CRISIS AT ST. JOHN'S, STRIKE AND REVOLUTION ON THE CATHOLIC CAMPUS.

APRIL 1968 AUGUSTIN-PIERRE LÉONARDCRISIS AT ST. JOHN'S, STRIKE AND REVOLUTION ON THE CATHOLIC CAMPUS. AUGUSTIN-PIERRE LÉONARD APRIL 1968

By Joseph Scimecca and Roland Damiano '62. New York: RandomHouse, 1967. 213 pp. $5.95.

On December 15, 1965, twenty faculty members of St. John's University were released from all their functions and teaching duties. The dismissal was effective immediately. Eleven more faculty members had been notified that their contracts would not be renewed after June 1966. Thus 31 teachers were disposed of in an obviously highhanded fashion. They claim that no specific charges were formulated against them and that no hearing was granted them. The dismissal was therefore a blatant violation of academic freedom. According to the administration, the action was justified because of "the appalling, vicious and irresponsible reaction" of some of the people involved.

The AAUP (American Association of University Professors) came out on the side of the faculty and insisted that such a dismissal without formal charges or hearing was "a grievous and inexcusable violation of academic freedom."

Obviously the firing which started the revolt and the strike had antecedents. About them the book under review is not particularly illuminating.

During the year 1965 the faculty (in what proportion?) demanded higher salaries and a greater share in policy-making, for instance the creation of a faculty senate. It also apparently organized on the campus The United Federation of College Teachers, which was not looked upon with benevolence by the administration. The faculty also attacked the paternalism and the arbitrariness of the, to a great extent, religious administration.

In the background two more general reasons for the unrest can be surmised. The first is the crisis induced in Catholic conservative circles by the liberalization of the Vatican Council. The new breed of Catholic intellectuals are determined in their protests against the paternalistic abuses of Churchaffiliated institutions. Though in this bitter battle, it may be doubted that the faculty took the wisest and most effective ways to solve their issues, and therefore provoked the stubbornness and resentment of a not too skilful administration.

The second broader reason for the crisis is the frequent confusion in religious or secular institutions about religious or philosophical commitments and about the standards of critical scholarship. The authors, concentrating too much on the personal issues in which they were involved, do not give us a guide to a positive scholarly education.

Visiting Professor of Religion at Dartmouth,Mr. Leonard teaches a seminar in SystematicTheology and a course studying contemporaryissues among Roman Catholic thinkers.

Books

-

Books

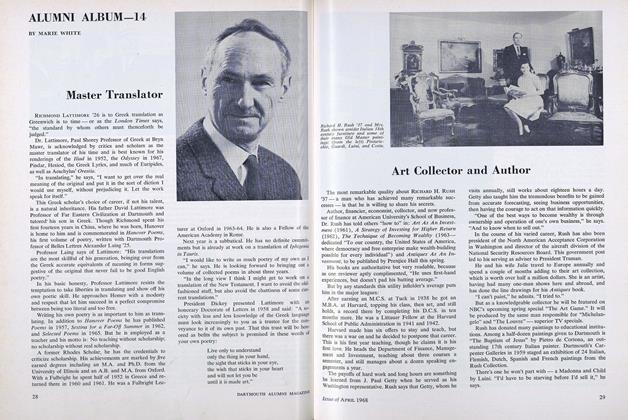

BooksFaculty Publications

February 1933 -

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

December 1956 -

Books

BooksClose Encounters

DECEMBER 1984 By Frances T. Nye, M.D -

Books

BooksWALT WHITMAN IN ENGLAND

October 1934 By Kenneth A. Robinson -

Books

BooksProselytizers and Profiteers

May 1977 By LEO SPITZER -

Books

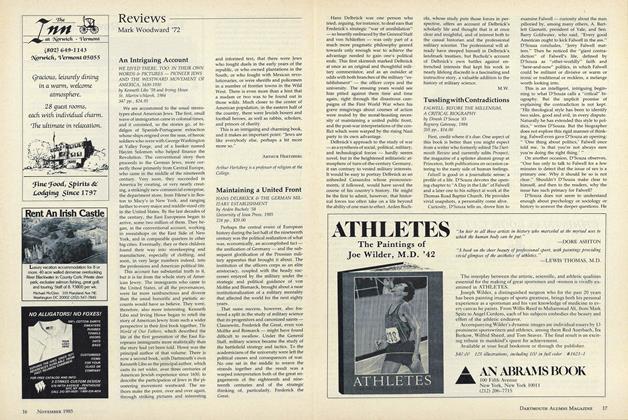

BooksMaintaining a United Front

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Mark Woodward '72