150 years ago, on February 2, 1819, the U. S. Supreme Court handed down its historic decision preserving the College. Credit for the victory belongs to President Francis Brown as well as to Daniel Webster.

FROM 1816 to 1819, Dartmouth College fought for its life as a privately controlled institution. The attempt by the New Hampshire legislature to convert Dartmouth into a state-run university was not finally defeated until February 2, 1819, when the United States Supreme Court upheld Dartmouth's charter of 1769.

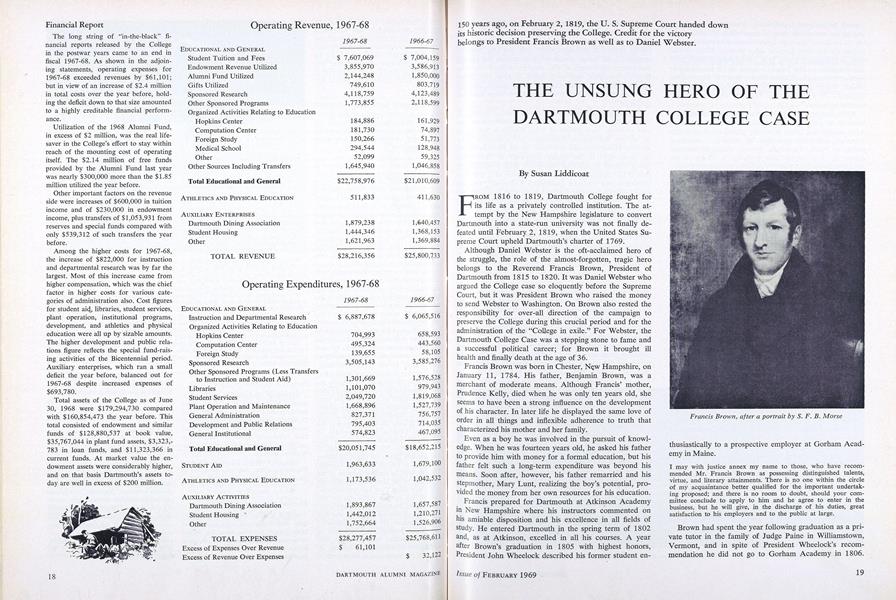

Although Daniel Webster is the oft-acclaimed hero of the struggle, the role of the almost-forgotten, tragic hero belongs to the Reverend Francis Brown, President of Dartmouth from 1815 to 1820. It was Daniel Webster who argued the College case so eloquently before the Supreme Court, but it was President Brown who raised the money to send Webster to Washington. On Brown also rested the responsibility for over-all direction of the campaign to preserve the College during this crucial period and for the administration of the "College in exile." For Webster, the Dartmouth College Case was a stepping stone to fame and a successful political career; for Brown it brought ill health and finally death at the age of 36.

Francis Brown was born in Chester, New Hampshire, on January 11, 1784. His father, Benjamin Brown, was a merchant of moderate means. Although Francis' mother, Prudence Kelly, died when he was only ten years old, she seems to have been a strong influence on the development of his character. In later life he displayed the same love of order in all things and inflexible adherence to truth that characterized his mother and her family.

Even as a boy he was involved in the pursuit of knowledge. When he was fourteen years old, he asked his father to provide him with money for a formal education, but his father felt such a long-term expenditure was beyond his means. Soon after, however, his father remarried and his stepmother, Mary Lunt, realizing the boy's potential, provided the money from her own resources for his education.

Francis prepared for Dartmouth at Atkinson Academy in New Hampshire where his instructors commented on his amiable disposition and his excellence in all fields of study. He entered Dartmouth in the spring term of 1802 and, as at Atkinson, excelled in all his courses. A year after Brown's graduation in 1805 with highest honors, President John Wheelock described his former student enthusiastically to a prospective employer at Gorha Academy in Maine.

I may with justice annex my name to those, who have recommended Mr. Francis Brown as possessing distinguished talents, virtue, and literary attainments. There is no one within the circle of my acquaintance better qualified for the important undertaking proposed; and there is no room to doubt, should your committee conclude to apply to him and he agree to enter in the business, but he will give, in the discharge of his duties, great satisfaction to his employers and to the public at large.

Brown had spent the year following graduation as a private tutor in the family of Judge Paine in Williamstown, Vermont, and in spite of President Wheelock's recommendation he did not go to Gorham Academy in 1806. Instead he accepted a position at Dartmouth as a tutor. During the next three years at the College he was known for his lucid and thorough instruction and helped gain new respect for the often-despised office of tutor. When he had been at Dartmouth but a year, Middlebury College tried unsuccessfully to hire him as a tutor, and a former classmate at Dartmouth, William Hayes, wrote to Brown from Maine: "Your fame as a tutor is spreading through New EnglandIt is said that the President and Tutor constitute the executive."

While serving as tutor, Brown studied theology and was licensed to preach by the local ministerial association. After considering offers from the church in Woodstock, Vermont, and other churches, he decided to accept a parish in North Yarmouth, Maine, where he was ordained in 1810 on his 26th birthday. A leader of the church had written to him: "You have, Sir, been frequently recommended to us as a suitable Man to supply [this] place and from the account we have had of you, we are very desirous that you should consent to come among us." The clergy of the nearby parishes also expressed their wish to have Brown as a colleague.

As a pastor, Brown more than fulfilled his congregation's expectations, and they soon became very attached to him. They were especially pleased with his marriage to Elizabeth Gilman, daughter of his deceased predecessor, on February 4, 1811. He extended his labors beyond his own parish and served as a director of the Bible, education, and missionary societies of Maine. He was elected an overseer and later a trustee of Bowdoin College and often conferred with the president on college matters. Thus he gained insight into college administration that would be helpful to him later on.

WHILE Brown was still a tutor at Dartmouth, the power struggle began between President John Wheelock and the Trustees that would culminate in the Dartmouth College Case. But both parties united in August 1810 to offer the professorship of languages at Dartmouth to Brown, not long after he had gone to Maine. After due consideration, Brown acceded to his parishioners' pleas and refused the professorship.

During the next five years, the controversy at Dartmouth grew more intense, and finally on August 26, 1815, the Trustees removed John Wheelock from the presidency and elected Francis Brown as his successor. Although he was only 31 years old and hardly a well-known figure in New England religious or educational circles, Brown had made such a favorable impression on the Trustees as a tutor that he was unanimously chosen President.

Once again the church at North Yarmouth protested Brown's leaving. In fact, at their request, an ecclesiastical council was convened made up of pastors and lay delegates from the neighboring churches to consider whether or not Brown should be released from his ministerial responsibilities. The council took note of "the extensive and growing influence and usefulness of our highly esteemed Brother in this section of the country," and how his congregation was, "to an unusual degree, attached and en- deared to their Pastor." But, on the other hand, they reviewed Brown's qualifications for the presidency of Dart- mouth at such a critical time and found "evidence, which he has exhibited, of a capacity to manage difficulties, to restore peace and harmony, where they had long been in- terrupted." All things considered, it seemed to the council that Dartmouth's need at that time for a leader such as Brown outweighed their own desire to keep him. They recommended that he be released by his church, and the way was cleared for Brown to accept the College Trustees' invitation.

Francis Brown was installed as the third President of Dartmouth on September 27, 1815. His was not an en- vied position. The defense of John Wheelock was taken up by the Jeffersonian Republican (Democratic) party in New Hampshire and was used as an issue to defeat the Federalists in the spring campaign of 1816. The newly elected Democratic legislature then proceeded to pass a law amending Dartmouth's charter of 1769. The institution was renamed Dartmouth University, and the Board of Trustees was enlarged from 12 to 21 with the new members to be appointed by Democratic Governor William Plumer. In addition, a board of overseers for Dartmouth was created, also to be appointed by the gov- ernor.

In response, the Dartmouth College Trustees, at their regular commencement meeting in August 1816, passed a resolution declaring that they did "not accept the pro- visions" of the legislature and refused "to act under the same." For his part, President Brown gave Governor Plumer the "runaround" when asked for the key to the library room so the new board could hold its meeting dur- ing commencement. Both he and the College Trustees re- fused to attend the meeting of the University board. In- stead they determined to test in court their contention that it was unconstitutional for the State of New Hampshire to violate the charter of 1769.

The Democratic legislature, in turn, at its next session passed a penal act assessing a $500 fine on anyone who performed the duties of president, trustee, or any other office of Dartmouth in defiance of the legislative acts. This new development caused consternation among the College supporters at first, but President Brown, the Trus- tees, and the two College professors, Adams and Shurtlefi, decided to stand firm. They concluded that the law was but an empty threat to scare them and would not be enforced. Time proved their assessment to be right.

And so President Brown, in defiance of the law, estab- lished a "College in exile" in makeshift quarters over the local hat store after the University officials forcibly took possession of the College buildings. The great majority of the students remained loyal to President Brown. The Uni- versity had the use of the buildings but at the most num- bered only 14 students to the College's 95. To supplement his limited teaching staff, President Brown assumed re- sponsibility for the entire instruction of the senior class and for hearing one recitation a day from the junior or sophomore classes. The broad range of his knowledge enabled him to conduct the recitations of the juniors in Tacitus, algebra, and geometry, and then review the sen- iors in the speculations of Butler, Stewart, and Edwards. A student at the College during this period, John Aiken, de- scribed President Brown's teaching technique:

For all these recitations he carefully prepared himself, so that no slipshod preparation on the part of the student should escape un- exposed. If a topic should be started or a book referred to, with which the President was not familiar, he would, by sagacious questioning, draw out what the student knew of that topic or book, and then, by his sharper analysis, his keener or more penetrating insight or his powers of broader generalization, he was prepared to discuss the subject in a way that satisfied the student, who furnished all the material, that the President under- stood the matter much better than he did himself. The mind of President Brown was eminently sagacious and comprehensive as well as discriminating.

The students had such respect for Brown that they vol- untarily obeyed the disciplinary laws of the College during this time when its officers had been stripped of all lawful authority and were acting under threat of the penal act. Appreciation of President Brown's sacrifice grew after it became known in the spring of 1817 that he had been offered the presidency of Hamilton College in New York at twice the salary he was receiving at Dartmouth. This offer gave the College Trustees and their supporters a scare, for as one friend of the College, J. W. Putnam, wrote to Brown, "the efforts of the Trustees of D.C. to have justice done them would be very materially affected by your leaving the Seminary pending the agitation of the great question." But consistent with his sense of respon- sibility, Brown chose to remain and lead the fight against the University forces.

BROWN had the chief responsibility for planning and carrying out the College's legal battle to reinstate the original charter. Essential to success was raising enough money to employ good lawyers to argue the case and to keep the College in operation now that its usual sources of revenue were cut off. The President used all his vacations from teaching to travel throughout New England speaking to alumni and other interested parties and urging their fi- nancial support of Dartmouth. One alumni response took the form of a rather unusual donation. Timothy Farrar, Class of 1807, of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, wrote en- thusiastically to Brown:

Attending an auction a few days since, I found a small cabinet, containing a pretty rare collection of South American Insects, for sale. A few of our Alumni thought it was best to save it, and we bid it off. If you should come this way in the course of the ensuing winter in a sleigh, perhaps you would think it of suffi- cient value to attempt the transportation of it to College.

Needless to say, the College needed money more than a collection of insects, however rare they might be. When his academic duties restricted Brown to Hanover, he con- tinued his fund-raising efforts by mail. For instance, on September 24, 1818, he wrote to John Bradley, a mer- chant in Maine:

The pecuniary wants of this Institution render it necessary for its constituted Guardians to apply somewhat extensively to its friends, who are favored with opulence, for aid. The College... continues to flourish in every thing connected with its internal concerns.... But we have no funds. And our suits at law and other necessary expenses render it indispensable for us to raise, by voluntary contribution, from 1500 to 2000 dollars, by January next; about one half of which is needed at the present time.... Shall you deem it consistent with your duty to afford us assistance yourself? And will you take the trouble to make application, in our behalf to some of your friends at Fryeburg?

A measure of the success of the College's money-raising efforts was the quality of the lawyers employed during the case. Some of the ablest attorneys of the day represented the College during the judicial proceedings in the New Hampshire and federal courts — Jeremiah Smith, Jere- miah Mason, Daniel Webster, and Joseph Hopkinson. But according to Mason, President Brown understood the Dart- mouth College Case so thoroughly, although he had no formal legal training, that he could have argued it as suc- cessfully as any of the lawyers. It was his thorough grasp of the details of the case that made Brown confident of a favorable outcome at the highest judicial level, even after the New Hampshire courts ruled against the College. In the spring of 1818, Daniel Webster made his famous plea be- fore the United States Supreme Court in behalf of the Col- lege. But the Court postponed its decision until the fol- lowing year.

During that period of delay, around commencement time in August 1818, Francis Brown was first troubled with a slight hoarseness, and it soon became clear that in a weak- ened condition brought on by strain and overwork, he had contracted tuberculosis. Hoping to regain his health, he traveled to the western part of New York. But even during that trip he occupied himself with College business and met with Chancellor Kent of New York, who was reputed to have some influence over several of the Supreme Court justices. The University supporters had already presented their side of the case to the Chancellor, and it seemed wise for the College to do likewise. After his visit, Brown was able to report to Webster on September 15, 1818, that Kent had been won over by the review of Webster's argument.

Brown's vacation had done little to improve his health, however, and he preached for the last time on October 6, 1818, at Thetford, Vermont. But he did not intend to give up his fund-raising activities for the College. He wrote to Webster on November 4, 1818: "I intend to make a new effort, if Providence permit, in N.H. and should be glad to know the sum necessary to be raised before you go to Washington."

It seemed that the University would try to persuade the justices to allow them to reargue the case when the session opened in February 1819. The College, therefore, also had to be prepared to reargue the case. Before leaving for Washington to attend the Court session, Webster wrote to Brown from Boston on December 17, 1818, asking him for any further information on the College situation and for his criticism of the legal argument. Webster urged Brown for the sake of his health not to come to Boston to confer, but instead to "Give me all the information you can by your pen, and let me go. Among other things, set down all the inaccuracies which you have noticed in my argument."

With the opening of the new court term on February 2, 1819, Chief Justice John Marshall immediately announced the decision in favor of Dartmouth College. Quickly Dan- iel Webster sent the good news to President Brown: "All is safe and certain. The Chief Justice delivered an opinion this morning, in our favor, on all the points.... I give you my congratulations, on this occasion...."

But even then Brown did not curtail his activities, al- though the case had been won and his disease had not abated. In March he was in Boston conferring with Daniel Webster on arrangements for printing the arguments of the College Case. By commencement that year it was ob- vious that Brown's physical condition was very serious. His friends subscribed $900 to provide the treatment that was recommended—a change of air and scene.

On October 11, 1819, President Brown and his wife set off on a trip to the South with a horse and chaise. Under the difficult traveling conditions of those days, such an extended journey would have taxed the strength of a man in good health, and that Brown survived is remarkable. After the Browns passed through New Haven, Dr. Nathan Smith, founder of the Dartmouth Medical School and then at Yale, wrote that he was "apprehensive that there must have been some insanity on the part of [Brown's] friends at Hanover or they would not have suffered him to have set out on such a forlorn hope. Those who saw the most of him here do not think that he will reach South Car- olina."

But the Browns did get as far south as Columbia, South Carolina, where they stayed from December 21 until Feb- ruary 15. According to the diary his wife kept for the trip, President Brown seemed to improve during this period, and they continued farther south to Savannah, Georgia, before starting on the long, tiring journey north. As they got closer to home, they were more and more anxious to be reunited with their family and friends in Hanover. But the weather grew increasingly warmer and took its toll of the sick man. On June 21, 1820, Mrs. Brown recorded: "Put up at half past 11 A.M. on account of extreme heat. Stopt at Mr. Woods, Lebanon only 6 miles from our be- loved home."

The following day when the students heard that Presi- dent Brown was coming, they wanted to meet him and es- cort him triumphantly into Hanover. "Though he was af- fected to tears he declined the honor saying that he had need of pall bearers rather than a triumphal procession, and was coming to his home prepared to die."

But he did wish to bid his students farewell, and he called the senior class to his sick room, and later the junior class. Then his strength failed him. On July 27, 1820, he died at the age of 36.

Thus Dartmouth was robbed of its brilliant young Presi- dent just when he could have contributed so much to the rebuilding of the College after bringing it successfully through the legal struggles of the preceding years. Not only Dartmouth, but all other chartered institutions of learning, remain in his debt for preserving the College charter from political intrusion. Perceiving his contribu- tion to their welfare, both Hamilton College and Williams College conferred honorary doctorates on President Brown in 1819.

His family carried on the work he had begun in the fields of education and religion. His son Samuel Gilman Brown, Class of 1831, was a professor at Dartmouth and later president of Hamilton College. His namesake and grandson Francis Brown, Class of 1870, was an Old Testa- ment scholar and president of Union Theological Seminary in New York City. Up to the present time, direct descend- ants of President Brown have continued to attend Dart- mouth.

The 150th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision in the Dartmouth College Case affords an occasion for a new look at the role played by President Brown in the success- ful outcome of the struggle. Daniel Webster and his fa- mous peroration, "It is, sir, a small college .. come first to mind in the story of this landmark case in United States constitutional law, but Francis Brown, that courageous and exceptional man, deserves to share honors with him. No one worked more tenaciously to achieve the victory, and no one matched the personal sacrifice he made for Dart- mouth College.

Francis Brown, after a portrait by S. F. B. Morse

The large frame house at left, later called Sanborn Hall, was where President Brown died in 1820 at the age of 36.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Bearing of the Green

February 1969 By Mary B. Ross ('38) -

Feature

FeatureA Call for Equal Opportunity

February 1969 -

Feature

FeatureA Student View of the Crisis, 1816-19

February 1969 -

Article

ArticleTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

February 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1955

February 1969 By JOSEPH D. MATHEWSON, JOHN G. DEMAS

Susan Liddicoat

Features

-

Feature

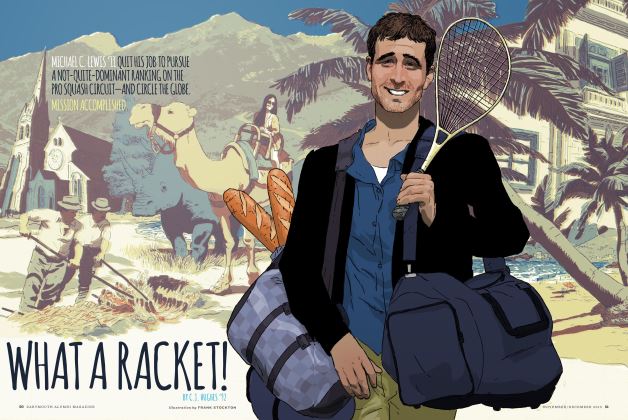

FeatureWhat a Racket!

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureThayer School Report

April 1941 By F. H. Munkelt '08 (Thayer '09) -

Feature

FeatureThe 1955 Hanover Holiday Program

April 1955 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Feature

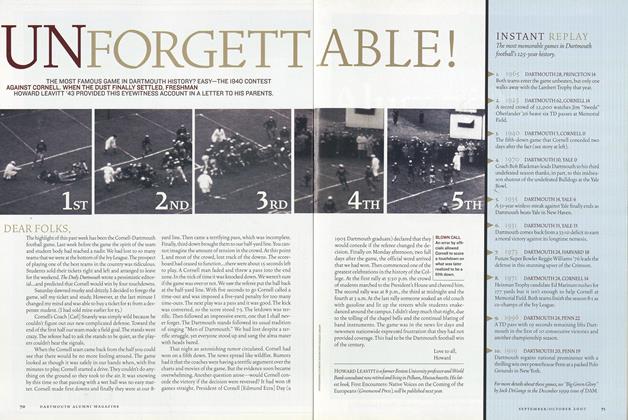

FeatureUnforgettable!

Sept/Oct 2007 By HOWARD LEAVITT ’43 -

Feature

FeatureRecommended Reading

Sept/Oct 2010 By LAUREN BOWMAN ’11 -

Feature

FeatureTau Iota Tau and Other Brassy Memories

FEBRUARY 1994 By Regina Barreca '79