An article drawn from one of the outstanding faculty lectures of the 1967 Alumni College

WE have touched upon five lifestyles in the Jewish tradition, which I have called the way of wisdom, the way of prophecy, the way of the intellect or of the sage, the way of philosophy, and the way of mysticism. We have considered in the eye of our imagination the values of five types of people, those represented by the literature of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, and Amos, the sayings of the rabbis, the philosophy of Maimonides, and the stories of Israel the Master of the Good Name.

These are very varied people and they stressed very varied emphases. How did they fit together? What happened to the tradition of which they were component parts? The five great traditions which we have considered came to fulfillment in a particular place and in a particular time, in the great Jewish world which took shape in Eastern Europe as the Jews were driven out of Western and Central Europe in the aftermath of the Crusades. This civilization lasted from the 10th until the 20th Century, when the Jews of Eastern Europe were almost entirely exterminated, and the rest were forced to abandon Judaism for Communism. This was a world within a whole group of worlds. There were approximately three and one-half million people in a great band between the Vistula on the West and the Russian river systems on the East. Communities in Poland, in Russia, in Rumania, and the various other countries of the East all spoke the same language, Yiddish, which was medieval German preserved and enhanced by the inclusion of Hebrew, as well as Polish and the other languages of the East. The Jew in Eastern Europe, from an external viewpoint, was like the Negro in Mississippi; perhaps in some ways his life was, if possible, more difficult. Yet that hardly mattered. These people measured themselves and their communities not by the bigotry of the world but against the standard of prophecy. They studied not what the ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF RELIGION

gentiles said but the Bible and the Talmud. They measured a man's worth in significant part by his knowledge of the classical literature. They pondered the great legal works of Maimonides. They gave birth to Hasidism.

In Lithuania the tradition laid enormous stress upon study of the Talmud, upon the learned man, the aristocracy of learning. Not everybody was involved in each and every tradition. Yet in this great mass, all the traditions came together.

It would be impossible in one lecture to characterize, even in the most general terms, Jewish civilization as it existed in Eastern Europe. I may say that the Jewish world with which you are likely to be familiar is entirely the offspring of that community, including the State of Israel, and the Jewish communities of South America, Great Britain, South Africa, Australia, as well as the U.S.A. and prewar Central and Western Europe.

We will therefore stress two themes. The first is the community as a whole, the machinery of community; and the second, somewhat more briefly, will be the Sabbath as the climax of the tradition.

The Jews were an island culture, a minority imbedded in a majority group, and yet they led their own life. They faced tremendous discriminatory legislation concerning where they might live, travel, work, the kind of work they could do. These were things which the law specified, by no means to their advantage. They lived in a situation where massacres of Jews were condoned if not actively encouraged, particularly by the Russian government. (In the past thirty years, the Communists not only closed all the institutions which preserved the culture of the Jewish people, but, in the late '30s, they killed almost every Yiddish writer, whether he was a Communist or a religious person. They completed the murders between 1948 and 1951, in Stalin's years.) And yet the Jews, had their own life. They enjoyed local autonomy. Their self-government was centered upon the synagogue, which was not only a place of study and of prayer but also their legislature, their city hall, their House of Assembly. It was there that community business was conducted. Announcements were made. All adult males would participate in elections to community offices.

Dissent was very powerful. So was individualism. Discussion generally focused upon issues rather than upon the qualities of individuals. In the synagogue any individual might come and voice a complaint or a grievance against community administration. The time set aside for complaint or dissent was during the worship service, right before the most important and dramatic moment of all, the reading of the sacred scrolls of the Torah. The Torah would be removed and it would be carried in solemn procession around the hall. Then a person who wished to make a protest could stand up, strike on the reading stand, and cry out, "I forbid the reading, you may not read the Torah."

There would follow much thumping and yelling. People would tell the man to sit down. It took courage. And the rabbi, who was the judge and the highest legal authority, would hear the man out, and dispense justice on the spot. Generally it was the force of public opinion which effected the law. Little, if any, use of physical force came to bear. Words should rule, because these are the weapons of reason and human behavior. This civilization believed, above all, that man should be reasonable. The animal - the man-animal - was a man who was not guided by reason. The man-god, the holy man, the learned man, was someone who was guided by reason. Penalties were through words. A person would be sentenced, much in the manner of Catholic penance, to pray, to say psalms, to donate to charity. The worst punishment would be ostracism. Again a punishment of words — no one would speak to him.

When time of misfortune came, people would blame it on their own sins. They would try if possible to find the guilty people and expose them. We have a quotation in the time of an epidemic: "The reason our children are dying in this epidemic is that people are not pious enough. They do not go to pray, They do not keep the laws." The massacres which came from the outside world were regarded as acts of God. No defense organization whatever existed. The people strongly believed that weapons were wrong. This was a highly pacifistic civilization. The only people who were prepared to take up weapons and fight were young people, who, in the late 19th century, had broken with the tradition of the community. They would fight. They organized little self-defense units, starting in the 1880's, which came to fruition in 1905 in self-defense organizations. This came very late in the history of this community, when it was already disintegrating. Jews were not afraid to die. They were not afraid to fight. The reason they would not fight was that they would not kill. It was a very strong prohibition.

LOCKED doors, as much as weapons, were regarded as a sin against the community. People would regard it as an affront to know that a person locked his doors. This was a social commentary people could never accept. The outside world is to be placated, and kept at a distance so that life can go on. How do you deal with the world? Not through active defense. In time of a massacre, the rabbi or the learned man was the only person who had no right to hide in the cellar. During such a time he was expected to walk out through the jeers of the peasants and to offer a bribe or a ransom for the life of the village. He would bargain on the spot for the life of the community. Often he would be killed, but to do this was part of the honor of being "the real Jew," the most honored Jew of the community.

The great authority in the end was the people. What will people say? When I say people, I don't mean "the Jewish people" as some abstraction, but "the people you live with." What will people say? What will people think? What will people do? "If you do this proscribed action, people will laugh, people will talk." People had freedom to observe and to pass judgments on their fellows. Beyond that, they had a need to communicate, to share events, to share emotions. Such stress upon seeing what other people do and upon communicating one's own ideas is inseparable from a strong feeling that individuals are responsible to one another and for one another. Collective responsibility was, to be sure, imposed by outside pressures, but these pressures combined and reinforced the basic tenets of religion. Recall Amos: The covenant at Sinai is with all the people living and dead and with each individual as well. Individually and collectively everyone is involved in the fate of the part of mankind in which he is involved. Punishment may be for personal misdeeds and it may be for an act of a group. A calamity for the group may come on account of individual sin. The merits of the community could help out also. So the central belief of Judaic civilization was that people are interdependent, not only because the act of one affects the fate of all, but also because each person needs everyone else. The underprivileged need the privileged, but the position of privilege is validated only through the sharing with those who lack. The community therefore was an extension of the family.

God was all powerful, but also, like man, reasonable. One asks Him for mercy, but demands justice. He must fulfill His promises under the covenant, just as the Jew is supposed to fulfill his duties under that same covenant. One demands mercy, that He forgive the transgressions of imperfect mortals. The worshiper therefore appealed to divine compassion precisely because he was convinced that trials and tribulations represented just punishment for transgression. In order to be pardoned one has to repent, so one finds much emphasis on penitence and upon remorse. But if punishment exceeded the crime, then the Jew would call God to justice. He would demand that He come and meet in a court of law. A Hasidic song tells of a rabbi who started a law suit against God because he had been unjust:

"Good morning to you, Lord of the universe. I Levi Isaac, the son of Sarah, have come to you on a law suit on behalf of your people Israel. What have you against your people of Israel? Why do you oppress your people Israel? I Levi Isaac, the son of Sarah, say, 'I will not stir from here. An end must be put to this. It must all stop.'" So man had the right to question God's justice, a right implied by a pact in which God and Israel are the contracting parties, indeed, a pact by now 4,000 years old. Each has his duties, each has his privileges. A profound belief held that God was a responsible, reasoning power with whom one could bargain, provided that one has lived up to his own side of the bargain. Faith in divine justice holds that in the long run, retribution for evil, reward for virtue, will come, if not necessarily in this world, then in the world to come. But preferably, here. After centuries of suffering the Almighty will do what is right. That was the faith of the community.

It is clear that the machinery of community would not work without religious faith. The machinery of the community actually was religious faith, a faith deeply imbedded in the most mundane, everyday affairs of life. And this was faith which laid great stress upon justice and mercy, covenant and atonement. Jewish tradition did not talk very much about theology. We find very few abstract sayings or treatises on the nature of God. Even Maimonides' abstractions are really a very concrete and practical affirmation. This tradition held, with Amos, that petty affairs affect the destiny of the community. This tradition held, with Proverbs, that there is a congruence between reason and nature, that the reward of right action normally is realized, and if not, there must be a reason. This tradition, in the pattern of the Talmudic Rabbi, laid its greatest stress upon wisdom, penetrating reason, thought, upon thinking about life and not responding to it thoughtlessly.

There was great trust in reason, in the mind, not only within the community but also in relationship to an irrational world.

Now in the machinery of community we have discerned the confluence of the traditions of wisdom and prophecy, ethics and law, philosophy and mysticism. How do they come together? My second cultural example is the Sabbath. The Sabbath was a day of perfect rest, when people disengaged themselves from creativity of all sorts. It was the climax of Jewish life, the climax of the week, coming every seventh day. It wove every theme of Jewish theology into the fabric of its prayers, rituals, and observances. The people lived for the Sabbath. The week was pointed toward the Sabbath. They would count the days toward the Sabbath, first day, second day, third day, not Sunday, Monday or Tuesday. It was a day of rest, but much more, of rejoicing, of fulfillment. I know no better exemplification of everything Judaic culture represented, believed in, and pointed toward, than the Sabbath. It was very unearthly. You cannot touch a day. But it was very real.

How I shall not describe what the people did, how the women would cook and bake and wash the floors; how the men prepared, took their baths and dressed up in special Sabbath garments; how the community gathered in solemn assembly. Rather I quote my teacher, Professor Abraham J. Heschel: "Judaism is a religion of time, aiming at the sanctification of time. Unlike the space-minded man to whom time is without variation and is homogeneous, to whom all hours are alike and without any special quality, the Bible senses the diversified character of time. Every hour is unique. Judaism teaches therefore that one has to be attached to holiness in time and not in space. To be attached to sacred events is to learn how to consecrate sanctuaries that emerge from the stream of a year." So Heschel teaches that the Sabbaths are the great cathedrals, the shrines of Judaism, which neither the Romans nor the Germans were able to burn. "Jewish ritual is the art of significant form in time, or of architecture working itself out through time rather than through space." Most of the life of the community, most of its observances depended upon a certain hour of the day or a season of a year. The main themes of the faith of the community lay in the realm of time. One remembers the exodus from Egypt, and he hopes for the end of days. Again Heschel: "The meaning of the Sabbath is to celebrate time rather than space. Six days a week we live under the tyranny of the things of space; on the Sabbath we try to become attuned to holiness in time. It is a day on which we are called upon to share in what is eternal in time, to turn from the results of creation to the mystery of creation, from the world of creation to the creation of the world."

So the Jew in Eastern Europe saw labor as a craft but perfect rest as an art, the result of an accord of the body, of the mind, and of the imagination. To attain excellence in an art, or in study, one has to accept the discipline of that art or that study. The seventh day has its disciplines too. It is the place in time which the community tried to build. Again Heschel: "In its atmosphere a discipline is a reminder of the adjacency of man to eternity, not necessarily through eternal truths, but perhaps in a much more concrete way. ... We often feel how poor the edifice would be if it were built exclusively of our rituals and deeds which are so awkward and often so obtrusive. How else can we express glory in the presence of eternity if not by the silence of abstaining from noisy actions."

To CONCLUDE, I speak no longer in description, but now as a participant. The essence of Jewish existence is: "life is with people." The existence of community is essential. Everything else is peripheral, an effort to reflect upon the meaning and the significance of community, of living with other human beings. This deep sense of community has survived long after the classical forms and ideas have passed away from the stage of Jewish community life. Very few of you know Jews who do fully, completely participate in the classical forms of Judaism, whether these are mediated through reform, conservative, or orthodox modes in this country. But the deep sense of community survives and flourishes.

You recall the sentence with which I began my lectures: "In the beginning God gave to every people a cup, a cup of clay, and from this cup they drank their life; they all dipped in the water but the cups were different - our cup is broken now." What was the shape of the cup of Judaism? It was the sense that the group mattered greatly. It was the belief that the group was not its own explanation, but that it existed for important reasons, that it was not simply a tribe whose existence was its own justification, but rather a community, a group which had taken shape in order to form the foundation, the vital center, of certain important truths.

The prophet and the rabbi, the philosopher and the mystic all spoke in rather parochial Jewish terms because they saw all of reality, all of the universe, to be discerned in the life of people. They were both unparochial and very parochial. They were universal for they always spoke of man. What should a man do if he sins, as in Maimonides? What is the best way for a man to live, as in the Ethics of the Fathers? This is very unparochial. But Jews were parochial in the sense that the man of whom they spoke was the Jewish human being. "Only you have I known of the families of men" is a very parochial statement. "Therefore I will visit on you all of your iniquities" is a shocking, incongruous conclusion to that kind of parochialism. The fact of being a group requires men to sense their responsibilities to God, who created all groups and all men. "If you have wrought great things in study of the Torah do not be proud on that account, for to that end you were created." Man was shaped and formed for the rational, reasonable study of revelation.

Now you will recall that I stressed the view of Ruth Benedict: Societies select from an infinite number of possibilities the few things upon which they want to build and lay the foundations of their life. Society has certain goals to which behavior is directed. I see society as tradition, as a pattern of living handed down by one generation to the next, just as the center of the Jewish tradition seems to me to be a strong sense of corporateness, or community, or society. And this dialectic of society and tradition leads to the capacity to live with cultural relativity. The sentence does not end when you say, "People who have been a minority in many times, places, cultures, know that values are relative." This is one part of the sentence. The other part of the sentence is: "Yet they have the capacity to affirm, to believe and not only to believe, but to believe that they are right."

At the outset, I quoted Ruth Benedict: "The recognition of cultural relativity carries with it its own values. It challenges customary opinions and causes those who have been bred to them acute discomfort. We must arrive at a more realistic social faith accepting as grounds of hope and as a new basis for tolerance co-existing and equally valid patterns of life which mankind has created for itself from the raw materials of existence." The Jews have a unique experience. They have a strong sense of being a group, and yet a powerful recognition of the existence and the authenticity of other groups. They could by their very being challenge the customary opinion, the accepted truths, the conventional wisdom of the majorities among whom they lived. But they searched for co-existence in society where they could continue their traditions, their patterns of behavior, their beliefs, without threatening others and without being threatened by others.

In modern times the cup seems to have broken. But I think that the cup has really been reshaped out of the old materials into a new and very different form. It would take a good many lectures to explain how the old materials have been reshaped. Rather than try to explain these things, I will end with a story.

When the Master of the Good Name had a difficult task before him he would go to a certain place in the woods. He would light a fire. He would meditate and pray and what he had set out to perform was done. A generation later, when his disciple was faced with the same awesome task he would go to the same place in the woods, and he would say, "We can no longer light the fire but we can still speak the prayers." What he wanted done became reality. A third generation passed and the next great rabbi had to perform the same solemn task. So he too went to the woods, and said, "We can no longer light a fire nor do we know the secret meditations and prayers, but we know the place in the woods, and that must be sufficient." And it was. Finally, in the next generation the leading master was called upon and he sat down in a chair in his study and he said, "We cannot light the fire. We cannot speak the prayers. We do not even know the place in the woods. But we can tell the story of how it was done." And the story had the same effect as the actions of the other three.

The story seems to have come to an end in death and in change. Yet the secret life it held can still break forth. What aspects this ancient tradition will again bring to the surface I cannot tell you. It is clear that the Jews today are like a messenger who has forgotten his message. Many of them are surely like a messenger who has forgotten that he once even had a message. And yet what God may still have in store for the Jews and for their tradition - and I for one believe there is something yet in store - that is the task not of professors but of prophets to find out.

THE AUTHOR: Professor Neusner is one of the country's leading figures in the field of Judaic studies. Two volumes of his history of the Jews in Babylonia have been published, and he has written four other books and edited two. His academic honors are numerous. A magna cum laude graduate of Harvard, he has been a Henry Fellow at Oxford University, a Fulbright Scholar at Hebrew University in Israel, a University Scholar at Columbia University, a Kent Fellow of the Society for Religion in Higher Education, a Danforth Associate, a Fellow of the American Council of Learned Societies, and a Dartmouth College Faculty Fellow. Professor Neusner came to Dartmouth as Assistant Professor of Religion in 1964. His earlier teaching posts were at the University of Wisconsin, Brandeis University, and Columbia University, where he took his Ph.D. degree in a Joint Program in Religion with Union Theological Seminary. He was recently named Associate Research Editor of the Journal of the American Academy of Religion.

The Hazleton Mirkil Reading Room for undergradute students of mathematics wasdedicated in the Bradley Mathematics Center on January 9. This memorial toProfessor Mirkil, who taught at Dartmouth for 15 years before his death last spring,contains his own library and other books and furnishings made possible by fundscontributed by colleagues, friends, and former students.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

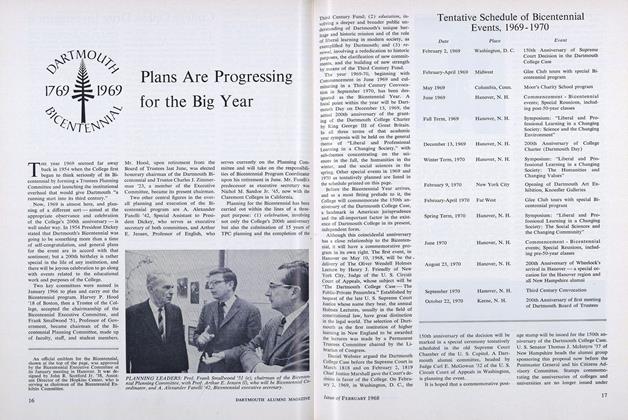

FeaturePlans Are Progressing for the Big Year

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureWhat It's All About

February 1968 By Robert B. Reich '68 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureNovelist on the Go

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureA Special Teacher

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureChemical Artist

February 1968

JACOB NEUSNER

Features

-

Feature

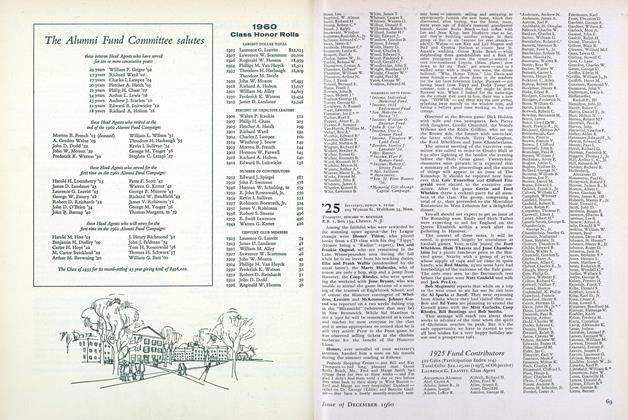

Feature1960 Class Honor Rolls

December 1960 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryExcerpts from Beverly Sills' Commencement Address

June • 1985 -

Feature

FeatureThe Widmayer Touch

OCTOBER, 1908 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureHow Do You Socialize a Freshman?

September 1993 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRobinson's Undoing

MARCH 1995 By Pam Kneisel '76 -

Feature

FeatureThe Uncompetitive Society

MAY • 1987 By Richard D. Lamm