individuals in distress. He functioned as a one-man Ford Foundation, and, according to Henry Venn, the Evangelical preacher, he gave away £150,000 during his lifetime, a sum equivalent in purchasing power to several million dollars today.

Thornton's religious faith was matched by strict standards of personal behavior. He was active in the Russia Company, but refused its chairmanship because that would have required his attendance at dinners where it is customary to have songs and toasts of which he did not approve. According to tradition and Dartmouth song, rum played an important part in the founding of Dartmouth College, but it is unlikely that Eleazar Wheelock stressed the 500 gallons in his appeal to Thornton's benevolence. In a letter to Wheelock on April 26, 1771, shortly before Dartmouth's first commencement, which was enlivened by a barrel of rum donated by Governor Wentworth, Thornton wrote of a man: "I fear he had hard usage and that drove him into the horrid sin of drinking."

John's wife Lucy was a woman of character, sympathetic probably toward what must have seemed to many a prodigal use of private wealth. Her son Henry wrote in his diary: "My mother, whose prejudices as a Dissenter were strong, had prepossessed me on some political subjects. She had taught me to consider the Test Act as a grievance, to suspect no danger in carrying liberty to an extreme and to consider the constitution as intended rather to guard the rights rather than to restrain the liberties of the people."

Strict as were their moral standards, the Thorntons liked the physical comforts of life. Meacham, the biographer of Henry Thornton, says that Gainsborough's portrait of John Thornton "shows him a heavy, foursquare sort of man," and E.M. Forster expresses the same idea in less flattering language: "Slumped and potbellied, John sits." Forster says of Mrs. Thornton's cookbook: "The Thorntons deplored luxury but insisted on having enough to eat. Prayers before plenty. But plenty!" Dartmouth was the beneficiary of John Thornton's concern not only for things of the spirit but also for things of the flesh, for the letters between Wheelock and Thornton in the early, trying years of Dartmouth College indicate that more than once the Thornton purse-strings were loosened by the feeling that the servant of the Lord, on the edge of the wilderness, should be properly housed and fed.

John Thornton's original support of the school that later became Dartmouth College was due in large part to the preaching in England of Samson Occom, the Indian who had been educated by Eleazar Wheelock at his school in Lebanon, Connecticut. Under the sponsorship of the young Earl of Dartmouth, who contributed £50, a Trust of £9494 was established in 1766 for the support of Wheelock's Indian Charity School. The largest contributor was George III who, urged by the Earl of Dartmouth, gave £200. John Thornton, appointed treasurer of the Trust, gave £l00, as did two other London merchants, Samuel Savage and Isaac Hollis, The balance of the Trust came from over 3,000 contributors, including £5 and 5 shillings from Merton College, Oxford, £2 and 2 shillings from the Professor of Musick at Cambridge University, and 10 shillings and 6 pence from the Vice Chancellor of Cambridge University.

AFTER Wheelock's proposal to move Moor's Indian School to New Hampshire, and to found Dartmouth College, the letters to Wheelock from John Thornton and the English Trust repeatedly suggest a fear that missionary funds were being diverted to the more worldly purposes of Dartmouth College. Wheelock on his part more than once reassured his patrons that no funds of the English Trust were being used for Dartmouth. Nevertheless, on November 10, 1773 Wheelock wrote to the Trust suggesting the need for contributions to support the College, "as there is yet no provision made, nor like to be made, that I know of, for the support of the College, or any professor or officers in it, other than that which the independent students made by paying for their education here...." But neither John Thornton nor the Trust showed any inclination to make contributions to Dartmouth College, or to allow any Trust funds to be used for the College. If any of their funds were so used, the operation was well covered up by the accounting legerdermain of Eleazar Wheelock.

On July 22, 1774 Thornton wrote to Wheelock that £460 were still in the Trust,

which you may draw on as the Indian Schools may require it and then I believe we shall on this side of the Water be glad to Testify we fulfilled faithfully what was committed to us and account ourselves discharged from having any direction in future Transactions; truly thankful that through your great watchfulness and Care and unwavering attention to the Schools all has wound up so well. I flatter myself that though as a body we shall be annihilated, as private persons our regard to the Schools will be no way diminished and I hope ever to convince you thereof in my particular.

To make doubly clear that no more funds could be raised in England, Thornton urged Wheelock not to send his son John to "solicit subscriptions." But the letter was friendly, and had the Thornton touch of combining shrewd business judgment with a concern about the state of English morals:

the unhappy differences that subsist betwixt us and America would only expose him to disappointment and contempt and the too general state of dissipation and extravagance that prevails occasions most people to live upon the stretch that really they cannot afford to give, even where they more disposed to be liberal, than I expect they would be ...

A letter of February 1, 1775, signed by the Earl of Dartmouth, John Thornton, and the five other Trustees, reiterated the message that no more help could be expected from England.

With his letter of July 22, 1774, Thornton, as a result of a suggestion from Wheelock, enclosed a message "to the students of Dartmouth College and Moors' School" which Wheelock read to his students. It was mainly a plea for religious faith, but it also had a secular message that many a college president of today, in his gloomier moments, might feel like delivering to his students.

Remember Gentlemen, that you are now in a state of Minority and Discipline: what is expected of you at present is a Cheerful Obedience to all lawful Commands and a strenuous endeavour after improvement in your studies.... I wish, Gentlemen, to recommend another thing to you, which is that you would give attention to the deportment of the outward man striving against every propensity of ferocity of behaviour, or love of rambling about, which is too natural to many at your time of life, and that at proper times, you should enure yourselves to Activity and Dispatch. The Man is often presaged in the boy. If you begin to be active and love Work, it will by Degrees grow familiar, and you will every Day reap the Advantage of it. Whereas an Indolent turn locks up every spring of action and like Drowsiness, in Time will clothe a Man in rags ... I would caution you against Books, Pictures and Conversation, that is any way calculated to inflame the Passions of Lust, which is so deeply rivetted in our fallen Nature that it needs no additional excitement, and will find you work enough to subdue and bring into subjection.

According to Wheelock's reply to Thornton, the letter was received by the students "with universal expressions of Gratitude and Respect."

There is no evidence of a break between John Thornton and Eleazar Wheelock. Apparently Thornton, and probably even more the English Trustees, with the worsening of relations between colonies and mother country felt that people strong enough to rebel against English rule should be able to finance their own schools. There is no record of any reply to the five letters from Wheelock to Thornton from July 30, 1774 to September 12, 1775. These dealt with familiar themes: religious activity at the college, its financial problems, and in a letter (April 29, 1775) just after Lexington and Concord, a political note:

I believe there never was a more dutiful loyal and well affected people to Government, than had ever been in these Colonies till the Stamp Act and the Colonies have ever been propence to peace and reconciliation till these late horrid murders and savage Butchering so inhumanly committed under pretence of reducing rebells to Obedience.

Although formal support from England ended with the exhaustion of the Trust Fund, John Thornton's kindly interest in the schools he had helped to found, and possibly his personal support of Wheelock, continued. Thornton's formal contribution to Wheelock's schools was, so far as the record shows, limited to £100 given to the English Trust. But his personal gifts to Wheelock exceeded this manyfold. In a substantive sense — as distinguished from accounting niceties as to whether his gifts were to carry the Gospel to the Indians, to support Dartmouth College, or to pay the living expenses of Wheelock and his family Thornton was the largest single contributor to Dartmouth in its first five years. It is doubtful whether, without his help, the College could have survived.

In 1768 Thornton gave Wheelock, still living in Connecticut, a "chariot," in which Wheelock's family made the trip to Hanover in 1770. In his will Wheelock provided: "To my successors in the Presidency of this College and School I give and bequeath my chariot, which was given to me by much honored Friend and Patron John Thornton Esq. of London by whose liberality my family has been chiefly supported for a number of years before the present war." The chariot, unfortunately, disappeared some time around the middle of the last century, but no one seems to know exactly when and how.

Letters from Thornton to Wheelock are filled with offers of financial help and WWheelock's letters to Thornton with regret that he has again been forced to avail himself of his patron's generosity. On June 19, 1770, when Wheelock was still in Connecticut, Thornton wrote: "By your letter to Mr. Keen I find you have got about £150 behind hand in your private fortune. I think it is of consequence to clear all when you remove, that I recommend your doing it, and pray let me have the pleasure of clearing you, and draw on me whenever it is most agreeable, that this remain betwixt ourselves."

The following spring Thornton wrote: "I am ready to assist you with £500 out of my private fortune or the double thereof if you judge it needful." How much Wheelock judged it "needful" we do not know, but in October of 1771 he wrote that he hoped that he would not need to draw on Thornton again, and added, "but I see you love to do good."

Wheelock was not going to deny Thornton the opportunity to do good, if that would help to advance the Lord's work. On December 18, 1773,, he wrote that he had drawn bills for £160, "agreeable to that unlimited license, you have so kindly and repeatedly given me." And even in the letter of July 22, 1774, already quoted, in which Thornton made it clear to Wheelock that no more funds were to be expected either from the Trust, or from him, for the support of the schools, he again expressed his desire to contribute what might be necessary for the support of Wheelock and his family. "I was glad to hear you had a comfortable Habitation for your family and, I can only repeat to you that I shall with great cheerfulness assist you with what your occasions may require and, therefore, if you distress yourself unnecessarily on that account I can only wish it had been otherwise."

The "comfortable Habitation" to which Thornton referred was a house on the present site of Reed Hall, moved in 1838 to West Wheelock Street and now the Howe Public Library of Hanover. We know from Wheelock's letter of May 8, 1773 that to help pay for the house "I have therefore drawn a bill on you of this date for £l00 sterling ... and nothing troubles me more at present than a consciousness of unworthiness of your kindness. I trust the Lord will repay you."

Whether Thornton after his letter of July 22, 1774 ever made any personal contributions to Wheelock we do not know. There is no further letter from Thornton to Wheelock in the Dartmouth Archives, but on January 23, 1776 Wheelock received through George Washington's secretary a letter from Thornton which in 1775 had been thrown overboard by a British ship and picked up by an American privateer off Cape Ann. The letter was not preserved and there is no evidence as to its message. Thornton's friendly interest in Dartmouth continued, even after financial assistance had stopped, for he wrote to the Earl of Dartmouth on April 19, 1776: "I hope your Lordship will be so kind as to recomment Dartmouth College to Lord Howe and his Brother that if they will give no first occasion of offence, they may not be wantonly hurt."

In 1783 John Wheelock, then President of the College, made a trip to France, Holland, and England to solicit funds. He was everywhere well received, but had meager financial success. Of his visit to England he wrote: "The day after our arrival we waited on Mr. John Thornton of Clapham as we thought (the Earl of Dartmouth being in the country) our first respect due to an old benefactor. He was civil and kind." But Thornton discouraged Wheelock from trying to raise money in England as "he thought the spirit of the nation would not admit of the measure," and there is no evidence that he personally made any gift to Dartmouth. When John Thornton died in 1790 the Gentleman's Magazine obituary described him as "the greatest merchant in Europe, except Mr. Hope, of Amsterdam," and estimated his fortune at £600,000.

WITH one possible exception, noted later, no other Thornton ever made a contribution to Dartmouth. But John Thornton's descendants played, in varied ways, so distinguished a role in English life that some account of them seems in order to complete the Thornton story. John Thornton's only daughter, Jane, married the Earl of Leven and Melville. His three sons, Samuel, Henry, and Robert, were all members of Parliament, serving a total of 99 years, which may be some sort of a record in Parliamentary history. Samuel, the eldest, continued in his father's business and was financially successful. Becoming a director of the Bank of England at the age of 25, he continued for 56 years—the second longest service of a director in the history of that venerable institution - and was governor of the Bank. Samuel followed his father's interest in good works and religious faith, but never with the philanthropic ardor of his father, or of his younger brother, Henry.

Robert, the second son, also went into his father's business and was active in the East India Company, serving as its chairman in 1813. But he lost heavily in speculation, and after defaulting on his debts fled to the United States in 1814. He died in March 1826, according to his niece, Marianne Thornton, in New York City under an assumed name. Of him, E.M. Forster says: "I sometimes wondered whether he may not have founded a Thornton family in the United States. He sounds capable of it, and his wife had failed to accompany him in exile."

The youngest son, Henry, was the one who most successfully carried on the money-making, religious, and philanthropic traditions of John Thornton, and to these qualities he added an intellectual distinction that his father lacked. After a brief period in his father's business, Henry in 1784 entered a London private bank, in which he became a partner and the guiding figure. His parents were opposed to his going into banking and the grounds of their opposition, as Henry related in his diary, were in the best Thornton spirit: "My father as I suspect chiefly feared that I should be placed under peculiar temptation to keep improper Company by my being a Banker, a point in which he was mistaken. My mother's prejudices led her to think that to cease being a Merchant in order to become a Banker was to descend in life."

Two years earlier, at the age of 22, Henry Thornton had entered Parliament for Hull, and his political position and the profits of his banking firm gave him a foundation from which to promote for over 30 years a campaign of religious activity, popular education, and social and political reform. He had the same urge to do good as did John Thornton, but with a more disciplined approach. His greatgrandson, E.M. Forster, describes him "as a typical Thornton, pious, benevolent, industrious, serious, wealthy, shrewd... What a contrast is the portrait of him, by Hoppner, to his father's portrait! Cold, intellectual, public-spirited, fastidious and full of integrity, Henry stands, and his hand rests upon a parliamentary bill."

Henry says in his diary that his first vote in Parliament was in favor of the treaty of peace with the United States. He was active in Parliament on fiscal and monetary matters, and played important roles as a member of the Parliamentary Committee of 1804 on the exchange rate between Ireland and England, and of the more famous Bullion Committee of 1811. But his influence in Parliament went far beyond finance; he supported Catholic emancipation, parliamentary reform, prison reform, abolition of sinecures, and and abolition of the slave trade. His almost too evident self-righteousness made him a respected, although not a warm and politically appealing figure, but at election time his supporters made political capital out of his unquestioned probity, in doggerel which ran:

Nor place nor pension e'er got he For self or for connection We shall not tax the Treasury, By Thornton's re-election.

This activity as a member of Parliament for good works was matched by private charity that shows Henry Thornton as the true son of his father. He wrote in his diary in 1809 that he had "by the blessings of good Providence, enjoyed a considerable and generally increasing income for the last twenty years. But I have made it my rule not to amass any large fortune."

Henry Thornton's book of 1802, AnEnquiry into the Nature and Effects ofthe Paper Credit of Great Britain, dealing with the problems arising out of England's suspension of specie payments during the Napoleonic wars, is one of the great works of economics. It not only had important contemporary influence, but is recognized by present-day economists as a remarkably penetrating analysis of banking and credit, well ahead of its time. It appeared shortly in French, German, and American editions, and has since been reprinted four times, most recently in 1968.

There is no record of any gifts to Dartmouth by Henry Thornton, but evidently he was approached at least once. In the Dartmouth Archives is a letter of August 3, 1801 from William Wilberforce to Dr. Peters, a clergyman who was soliciting help for the College in England. The letter, forwarded to John Wheelock, speaks for itself: "I have mentioned to Mr. H. Thornton and will to his brothers the want which the Society [Dartmouth College] is feeling of a chemical apparatus."

Whether Henry Thornton or his brothers made any contribution we do not know, but from a Henry Thornton letter, a copy of which is in the possession of E.M. Forster,1 we know now that he was proud of his father's role in the early history of Dartmouth. In 1812 he wrote to Hannah More, the great promoter of popular education and a fellow worker of the Clapham Sect:

A young Mr. D from America dined with me yesterday who introduced himself by a book and a letter from the President of Dartford College founded chiefly as the book related by the Earl of D and the late John Thornton. What a satisfaction it is to think of an institution containing 150 to 200 scholars in the New World now spreading its branches in that hemisphere of which a few hundred pounds opportunely given during the American War by my own Parent sustained the existence. I seem to have back the money with compound interest in the advantage of having the narrative to read to my children.

The book that John Wheelock sent to Henry Thornton was undoubtedly Memoirsof the Rev. Eleazar Wheelock, D.D., by David M'Clure, a Trustee of Dartmouth, which had appeared in 1811, but it has not been possible to identify the young Mr. D.

Henry Sykes Thornton, Henry's oldest son, had a long and successful career as partner in a leading London private bank, Williams Deacon and Co. Although he never achieved the public distinction of his father or his grandfather, he was a man in their mold, and a supporter of many humanitarian and philanthropic causes. As a student at Cambridge he roomed with another son of the Clapham Sect, Thomas Babington Macaulay, and in a spirit which John Thornton and Henry Thornton undoubtedly would have approved of, young Macaulay's father wrote to his wife that the boys' tutor had promised "to select among the thirty laundresses of Trinity College one of exemplary virtue for our youths." The friendship between the boys continued until Macaulay's death. Thornton was Macaulay's banker, and the unprecedentedly large advance royalty of £20,000 on Macaulay's History of England was deposited in Williams Bank, with a request to Thornton for "kind and most judicious counsel" on the investment of the money.

Many, descendants of John Thornton are living in England, solid citizens of standing, among them the author, E.M. Forster, whose biography of his greataunt has added so much to our knowledge of this remarkable family. From his great-aunt, Marianne Thornton, E.M. Forster inherited enough money to enable him to pursue a writing career. As he tells it, "This £8000 was the financial salvation of my life. Thanks to it, I was able to go to Cambridge... travel for a couple of years, and traveling inclined me to write ... she and no one else made my career as a writer possible."

Like Dartmouth College, he benefited by the philosophy of his Thornton ancestors, whose generosity with private wealth so enriched education. Without such money Forster might not have emerged as a leading man in English letters, and without such money Dartmouth College probably would have foundered.

1 Most surviving Thornton manuscript material is in the possession of E. M. Forster, by whose courtesy I was able to examine it at his rooms at King's College, Cambridge, in 1954. My interest in the papers was for the light they might throw on the monetary controversy in England, but a delightful by-product was the gracious hospitality of Mr. Forster. In his study, where hung a portrait of Henry Thornton, he invited me to join him in a glass of port, while he told of his visits to America, and read me some passages from the manuscript of his book on Marianne Thornton, that was soon to be published.

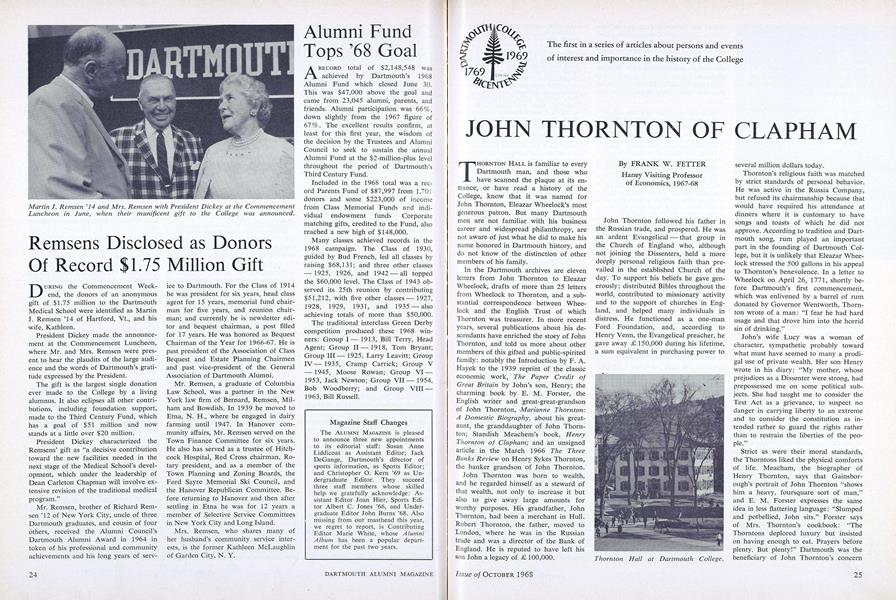

Thornton Hall at Dartmouth College.

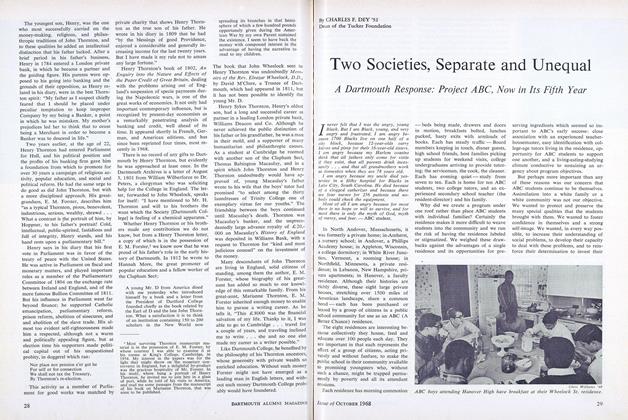

A mezzotint of John Thornton from theportrait painted by Gainsborough, 1782.

THE AUTHOR: Professor Fetter was a visiting professor at Dartmouth last year and continues to make his home in Hanover. He retired from Northwestern University, where he had been a professor of economics since 1948. A graduate of Swarthmore College, Professor Fetter received his M.A. from Princeton and his Ph.D. from Harvard. He became interested in John Thornton through his son Henry Thornton, who figured in some of Dr. Fetter's research in economic history.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTwo Societies, Separate and Unequal

October 1968 By CHARLES F. DEY '52 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

October 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

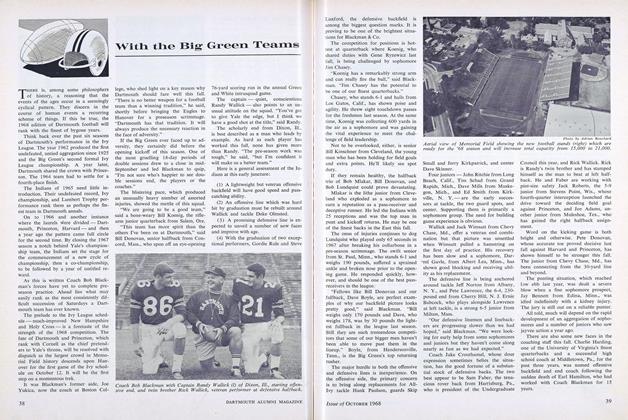

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1968 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

October 1968 By DR. STANLEY B. WELD, FLETCHER CLARK JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

October 1968 By JOHN HURD, INGHAM C. BAKER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

October 1968 By THOMAS J. SWARTZ JR., HERMAN E. MULLER JR.

Features

-

Feature

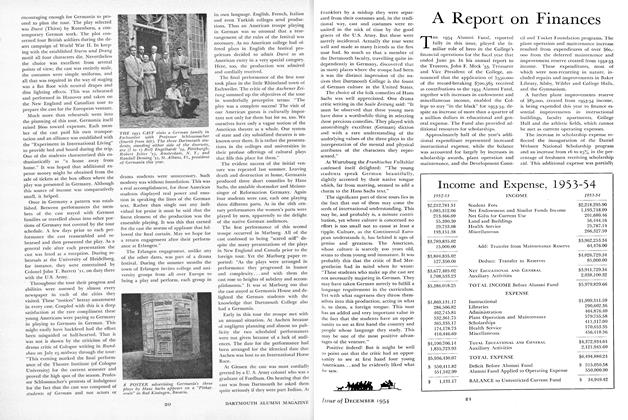

FeatureA Report on Finances

December 1954 -

Feature

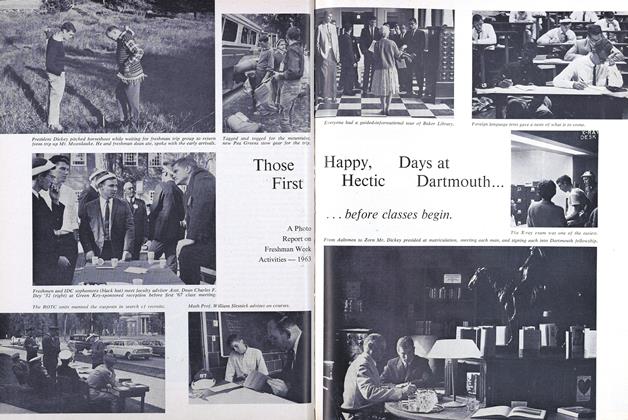

FeatureThose First Happy, Day at Hectic Dartmount

NOVEMBER 1963 -

Feature

FeatureWar Reporter

OCTOBER 1966 -

Feature

FeatureEnergy: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

April 1974 -

FEATURES

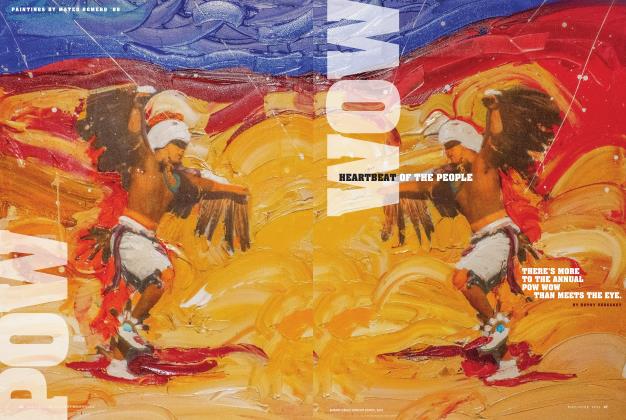

FEATURESHeartbeat of the People

MAY | JUNE 2021 By BETSY VERECKEY -

Feature

FeatureEleazar Is Outdone

OCTOBER 1970 By Charles Jay Kershner