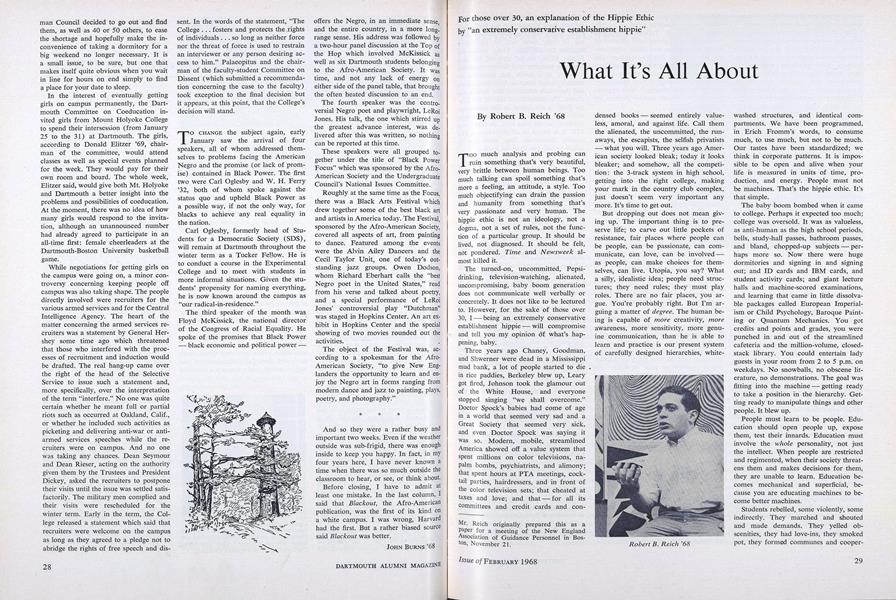

For those over 30, an explanation of the Hippie Ethic by "an extremely conservative establishment hippie"

Too much analysis and probing can ruin something that's very beautiful, very brittle between human beings. Too much talking can spoil something that's more a feeling, an attitude, a style. Too much objectifying can drain the passion and humanity from something that's very passionate and very human. The hippie ethic is not an ideology, not a dogma, not a set of rules, not the function of a particular group. It should be lived, not diagnosed. It should be felt, not pondered. Time and Newsweek almost killed it.

The turned-on, uncommitted, Pepsidrinking, television-watching, alienated, uncompromising, baby boom generation does not communicate well verbally or concretely. It does not like to be lectured to. However, for the sake of those over 30, I - being an extremely conservative establishment hippie - will compromise and tell you my opinion of what's happening, baby.

Three years ago Chaney, Goodman, and Shwerner were dead in a Mississippi mud bank, a lot of people started to die in rice paddies, Berkeley blew up, Leary got fired, Johnson took the glamour out of the White House, and everyone stopped singing "we shall overcome." Doctor Spock's babies had come of age in a world that seemed very sad and a Great Society that seemed very sick, and even Doctor Spock was saying it was so. Modern, mobile, streamlined America showed off a value system that spent millions on color televisions, napalm bombs, psychiatrists, and alimony; that spent hours at PTA meetings, cocktail parties, hairdressers, and in front of the color television sets; that cheated at taxes and love; and that - for all its committees and credit cards and condensed books - seemed entirely valueless, amoral, and against life. Call them the alienated, the uncommitted, the runaways, the escapists, the selfish privatists — what you will. Three years ago American society looked bleak; today it looks bleaker; and somehow, all the competition: the 3-track system in high school, getting into the right college, making your mark in the country club complex, just doesn't seem very important any more. It's time to get out.

But dropping out does not mean giving up. The important thing is to preserve life; to carve out little pockets of resistance, fair places where people can be people, can be passionate, can communicate, can love, can be involved - as people, can make choices for themselves, can live. Utopia, you say? What a silly, idealistic idea; people need structures; they need rules; they must play roles. There are no fair places, you argue. You're probably right. But I'm arguing a matter of degree. The human being is capable of more creativity, more awareness, more sensitivity, more genuine communication, than he is able to learn and practice is our present system of carefully designed hierarchies, whitewashed structures, and identical compartments. We have been programmed, in Erich Fromm's words, to consume much, to use much, but not to be much. Our tastes have been standardized; we think in corporate patterns. It is impossible to be open, and alive when your life is measured in units of time, production, and energy. People must not be machines. That's the hippie ethic. It's that simple.

The baby boom bombed when it came to college. Perhaps it expected too much; college was oversold. It was as valueless, as anti-human as the high school periods, bells, study-hall passes, bathroom passes, and bland, chopped-up subjects - perhaps more so. Now there were huge dormitories and signing in and signing out; and ID cards and IBM cards, and student activity cards; and giant lecture halls and machine-scored examinations, and learning that came in little dissolvable packages called European Imperialism or Child Psychology, Baroque Painting or Quantum Mechanics. You got credits and points and grades, you were punched in and out of the streamlined cafeteria and the million-volume, closedstack library. You could entertain lady guests in your room from 2 to 5 p.m. on weekdays. No snowballs, no obscene literature, no demonstrations. The goal was fitting into the machine — getting ready to take a position in the hierarchy. Getting ready to manipulate things and other people. It blew up.

People must learn to be people. Education should open people up, expose them, test their innards. Education must involve the whole personality, not just the intellect. When people are restricted and regimented, when their society threatens them and makes decisions for them, they are unable to learn. Education becomes mechanical and superficial, be- cause you are educating machines to become better machines.

Students rebelled, some violently, some indirectly. They marched and shouted and made demands. They yelled obscenities, they had love-ins, they smoked pot, they formed communes and cooperatives, experimental families and experimental colleges. Some just ran away.

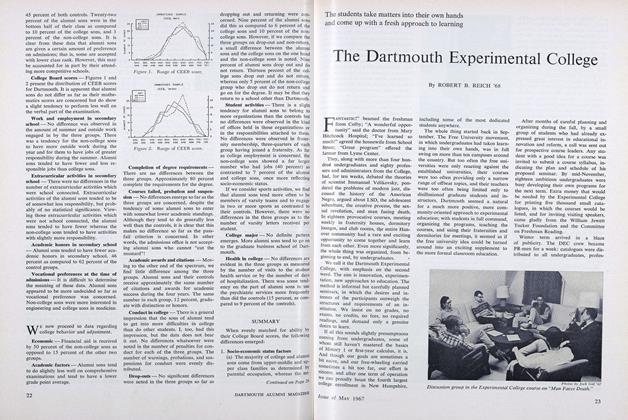

The ethic of passionate learning and living at college has produced administrative headaches, and the headaches have produced conferences, and the conferences have produced reports, and some action. Big multiversities are being broken up into smaller, more livable learning units - as at the University of Michigan and the University of California at Santa Cruz. Experimental cluster colleges with interdisciplinary courses and close student-faculty living quarters are in the works at the State University of New York at Old Westbury, Long Island. Antioch, Bard, Goddard, and Franconia are giving students a direct say in curriculum planning, faculty hiring, and college policy. Even more established universities like Yale and Harvard are thinking about giving credits for community action work; and some small schools are planning "beachhead" colleges which will move from place to place, with faculty and students learning through doing. Everywhere the emphasis upon community, upon involvement, upon close personal relationships, upon building an open and unthreatening learning environment - upon treating the student as a total growing person, providing him with a flexible and non- authoritarian area in which to experiment and discover for himself.

While the administrators worry, make reports, and move in some directions, students all over the country are taking the problems squarely into their own hands. Some are simply seceding from the established universities and setting up counter colleges, free universities, and experimental schools. Our Experimental College at Dartmouth began last year with 20 courses and 700 eager participants from the student body, faculty, administration, and town. We advertised it as "an exciting and free-wheeling educational experiment in which innovation will be the rule, free give and take will be the method, and a provocative educational experience will be the goal" - and hosted student-run courses and seminars on everything from American Negro History to LSD and Frontiers of the Mind; from the Works of Immanuel Velikovsky to Man Facing Death. We wanted to form genuine communities of scholars - people of all ages and backgrounds who would come together, not because of grades or exams or credits, but because they were interested in learning and sharing. On any given night last year, you could find housewives, Dartmouth juniors, Vermont farmers, and high school girls deeply involved in debate about Guerilla Warfare or the books of J. R. R. Tolkien, listening to visiting lecturers, giving talks themselves, bringing in movies and slides, experiencing learning and living - together. The idea caught on to such an extent at Dartmouth that we became very soon the fourth largest college in New Hampshire, and we're now swamped with applications for the 40-odd courses planned for next term.

In the past year, Experimental Colleges have also erupted at University of Pennsylvania, Ohio State, University of Illinois, De Paul, and Brooklyn College. The particular technique varies, but the goal is always the same - a total and personal learning experience. At Penn's Experimental College, one student instructor found himself faced with a huge lecture hall of people interested in his course on LSD; so he turned out the lights and passed out candles and incense. According to him, this brought people closer together, forced them to listen to each other. What more delightfully indirect way of criticizing college education than making a success out of a competing college that claims to be more relevant, more innovating, more alive to human needs and desires?

But there are other ways of changing the system — of creating "fair" places. Everywhere students are demanding more of a voice. Student Power, not Flower Power, is this year's cry, as student reformers battle the establishment in order to gain more freedom and more flexibility in the public and private sides of their education. Last weekend at the University of Minnesota, student representatives from all over the United States joined together to plan strategies and tactics in a massive drive for student power. Arbitrary administrative planners, in loco parentis rules, benevolent college president despots are all under attack. People must relate to each other as People - must join together in creating regulations for their communities. For too long, the 19th century view of teacher as parent has prevailed; in this century, professional administrators have taken over - men completely divorced from the intellectual community and irrelevant to the learning process. Student Power means student involvement - and once again, the same goals override all: meaningful involvement, person-to-person learning, a sense of genuine and open community.

The more disillusioned refugees of machine-made education will continue to retreat to the off-campus communes, to the San Francisco Diggers and Manhattan's East Village; but the disillusionment, dating from the baby boom's coming of age, must not be considered negative or nihilistic. Deep within the Hippie Ethic, in the style of life that demands sincerity and insists upon humanness, is a subtle but powerful resistance to that force in American society and American education that breeds machines. The constructive side of the Hippie Ethic is not found in the sensational articles - in the over-publicized Haight- Ashbury, or the long hair, or DMT and STP. It is found in an attitude - a 21st century humanism that must not be talked about, but must be lived.

Robert B. Reich '68

Mr. Reich originally prepared this as a paper for a meeting of the New England Association of Guidance Personnel in Boston, November 21.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Classic Tradition of Judaism

February 1968 By JACOB NEUSNER -

Feature

FeaturePlans Are Progressing for the Big Year

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureNovelist on the Go

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureA Special Teacher

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureChemical Artist

February 1968

Robert B. Reich '68

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Special Teacher

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Feature

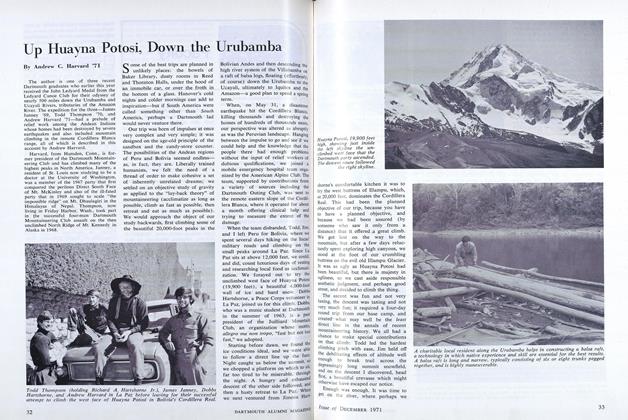

FeatureUp Huayna Potosi, Down the Urubamba

DECEMBER 1971 By Andrew C. Harvard '71 -

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

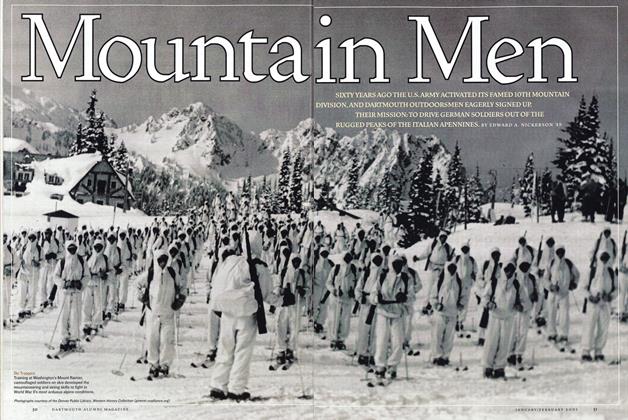

FeatureMountain Men

Jan/Feb 2001 By EDWARD A. NICKERSON ’49 -

Feature

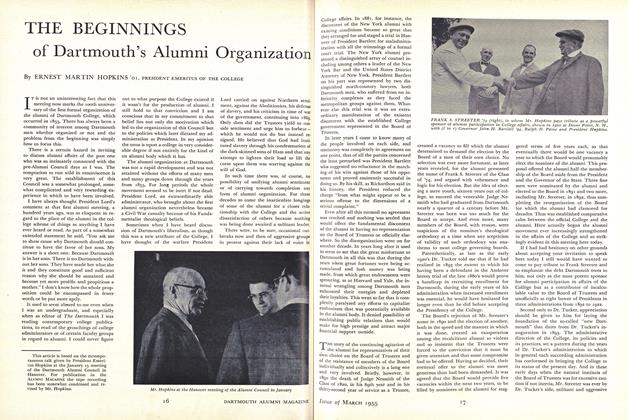

FeatureTHE BEGINNINGS of Dartmouth's Alumni Organization

March 1955 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS 01 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards Evening

October 1951 By THE HONORABLE SHERMAN ADAMS