THE massive ice carvings of the Dartmouth Carnival brooded above the snow-covered square that winter of 1946. The tingling air outside was matched by an atmosphere of anticipation inside the classroom. We were, for the most part, men returned from the service, eager to resume the learning process.

Through the window we could see Professor David Lambuth carefully pick his way along the frozen walk leading to the building. He was using two canes for guidance, and each had a sharp steel point which sank into the crusted surface and left a neat round hole. This first impression remains vivid because it was symbolic of his philosophy of teaching and living: make your mark as clearly and directly as possible.

That first day, in an electrifying introduction to a human being, he leaned his canes in the corner, dropped his beret on the desk, and flung his cape over a chair with a grand sweep of the arm. Then, facing the class, tears flowing down his face into his abundant beard, he intoned, first in measured Japanese Haiku, then in English:

Lo, a leaf gently falls to the ground.

He often used this classic poetic form of Japan to impress English students with the need for depth through simplicity. "Exact words for exact thoughts," he would say.

The uninitiated were misled into viewing David Lambuth as merely one of the curiosities common to all college campuses. His white suit, scraggly beard, and flowing cape gave him an aura of the absent-minded, ivory-tower professor. But those of us fortunate enough to study English under him learned of his deep complexity and sensitivity both as a man and as a teacher. Each class meeting was an encounter with excellence.

Because his knowledge of literature was vast and compelling, his students studied, analyzed, and grew to appreciate the classics of the English language. Hand outstretched he would beckon to the class to join him in understanding Conrad, Melville, Chesterton, and the Bible. "Join with them," he would say, "so that it may be said of you what Marlowe said of Lord Jim: 'He was one of us.' "

Undoubtedly it was his dramatic presentation of things well written that encouraged men to read more literature. He brought life to the written word because he saw in clear, concise language a kind of beauty. And it was his ability to transmit his affection for words that made reading exciting.

He applied his own rigid principles no less to his students than to himself. In a brief, fifty-page book, cherished by writers who seek perfection, he set forth his principles. The Golden Book on Writing, long out of print, was recently revived by a former student (S. Heagan Bayles '33) for distribution to his advertising agency. The book itself is a compendium of what we heard in class. "There is rarely more than one right word to express an idea exactly. See that you get the one right word." It was this unyielding demand for precision in writing that cut a path through the foggy thinking of many Dartmouth undergrads.

For the interested student he had constant encouragement. His range of reactions varied from kind comment to sarcastic assault on the use of unnecessary words. In a critique of one of my compositions he wrote, "I disagree with what you have to say, but you have said it well."

For all the good feeling this approval generated, it was quickly nullified on my next paper which was slashed with his proof-reader's pencil, "You move in all directions at once, like an army mule." If his remarks on student papers were sometimes stinging, the purpose was always positive.

So great was his enjoyment of a thing well said that he seemed to ache for others to join with him in understanding the exact. "Simple words for big ideas" was his way of life. When I accosted him one day after class with, "I would like to write, what do you think?", he replied with excited fervor, "Write. Write!"

In one sense Professor Lambuth's English class was a paradox. For in contrast to emphasis upon simplicity in language, he exhibited a complexity of personal feelings. His very dress and mein bespoke an intense emotionalism. And he used the full force of his fiery manner and immense intellect to lure students toward perfection in writing and thinking.

Sitting in the classroom was an appointment with the unexpected. For the range of his interests extended from criticism of the State Department (President Dickey of Dartmouth was a member of the State Department at the time) through wartime strikes, merging of the Army and Navy, integration, peacetime conscription, the moral aspects of the atomic bomb, and the Japanese art form.

What is excellence in a teacher? It is the ability to transmit to the student a concept of life so that forevermore he may draw upon it for sustenance. It is being able to convey the need to use language meaningfully. It is employing the dramatic approach to capture the imagination of the young. It is the legacy of the renaissance man who can be concerned with all mankind and more.

David Lambuth of Dartmouth came close to meeting these criteria. It was impossible to pass through his class untouched. His recriminations still sting and his compliments still glow. Now, twenty years later, the truths he uttered and the vistas he opened are as fresh and sharp as the words he loved, words that are "busy doing or making something. He showed us that striving for high goals in the exploration of the English language could be a way of life.

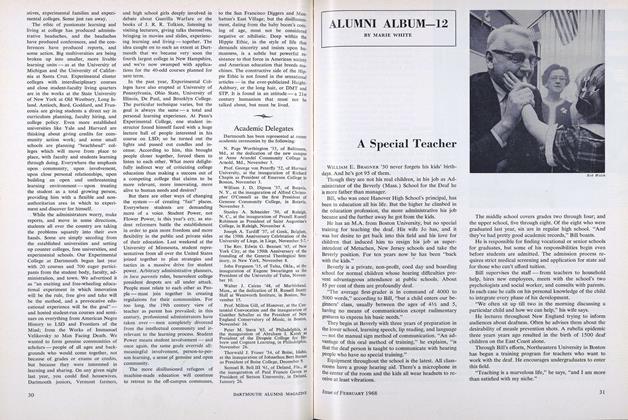

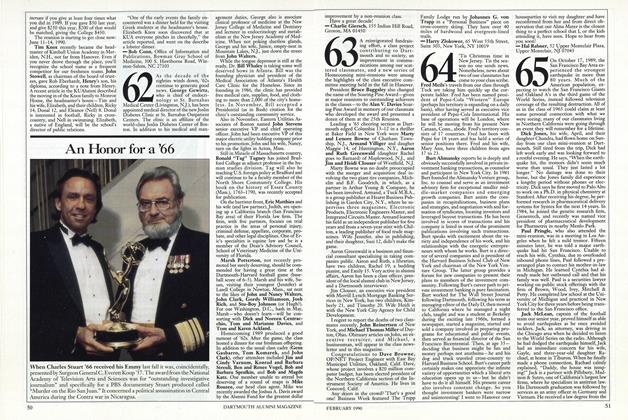

The late Prof. David Lambuth

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Classic Tradition of Judaism

February 1968 By JACOB NEUSNER -

Feature

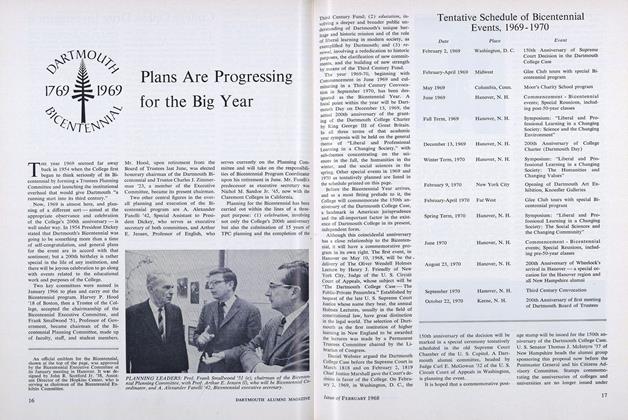

FeaturePlans Are Progressing for the Big Year

February 1968 -

Feature

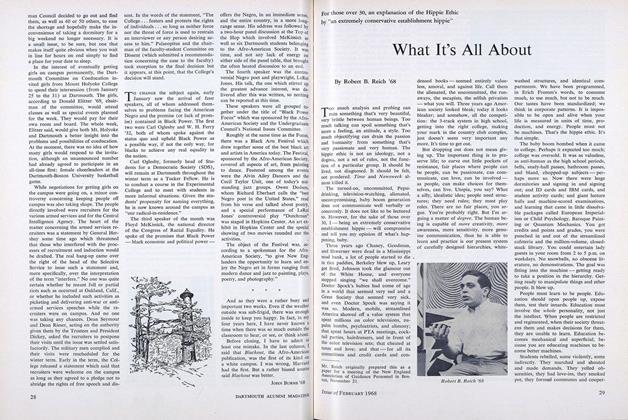

FeatureWhat It's All About

February 1968 By Robert B. Reich '68 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureNovelist on the Go

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureA Special Teacher

February 1968

Article

-

Article

ArticleNew Hampshire Surgical Club at Dartmouth

November, 1910 -

Article

ArticleThe Commencement Address

July 1947 -

Article

ArticleResigns Faculty Post

October 1947 -

Article

ArticleAn Honor for a '66

FEBRUARY 1990 -

Article

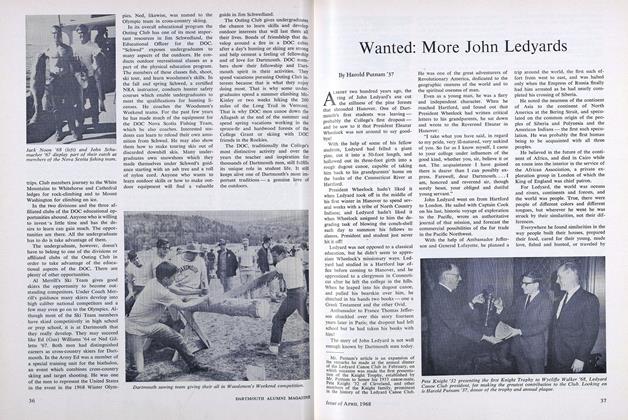

ArticleWanted: More John Ledyards

APRIL 1968 By Harold Putnam '37 -

Article

ArticleTHE THAYER SCHOOL OF CIVIL ENGINEERING

February, 1912 By Robert Fletcher