Postcards speak in human idioms. Even at their most trivial, the messages rarely disclose innermost secrets; but they do give a flavor of the lives of ordinary people. Admittedly, some of the notes are trivial indeed. "I washed my hair yesterday and typed all the afternoon for IFR," reveals a 1946 card of Moosilauke. Other messages show a genius for compression: "Bring shawl, if cold. Went by this today. Uncle Jim married Tues. eve."

This is why I collect postcards: there is poignancy in holding a single thread of life in a plastic sheath in a binder on one's shelf. "It is beautiful up here - anyone would get well," says a woman writing from Hanover in 1946. "There is very few girls down here. I am taking my meals at the Dartmouth cafe," writes a lad concerned more about his nourishment than about his grammar.

I find my cards in shoeboxes at flea markets or in the elongated boxes of professional dealers. Even the oldest cards are not expensive, and they let me hold people's stories in the palm of my hand. "It's rather of a fast town," says J.M.R., a young woman recently arrived in White River Junction during the early 1900s. "Evenings there is any amount of Dartmouth College boys here. It is only three miles from here. Gee, some of them are swell. I began flirting with one of them before I got here, on the train."

My alma mater is the focus of many of my most prized specimens. "It's beautiful inside," says one writer of College Hall in 1908. Of Dartmouth Row, another sender wrote in 1935: "This is such a beautiful place and they want me to stay all summer, but I am not. Have no real good excuse."

A number of Hanover businesses published postcards that have found their way to my collection: Allen Drug, Coburn's Jewelry Store, the College Bookstore, the Dartmouth Bookstore, Edward P. Storrs, and E.M. Carter. Each might have ordered as many as 50,000 cards of one kind, but most orders were surely smaller.

Hanover was no vanguard of the postcard business, of course. Trade and visiting cards go back to the 17th century. Pictures of scenes, rather than simple designs, were first imprinted on writing paper in the Victorian era. Governments were won over to postcards when they discovered that cards were more profitable per pound than letters. But first, the public had to overcome a formidable barrier: mailing an exposed message.

Americans were given the chance to overcome their shyness en masse in 1898, when the United States government permitted private mailing cards. The nation rapidly entered a postcard craze that had already swamped Europe. According to American postal records, someone billion cards were mailed in the United States in 1913- about ten for every citizen.

Cards spurred entrepreneurship and technology. A 1909 illustration depicts a seller offering cards to patrons of an outdoor cafe in Berlin; strapped to his back is a letter-box for instant mailing, the revolving rack was invented for Postcards. An advertisement in the Women's Home Companion in 1907 contains this exchange: "Has this house all the modern improvements?" "Everything—here's a special closet for post cards."

The early craze died down about 1915. The quality of cards deteriorated after that time, partly because of a tariff that raised the price of cards from Germany, where the best color work was done. But the collecting never stopped. In 1956, an individual in Illinois wrote to someone in North Dakota offering to exchange five view cards at a time. One of the cards swapped showed Topliff Hall. The scene was probably meaningless to the sender, but not to me; I moved into that dormitory as a sophomore in 1958—and then bought the card from a dealer in 1984.

Dealers have proved to be my best source of cards. The professionals sort their inventory and usually protect their cards with plastic sleeves. I have found Dartmouth cards under "Colleges and Universities" and "Hanover, N.H.'' as one might expect, as well as under "Sports" and "Interiors" and "Hospitals" and "Libraries." Under the category of "Photocards," I found one identified as 20 Occom Ridge. This might be one of a kind, because it is a photograph attached to a postcard back. It cost me 25 cents.

Some dealers have an infuriating habit of claiming that a customer cleaned them out of Dartmouth cards shortly before I arrived. One dealer told me he saves his Dartmouth cards for another collector. I tried unsuccessfully to squeeze the name from him. Figuring that the other collector is an alumnus, I told him about Dartmouth camaraderie. He nodded with seeming interest. I drove home my point—that any rivalry for cards would surely be friendly. He kept the name to himself.

Now, as I thumb through a box of dealer's cards, I glance over my shoulder, not knowing whether I am a few minutes ahead of or behind a rival who may have lived across the hall from me in Topliff.

In the beginning was College Row, but the postcard depicting it was made a century later.

A western view from theTower shows the hills beyond the Green. Dealersare the best source ofDartmouth postcards.This one, of little valueoutside the College cognoscenti, cost just fourbits.

This depiction of the bustling Norwich and Hanover Railroad Station isthe author's most expensive postcard: he paid adealer $6 for it. In 1911,when it was mailed, postage cost one cent. Themessage on the back,signed by a studentnamed "Paul," couldhave been written in anyage: "Well just wrotethis to keep up the habit,but haven't anything tosay."

A Harvard man pays homage to the Indian. The artist, apparently a student, remains unidentified.

The Hanover Inn, whichacquired its name whenthe old Wheelock Hotelwas reconstructed at theturn of the century, wasa natural subject forpostcards. Its patronsoften wrote messages ofadmirable brevity. "Bringshawl, if cold," suggestedone. "Uncle Jim marriedTues. eve."

Open this card and outpop 24 miniscule views ofHanover - including theLedyard Bridge, RollinsChapel and the"new"Dartmouth Hall. In acraze that lasted from theturn of the century until1915, postcards weremailed by the billions.Enough remain for thecollector to get them for asteal.

In his postcard collection, an alumnus findsthe compressed stories of generations.

"There is a poignancy in holding asingle thread of life."

Marshall Ledger '61 is associate editor of The Pennsylvania Gazette, alumni magazine of the University of Pennsylvania.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

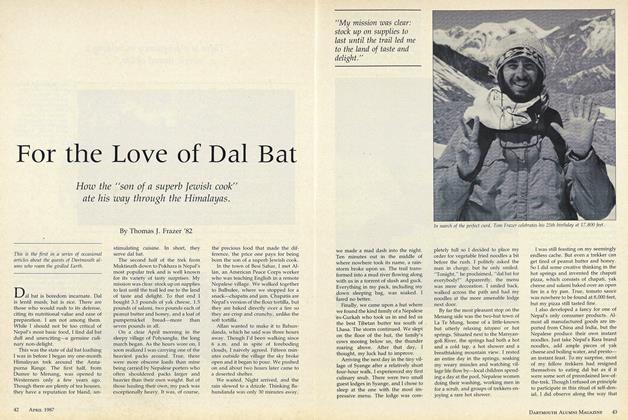

FeatureFor the Love of Dal Bat

April 1987 By Thomas J. Frazer '82 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryShould The College Change Its Tune?

April 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureThe Debate Over Safe Sex Lands Dartmouth on "Donahue"

April 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Cover Story

Cover StoryALL TOGETHER NOW ...

April 1987 -

Article

ArticleRobert Kaiser '39: Economic expertise is his planned gift to Dartmouth

April 1987 By Deborah Hodges -

Article

ArticleLeading man embraces Dartmouth; Dartmouth swoons

April 1987

Marshall Ledger '61

Features

-

Feature

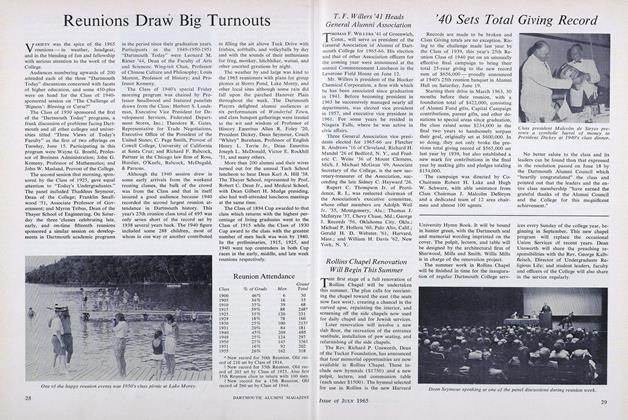

FeatureReunions Draw Big Turnouts

JULY 1965 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Rise of Research

FEBRUARY 1989 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

FeatureA VETERAN MOVES ON

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

FeatureThe Wallace Affair

JUNE 1967 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureThe Library Revolution

MAY 1968 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryI Have Come This Far

APRIL 1997 By Robert A. Bennett '93