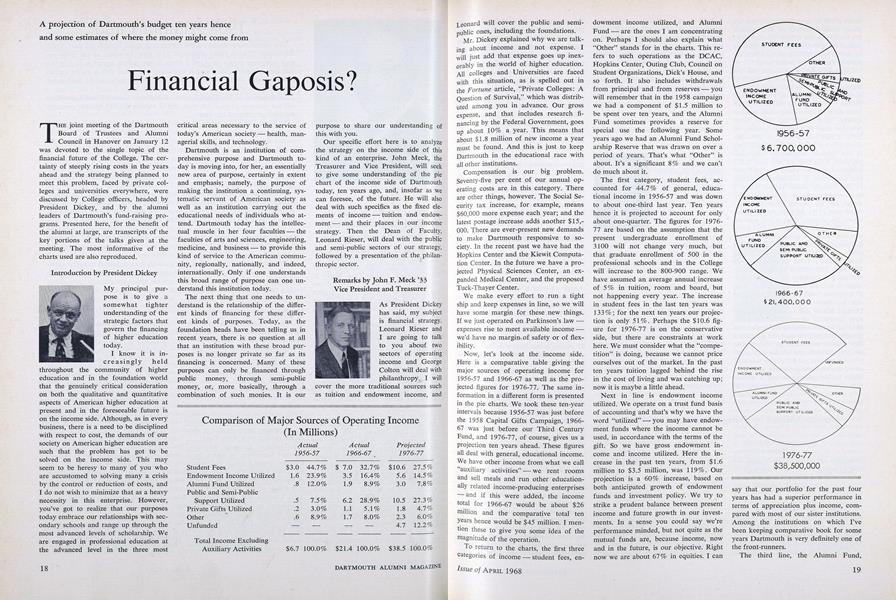

A projection of Dartmouth's budget ten years hence and some estimates of where the money might come from

THE joint meeting of the Dartmouth Board of Trustees and Alumni Council in Hanover on January 12 was devoted to the single topic of the financial future of the College. The certainty of steeply rising costs in the years ahead and the strategy being planned to meet this problem, faced by private colleges and universities everywhere, were discussed by College officers, headed by President Dickey, and by the alumni leaders of Dartmouth's fund-raising programs. Presented here, for the benefit of the alumni at large, are transcripts of the key portions of the talks given at the meeting. The most informative of the charts used are also reproduced.

Introduction by President Dickey

My principal purpose is to give a somewhat tighter understanding of the strategic factors that govern the financing of higher education today.

I know it is increasingly held throughout the community of higher education and in the foundation world that the genuinely critical consideration on both the qualitative and quantitative aspects of American higher education at present and in the foreseeable future is on the income side. Although, as in every business, there is a need to be disciplined with respect to cost, the demands of our society on American higher education are such that the problem has got to be solved on the income side. This may seem to be heresy to many of you who are accustomed to solving many a crisis by the control or reduction of costs, and I do not wish to minimize that as a heavy necessity in this enterprise. However, you've got to realize that our purposes today embrace our relationships with secondary schools and range up through the most advanced levels of scholarship. We are engaged in professional education at the advanced level in the three most critical areas necessary to the service of today's American society - health, managerial skills, and technology.

Dartmouth is an institution of comprehensive purpose and Dartmouth today is moving into, for her, an essentially new area of purpose, certainly in extent and emphasis; namely, the purpose of making the institution a continuing, systematic servant of American society as well as an institution carrying out the educational needs of individuals who attend. Dartmouth today has the intellectual muscle in her four faculties - the faculties of arts and sciences, engineering, medicine, and business — to provide this kind of service to the American community, regionally, nationally, and indeed, internationally. Only if one understands this broad range of purpose can one understand this institution today.

The next thing that one needs to understand is the relationship of the different kinds of financing for these different kinds of purposes. Today, as the foundation heads have been telling us in recent years, there is no question at all that an institution with these broad purposes is no longer private so far as its financing is concerned. Many of these purposes can only be financed through public money, through semi-public money, or, more basically, through a combination of such monies. It is our purpose to share our understanding of this with you.

Our specific effort here is to analyze the strategy on the income side of this kind of an enterprise. John Meek, the Treasurer and Vice President, will seek to give some understanding of the pie chart of the income side of Dartmouth today, ten years ago, and, insofar as we can foresee, of the future. He will also deal with such specifics as the fixed elements of income - tuition and endowment - and their places in our income strategy. Then the Dean of Faculty, Leonard Rieser, will deal with the public and semi-public sectors of our strategy, followed by a presentation of the philanthropic sector.

Remarks by John F. Meek '33 Vice President and Treasurer

As President Dickey has said, my subject is financial strategy. Leonard Rieser and I are going to talk to you about two sectors of operating income and George Colton will deal with philanthropy. I will cover the more traditional sources such as tuition and endowment income, and Leonard will cover the public and semipublic ones, including the foundations.

Mr. Dickey explained why we are talking about income and not expense. I will just add that expense goes up inexorably in the world of higher education. All colleges and Universities are faced with this situation, as is spelled out in the Fortune article, "Private Colleges: A Question of Survival," which was distributed among you in advance. Our gross expense, and that includes research financing by the Federal Government, goes up about 10% a year. This means that about $1.8 million of new income a year must be found. And this is just to keep Dartmouth in the educational race with all other institutions.

Compensation is our big problem. Seventy-five per cent of our annual operating costs are in this category. There are other things, however. The Social Security tax increase, for example, means $60,000 more expense each year; and the latest postage increase adds another $15,000. There are ever-present new demands to make Dartmouth responsive to society. In the recent past we have had the Hopkins Center and the Kiewit Computation Center. In the future we have a projected Physical Sciences Center, an expanded Medical Center, and the proposed Tuck-Thayer Center.

We make every effort to run a tight ship and keep expenses in line, so we will have some margin for these new things. If we just operated on Parkinson's law expenses rise to meet available income we'd have no margin of safety or of flexibility.

Now, let's look at the income side. Here is a comparative table giving the major sources of operating income for 1956-57 and 1966-67 as well as the projected figures for 1976-77. The same information in a different form is presented in the pie charts. We took these ten-year intervals because 1956-57 was just before the 1958 Capital Gifts Campaign, 1966-67 was just before our Third Century Fund, and 1976-77, of course, gives us a projection ten years ahead. These figures all deal with general, educational income. We have other income from what we call "auxiliary activities" — we rent rooms and sell meals and run other educationally related income-producing enterprises - and if this were added, the income total for 1966-67 would be about $26 million and the comparative total ten years hence would be $45 million. I mention these to give you some idea of the magnitude of the operation.

To return to the charts, the first three categories of income - student fees, endowment income utilized, and Alumni Fund - are the ones lam concentrating on. Perhaps I should also explain what "Other" stands for in the charts. This refers to such operations as the DCAC, Hopkins Center, Outing Club, Council on Student Organizations, Dick's House, and so forth. It also includes withdrawals from principal and from reserves you will remember that in the 1958 campaign we had a component of $1.5 million to be spent over ten years, and the Alumni Fund sometimes provides a reserve for special use the following year. Some years ago we had an Alumni Fund Scholarship Reserve that was drawn on over a period of years. That's what "Other" is about. It's a significant 8% and we can't do much about it.

The first category, student fees, accounted for 44.7% of general, educational income in 1956-57 and was down to about one-third last year. Ten years hence it is projected to account for only about one-quarter. The figures for 1976-77 are based on the assumption that the present undergraduate enrollment of 3100 will not change very much, but that graduate enrollment of 500 in the professional schools and in the College will increase to the 800-900 range. We have assumed an average annual increase of 5% in tuition, room and board, but not happening every year. The increase in student fees in the last ten years was 133%; for the next ten years our projection is only 51%. Perhaps the $10.6 figure for 1976-77 is on the conservative side, but there are constraints at work here. We must consider what the "competition" is doing, because we cannot price ourselves out of the market. In the past ten years tuition lagged behind the rise in the cost of living and was catching up; now it is maybe a little ahead.

Next in line is endowment income utilized. We operate on a trust fund basis of accounting and that's why we have the word "utilized" - you may have endowment funds where the income cannot be used, in accordance with the terms of the gift. So we have gross endowment income and income utilized. Here the increase in the past ten years, from $1.6 million to $3.5 million, was 119%. Our projection is a 60% increase, based on both anticipated growth of endowment funds and investment policy. We try to strike a prudent balance between present income and future growth in our investments. In a sense you could say we're performance minded, but not quite as the mutual funds are, because income, now and in the future, is our objective. Right now we are about 67% in equities. I can say that our portfolio for the past four years has had a superior performance in terms of appreciation plus income, compared with most of our sister institutions. Among the institutions on which I've been keeping comparative book for some years Dartmouth is very definitely one of the front-runners.

The third line, the Alumni Fund, shows a 128% increase over the past ten years, from $800,000 to $1.9 million. We have projected a 58% increase to $3 million for 1976-77, and maybe that can be said to be on the conservative side, depending on what the future holds.

Going back to the pie charts, you will notice in the third one a large wedge — representing $4.7 million or 12.2% of needed income - that is marked "Unfunded." The first three categories of income have all been going down percentagewise. Ten years ago these three provided over 80% of our income; by 1976-77 they will be down to 50%. According to our projections, to break even in our general, educational operations ten years from now we will need $38.5 million of income. There is a $4.7 million gap, which is the unfunded wedge. In the Fortune article (about which I have reservations, as you know) this wedge for the twenty institutions surveyed was 17%. At least we come out below the average. The article goes on to say that these institutions don't know where the money is coming from to cover deficits of this size. I don't think that's quite applicable to Dartmouth. If our Third Century Fund is successful, we will have $32 million of new incomeproducing endowment. By 1976-77 that ought to produce annual income of about $1.4 million. Take that out of the wedge and we have $3.3 million unfunded. Leonard Rieser and George Colton will have something to say about the possibility of further reducing the wedge, but I might add that we have the possibility that student fees could go higher, that the program of federal scholarships might revive if we ever get out of this war situation, that an expanded credit machinery might enable students to pay a greater part of the cost of their education. The starting salaries of some of our recent graduates make me wonder if there couldn't be quite a bit of growth on that side.

There is also the Alumni Fund, which we have projected conservatively, and we might do a little bit better in some of the other categories. As a last resort, we may even have to cut back on the expense total of $38.5 million if we can't finance it, but our aim is to get a balanced budget.

Remarks by Prof. Leonard M. Rieser '44 Provost and Dean of the Faculty

I will speak briefly about what we call public and semi-public funds. By this we mean funds which come to us primarily from the Federal Government and from the four major foundations, Ford, Rockefeller, Sloan, and Carnegie.

In the public sector, the principal areas from which we have had support, and can count on future support, are the National Science Foundation, the Public Health Service, including the National Institutes of Health, the Peace Corps, National Aeronautics and Space Agency, and at the present, to a certain extent, the Department of Defense.

In the past decade, 1957 to 1967, there has been a very significant growth in public funds granted to us, much more than in the semi-public funds sector. Public funds have increased from $330,000 in 1956-57 to $5.75 million in 1966-67, and semi-public funds from $170,000 to $450,000 over the same decade.

The most important thing is the nature of acquisition of public and semi-public funds. These are not resources which come to us because someone thinks we are deserving. They come in response to our making a claim which is judged on its merits by peers, particularly in the area in which the claim is made, or by very professional people in a foundation. This is the basis upon which we hold our own in this sector of public and semi-public resources.

I can't emphasize this too much because you probably do not appreciate the kind of effort it takes to get funds from, for example, the National Science Foundation, in which the judgment is made by a collection of academic people at other institutions. Funds obtained are based not only on the quality of the institution, but also on the kind of imagination and the kind of creative proposition that faculty and other members of this institution present. My presentation is based upon the confidence that we are going to be able to continue contending in this very competitive circumstance which has become much more severe than ever before.

One other observation that's pertinent here is Dartmouth's rank compared with other institutions. We are among the first twenty in terms of our endowments. Although we raise a considerable sum of money in support of purposeful objectives, we are not in the first one hundred in terms of the amount of public support we receive from federal resources. I believe the hundredth institution is the University of Alaska, which received about $7 million in the same year we received about $5 million. So, we're well below the first hundred institutions. Also, it is reasonably clear that at present there is a close correlation between the programs of the Federal Government and the level of graduate and professional education that goes on in the institutions.

The second point to make is with respect to the use to which these funds are put. In general, they are not unrestricted funds. We seek them for our purpose. The Federal Government was prepared to provide about three quarters of a million dollars for the Gilman Biology Laboratory, for example, because of the faculty who are here and the relationship between biology and medicine which we had created in the Biomedical Center. By providing it to us they didn't provide it to someone else. It wasn't our share in any sense.

On the side of semi-public resources, the Ford Foundation provided us three quarters of a million dollars to set up and operate our Comparative Studies Center. The Rockefeller Foundation has provided a significant amount of money used at present, to quite an extent, as endowment in the medical area. The Sloan Foundation has provided very significant help to the Thayer School, in the order of $2.5 million. Many engineering schools sought such help and the Foundation made its decision as to which few it would respond to. The Carnegie Corporation essentially made it possible to launch our graduate program in mathematics, with a quarter of a million dollars, and it has also supported many of our public policy studies at Dartmouth. In each case we have gone in with a proposition which reflected what we thought was an urgent need and tried to make our case.

Now, let me call your attention to the 1966-67 chart which shows how these public and semi-public funds are utilized by College activities. This will give you a sense of the problem we face in not letting the federal programs, distributed to meet public needs, decide how our institution should operate. We don't close out the Humanities but basically federal support is in Science and Technology. Maybe there will be some changes.

You will notice that there are essentially nine sectors which are fundamental sinks for money at Dartmouth. The Library and Hopkins Center, although very expensive operations, receive almost no support from either public or semi-public sources. Our hope is that we can do much better when the federal endowments for the Arts and the Humanities come into their own. The $60,000 in the Computation Center is an understatement. In that particular year we received only that much. In the "Summer Institutes and Other" the $1.5 million for 1966-67 reflects essentially the public service complement of our activities supported by public money. This means Peace Corps; it means institutes to which secondary school teachers are invited in history, arts, and language and other such programs. I suspect that this particular aspect as a public service function is going to go up.

The next line represents three divisions in the academic faculty. The Science Division received about a million dollars that year for research, instruction and other purposes, which reflects the commitment of the Federal Government to support Science and Technology. These funds included the support of study scholarships and tuition for many graduate students which allows us to provide the kind of undergraduate instruction we could not possibly provide without such resources. The Social Sciences Division has begun to show an increase in resources from the federal areas, primarily in psychology. In the Humanities, except for the semi-public money from the Ford Foundation in the Comparative Studies grant, we have almost no public resources available. This is a very serious thing because our faculty costs in Humanities are increasing significantly.

Finally, in three professional schools, we have had essentially no public resource in support of the Tuck School of Business Administration. The semi-public support you see is from the Sloan grant which provides faculty research and also some funds for a long-range study of the Tuck School program. The Thayer School has received almost $900,000 in public support and well over $100,000 from the Sloan Foundation. In the Medical School, public money supports every aspect of the medical program - research, faculty compensation, equipment, and so on.

Let me make one more observation about the Kiewit Computation Center, where you see $60,000. To emphasize my point that it's ideas that count, I want to give you the example of the Computation Center in which we are trying something which is not being tried elsewhere. It's expensive. We could operate a college without it, but we could not operate anywhere near as significant an institution without the kind of facility we have created. It's because this facility can permeate the entire institution that it's important. Although there is a small amount shown here, I estimate that in the past few years and looking to the next year or two, probably $1.75 million will have come from the Federal Government in support of the many Dartmouth-innovated ventures in computing. This is because of the ideas. These innovative procedures included a program to provide experimentation in secondary school education. The funds provided a significant contribution towards the building, and it included initially a quarter of a million dollars just in response to our proposition that we could make a better computing facility in terms of use by students, faculty, and others. So, if the ideas are good enough, there is a very close match between what we want to do and what we can get done by public-support programs.

The projection that we make, in the order of ten or eleven million dollars in ten years, is based on our assumption that we can compete in this way. When looking ahead, I come to the conclusion that funds are going to be available as they are now in terms of educational innovations. They are not going to be available just to help us meet bills. Certainly there will continue to be emphasis on graduate and professional education. The growth that we will see, and it's fortunate that our purpose and this purpose are not dissimilar, will be in terms of public service and research related to immediate public service. But the growth in long-range support for research—research which fundamentally has changed the world for better or worse—is not going to be as much, I suspect. While that will be difficult in some ways, many of our plans in terms of the opportunities available at Tuck, Thayer, and the Medical School, and in terms of the social sciences, are going to be oriented toward trying to solve some of the public problems.

Remarks by George H. Colton '35 Vice President of the College

It is quite clear, I think, from what my colleagues have presented that the definition of the task of the Development Office, as it relates to development of giving in the private sector, is to meet those cost figures that they presented as a projection; and I take it that those figures are a very large part of the wedge that John Meek has marked as Unfunded.

I have not made a prediction as to the amount of private money that we would be bringing in ten years from now. Somehow, it seems to me that it's very easy to be brave about predicting what other people are going to give at any particular time. The fact that I have not done so, however, does not reflect any lack of confidence that we can do what is necessary. The Fortune article which you were sent, and to which reference has been made, spoke of the exhaustion of alumni patience in the area of giving and also said that the colleges did not know how they were going to close these gaps. I suppose it is always possible that at some point the patience of alumni and other private donors may become exhausted, but so far the record suggests that if you have the kind of quality and the innovative ideas of which Len Rieser spoke, this is not a serious problem. In other words, so long as people see an opportunity to use their philanthropic giving to achieve a significant good, they are more than eager and willing to do it. I think it is also perfectly clear that we do have some ideas as to how these gaps are going to be met, even if we have to develop some of our conviction a bit as we go along.

As I say, I have not made predictions, but it has seemed to me that past history in this area is perhaps the best guide to what we may reasonably expect for the future. Therefore, I have devoted my charts to an analysis of what has happened over the past fifteen years. I think it gives you some base line of reference for what we may expect to do in the future. And I think I should say that whereas my colleagues, of necessity, have been talking about gifts utilized, we, of necessity, are talking about total gifts received, and this means that we are talking in part about the money that has come in for physical plant and in part about money that has come in for endowment. You cannot make a direct correlation between the figures I show you and the figures that they have just been showing.

What I believe the record shows is that over the past fifteen critical years in the growth and cost of higher education we have worked at developing the resources that were open to us, some of which we had not historically, in this institution, exploited in any way in the period before that. I think that there is clearly a great deal more to be done, more that can be done, and I think all of these resources will show considerable opportunity for growth. The second thing I think you see is that a capital campaign, instead of drying up your sources, increases your potential significantly, and I shall refer to this phenomenon in the charts themselves, but I call your attention to these two things, the development of gift resources over this fifteen year period and the marked growth all across the board that followed our last capital campaign.

Now, the first chart simply endeavors to show the total of gifts and grants from private sources over this fifteen-year span. This is largely self-explanatory as to the years and the levels achieved. I might say that the aberrant nature of some of those years comes from two things that are always somewhat unpredictable. First and foremost, Bequests. An unusually large bequest in a given year may very well shift the line happily upward. Also, sometimes, substantial foundation grants will do the same thing. You may get two or three in a given year or even one very large one that will change the pattern and, of course, the Capital Gifts Campaign in '58 particularly accounts for an unusually tall column. I think you can clearly see the steady pattern of growth, shooting across the chart, and you can see that in the years following '57-'58-'59 we clearly moved up more consistently into a higher level of support.

The second chart is a little more complicated. What we have tried to do is to show the various categories of giving on which we have specifically worked. They are not justifiable categories perhaps in any other sense, and taking them in the order in which they are listed at the top, you will notice that income trusts in '54-'55 (these are averages of two-year periods in order to smooth out the curve a little bit, and also to get it all on one chart), were almost non-existent, and yet, if you look over to last year, or several years before it, you find that this has now become a fairly substantial item, and is growing.

Corporate support in '54-'55 was even smaller. Its growth has not been spectacular, but it has certainly been steady. It has grown more conspicuously in the last couple of years when my associates have worked with people at Tuck School in developing the Tuck Associates Program. Currently our program of Associates and Partners at the Thayer School should make it grow substantially more. Foundations, really quite small in '54-'55, begin to grow substantially with the next two-year period, but not consistently. However, this is now fairly substantial. The Alumni Fund, with which you are quite familiar, with the exception of the interruption of the Capital Campaign period, has had really a rather spectacular growth, particularly following the campaign. Bequests, as you can see, are growing steadily and are assuming a very important part of the total. Then we come to Other Capital and Current Use Gifts which in some measure is a catchall. It includes a type of giving we refer to as "estate planned" gifts. It also includes, obviously, much of the money that came through the last Capital Gifts Campaign. Hopefully, there will be some very, very tall lines in that category in the years just ahead as the Third Century Fund goes on. But here is really one of our major resources as we enlist the interest and the help of individuals, particularly in all forms of major giving, whether it be for plant and facilities or endowment on an inter vivos basis.

I will close by saying that these charts provide a background for what will follow, and the rest of our discussion of giving from the private sector. I am confident that we can promote further growth in all these areas, that the innovative ideas of which Leonard Rieser spoke are certainly going to be important to our capacity to develop this kind of giving, just as it is in developing giving from the public and semi-public sectors. But, in this area, certainly in the Alumni Fund and in alumni giving for capital purposes, we have what I would assume to be our best opportunity to get that all-important unrestricted money that can be used for the bread-and-butter, on-going expenses of the institution. Clearly, if we can't get a substantial continuing flow of that kind of money, some of our foundations are going to be shaky. I believe we can do it.

Remarks by Ralph Lazarus '35 Chairman of the Alumni Fund

I don't think I need to tell you that for 53 years the Alumni Fund has been a major source of income, and for the past quarter of a century it has averaged 10% of the total College income. If you were to exclude the government grants, "auxiliary" income sources such as dormitories and dining halls, then the Alumni Fund, for ten years, has provided 12½% of the College's basic educational budget. The Fund gifts are even more important than this proportion indicates because they are unrestricted and are for current use. That's why President Dickey calls it the College's "bread and butter." We call it indispensable. The Fund has earned a reputation of being dependable. I think the growth figures which George Colton showed you indicate that. As costs have gone up, our gifts have kept pace with these increases. As prosperity has risen, so has the generosity of Dartmouth alumni.

I think all of you will agree that the Alumni Fund also keeps Dartmouth men in touch with each other through the years in ways that might not exist if we did not have this continuous communication with the College. The fellowship of Dartmouth men is now a world-wide affair. These demands, these calls to serve, the choosing of Class Agents, the exchange of telephone calls — particularly since the price went down to a dollar - and the direct mail appeals all give the feeling of a family that stays in touch with one another. I think that's an awfully important feeling in terms of the quality of the institution.

The Fund has another quality that you might describe as being infectious or contagious. What alumni themselves do in their annual giving has a tendency to affect favorably their gifts to capital campaigns. The success of the 1957-59 Capital Funds Campaign is an example. That same kind of success gave Dartmouth the courage and confidence to seek its goal of $51 million for the Third Century Fund.

This kind of experience and confidence has enabled the Fund itself to exceed $2.1 million and to seek that same amount this year as a minimum goal. You will remember that last January, at this same meeting, we made the decision that the Alumni Fund must be sustained at its present level throughout the Third Century Fund drive. I'm happy to tell you that the response to date proves that our alumni leaders, workers, and donors are behind us in this resolve. Although the Alumni Fund doesn't officially begin until April 1, we already have over $545,000 from more than 2200 alumni. We are ahead of last year by some sixty thousand dollars. However, that comes from a hundred more donors than it did last year, so maybe we shouldn't sound quite so cocky. We feel optimistic about it, although we are being a little cautious.

I'd like to say just one other thing. All of you here today have given splendid support to the Alumni Fund in this past year, and I do want to thank you for it. The strength that you have given not only to me but to the class agents, all four thousand of them who really did the work, has proven that Dartmouth can again push ahead. What has been done in the past year, we think will be done again this year.

Remarks by Rupert C. Thompson Jr. '28 Chairman of the Third Century Fund

I'll just take a minute or two to speak about our various areas of responsibility in the Third Century Fund.

First, before I ever dared assume this marvelous opportunity, I was assured that the President put the Third Century Fund first on his calendar. The most important man in this whole effort is John Dickey. He stands for Dartmouth College. He has made a record of which we are all so proud. Without his leadership, we never could get off the ground.

I am the head of the volunteer organization which has to be recruited to back this effort. This is a great privilege. I knew the President and the Trustees were behind us. That has been underscored by the marvelous work of Harvey Hood, the man who served 25 years on this Board. Harvey headed the Nucleus Fund of the Trustees and former Trustees, a fund to which each of these men has made a contribution, not the amount that I hope and trust and believe it will be when it ends up, but everyone is in the Fund. We have in it today about $5,200,000.

When we first talked of the Trustee Nucleus Fund, it seemed to me that it might be highly desirable to have an Alumni Council Nucleus Fund, but there seem to be some reasons why this is inadvisable. It's not impossible, however, and I hope Harry Dunning and I may find a way to have a Council Nucleus Fund. In any event, it is our sincere hope that every Council member, present and former, will be in the Fund by next fall when we start the upper part of alumni solicitations.

We have, today, in TCF pledges, a total of $11,854,860.83. Like all things in the world there is good and bad about that. I don't think it's bad, but I don't think it's good either. I had hoped it would be at least three or four million dollars higher than that at this time. I'm not too disappointed, though, because we only made our announcement of this campaign on September 28. There have been only very selective solicitations to date, so perhaps I am unduly impatient.

As you think of prospects, which I'm sure you are going to volunteer to take, I hope you are going to be convinced that the only type of giving which will ever obtain our objective in this campaign is completely thoughtful giving. The kind where we go in and quickly get a gift never in the world will get us off the ground. Given time, the thoughtful alumnus will evaluate his own true position and relationship to Dartmouth and will find it possible to make a gift considerably larger than anything he first considered.

Remarks by Harrison F. Dunning '30 Chairman, Major Gifts Committee Third Century Fund

I'm delighted to find this session today scheduled as a joint Trustee-Alumni Council meeting, because as I look ahead over the horizon there isn't anything in the world that could happen to Dartmouth that would be better for her than a resounding success in this $51-million Third Century Fund campaign. I'm delighted, too, with Rupe Thompson's suggestion that the members of this Council set for themselves a target of 100% participation before the general campaign opens this fall. Far from being sensitive to the interference which he anticipates with the Major Gifts Committee, I would like to be interfered with by any devoted Dartmouth man anywhere who can be helpful in this great effort.

We have fifty members on the Major Gifts Committee proper located in 35 states. We've operated on the assumption that all of the twenty or so members of the National Executive Committee, by virtue of their membership on that Committee, are part of our Major Gifts campaign team. This gives us seventy people with a prospect list of about 350. This small group of men cannot do this job all alone and we're therefore going to need further help. Of all the Dartmouth alumni, it would seem that the men who hive attended and are attending these Alumni Council meetings are more fully in tune with the Dartmouth of today and the hopes and the 'aspirations for the future than any others. Who could better represent the position and the needs of the College to our prospects than members of this Council?

I'm sure you know by now what the Major Gifts Committee is all about. It's designed to contact those members of our alumni body who might be major givers. A major gift is $100,000 and up, and I might add that the "up" is mighty important.

Fifty-one million dollars is a lot of money. I suppose we look like nit-pickers against the very ambitious program of $388 million in the next decade announced by Yale University. Well, they have their yardsticks and we have ours. I simply know that we cannot compete with our sister institutions in the Ivy League unless we keep Dartmouth in a competitive position financially and $51 million dollars just happens to be the very minimum amount that we see as our demanding needs of the next decade. And after listening to John Meek, it looks like even that isn't enough. So, failure is unthinkable, and success is mandatory. We are told that we need fifteen gifts in the million dollar class and up. We now have six of those, which means that we've got to find nine more. As of today, we have fourteen in the $100,000 and up category, where our consultants tell us that well over a hundred will be required for full success. I'm happy to tell you that just this very week three members of the Major Gifts Committee have committed themselves at the major-gift level, and now six of the fifty men working on this committee have committed themselves at the majorgift level.

Rupe Thompson mentioned that he wished our current results were several million dollars more as of today and I share that feeling with him. On the other hand, I am convinced in my own mind that the kind of money Dartmouth is asking for from its sons this time requires very thoughtful consideration in depth. It really isn't the percentage of contributors that is going to make us successful in this particular venture. That yardstick is most effective for the Alumni Fund, but in our task it is the amount of individual contributions that's going to make our success. I don't believe it is going to be hard to get something from everybody. What is going to be hard is to make sure that our Dartmouth people have raised their sights and their commitments to a level compatible with a $51-million target. This applies to me, to all of the committee members, and to every single alumnus of Dartmouth College wherever he may be. I'm sure that with full cooperation and effort on the part of everybody we are going to get it. For many of us, this can well be the major contribution of our lifetime to an institution which has meant so very much to us in our own personal lives and of which we are also very proud.

Comparison of Major Sources of Operating Income (In Millions) Actual Actual Projected1956-57 1966-67 1976-77 Student Fees $3.0 44.7% $ 7.0 32.7% $10.6 27.5% Endowment Income Utilized 1.6 23.9% 3.5 16.4% 5.6 14.5% Alumni Fund Utilized .8 12.0% 1.9 8.9% 3.0 7.8% Public and Semi-Public Support Utilized .5 7.5% 6.2 28.9% 10.5 27.3% Private Gifts Utilized .2 3.0% 1.1 5.1% 1.8 4.7% Other .6 8.9% 1.7 8.0% 2.3 6.0 % Unfunded __ __ __ __ 4.7 12.2% ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ Total Income Excluding Auxiliary Activities $6.7 100.0% $21.4 100.0% $38.5 100.0%

Income Utilized by College Activities, 1966-1967 Library and Computation Summer InstitutesHopkins Center Center and Other Public $ 13,000 $ 60,000 $1,500,000 Semi-Public 30,000 __ __ Science Social ScienceDivision Division Humanities Public $1,000,000 $200,000 $ 25,000 Semi-Public 35,000 103,000 65,000 Tuck Thayer Medical Public __ $900,000 $2,100,000 Semi-Public $ 125,000 100,000 —

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe DOC: A Learning Experience

April 1968 By Jack Noon '68 -

Feature

FeatureMaster Translator

April 1968 -

Feature

FeatureArt Collector and Author

April 1968 -

Feature

FeatureBronx County Chairman

April 1968 -

Feature

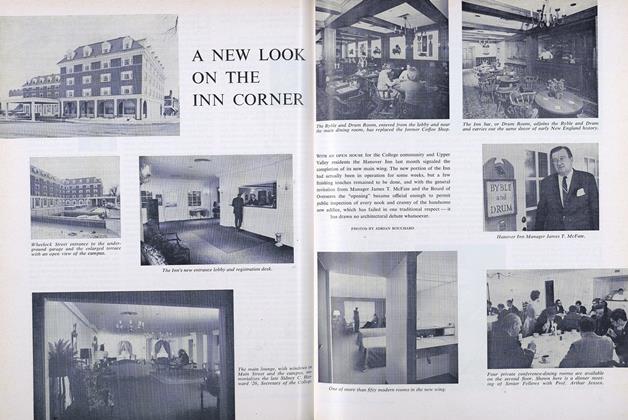

FeatureA NEW LOOK ON THE INN CORNER

April 1968 -

Article

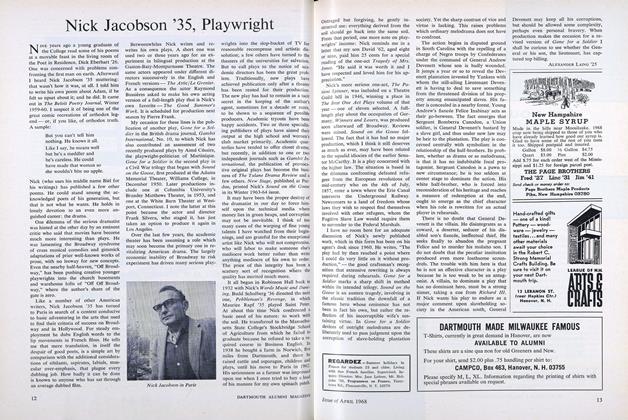

ArticleNick Jacobson '35, Playwright

April 1968 By ALEXANDER LAING '25

Features

-

Feature

Feature1960: Big, Bright, Lots of Them

October 1956 -

Cover Story

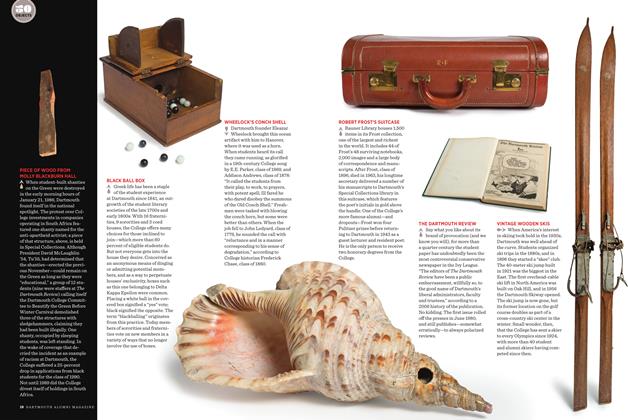

Cover StoryPIECE OF WOOD FROM MOLLY BLACKBURN HALL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureGood Teaching: A Case Study

February 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND HISTORY

FEBRUARY 1963 By LOUIS MORTON -

Cover Story

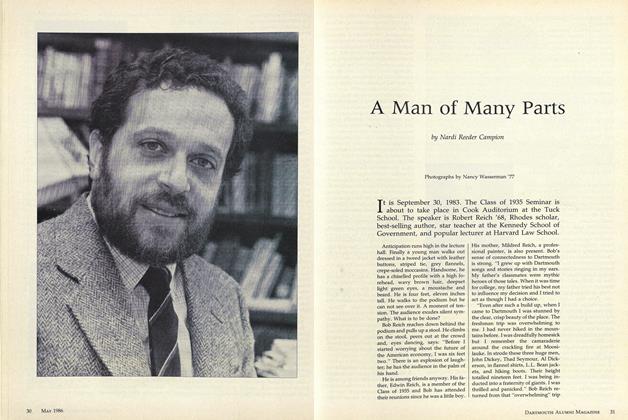

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

MAY 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

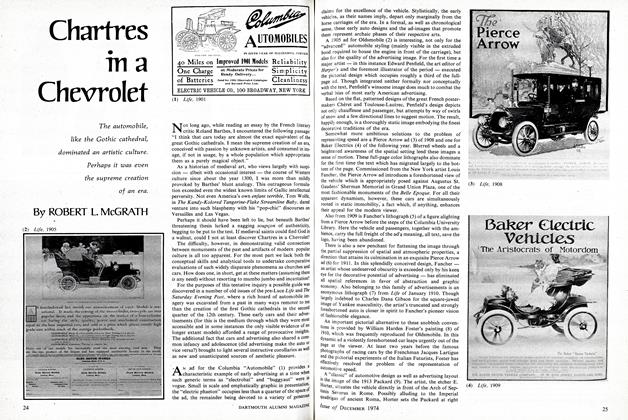

FeatureChartres in a Chevrolet

December 1974 By ROBERT L. McGRATH