ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF RUSSIAN LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE

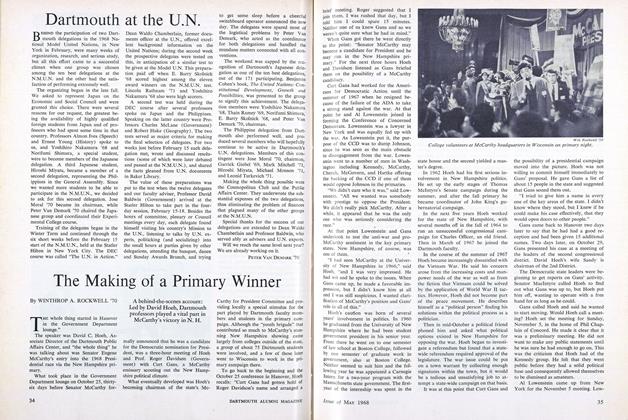

OXFORD, centrally and strategically located at the crossroads of the river and canal system, was founded in Saxon times: it was what a writer on the city's history has called "a kind of Saxon convention centre." It became a fortified medieval city, an important center of the wool industry, and a sort of second capital, almost on a par with London. Charles I used Oxford as his base in his unsuccessful struggle against the Roundheads of Cromwell. In later years the city declined in importance ' and was dominated by the colleges, which now own nearly 25 percent of the land in the city. In the past fifty years, however, the balance has been restored between town and gown, due to the influence of one man, William Morris, who built automobiles. He established Morris Garages (hence the name of the car M.G.), made a fortune, became Lord Nuffield, and even founded a college.

Oxford is now a sizable, bustling city which would be an important commercial center even if the university did not exist. The city does not, quieten down during the vacations and the streets near Carfax, the center of town, particularly Cornmarket Street, are so crowded that you cannot move along very fast whether on foot or in a car; in fact, you sometimes find as many people on the pavement as vehicles, most of them made at the Morris Motor Works at Cowley on the outskirts of the city. The traffic problem, bad enough as it is, is made even worse by the presence of innumerable bicycles. Naturally, if one is not in a car or a particular hurry, one can take a more detached, aesthetic view of the scene, and especially of the female cyclists; with the advent of the mini and micro skirts, girl-watching has become even more pleasurable in this country.

After an absence of ten years, the first thing that struck me about Oxford - apart from girls in mini skirts - was the appearance of many college buildings. College authorities have taken a leaf out of General de Gaulle's book, or rather that of his Minister of Culture, Andre Malraux (incidentally awarded an honorary doctorate here last November), and have set about cleaning off centuries of dirt and grime from many of the lovely buildings in Oxford. It is a great delight to see here, as in Paris, fine architectural monuments in something like their pristine state. One of my favorite places in Oxford has always been Radcliffe Square, where the domed Camera is flanked by All Souls, St. Mary's Church, Brasenose, and the Old Bodleian Library - all in different architectural styles. Now that these buildings have been, and are being, cleaned, they look even more beautiful when bathed in the golden sunlight of a late winter afternoon. The pale blue sky provides exactly the right backdrop for the rich glow of the buildings.

Oxford is composed of many separate colleges: 23 for men, five for women, three graduate colleges for both sexes, and All Souls College, purely a research institution, whose fellows' only obligation is to pray for the souls of those who fell in the Hundred Years War. Some colleges are old, some new, some wealthy, some poor. Christ Church has an endowment of over £300,000, some colleges really have no endowment at all. Recently the richer colleges have agreed to help the poorer so that every college will have an endowment of at least £40,000. The men's colleges are naturally older than the women's, the first of which was not founded until 1878. University College claims to have been founded in 1249, Balliol in 1263, and my own college, Merton, in 1264. There has been considerable disagreement about these dates: as I understand it, one college claims to have had the first building, another the first student, and another the first charter (nobody seems to have bothered about teachers).

The actual facts about the establishment of Oxford as a center of learning are not known; over many years King Alfred was thought responsible, quite without foundation. As close as we can get now to what happened, it appears that the process was begun around 1180 by a group of English scholars who had been expelled from Paris University after a theological dispute. The French king suffered from anglophobia: he was, as the head of a college put it here recently, the de Gaulle of his time. So it is that in international academic processions, representatives of Bologna come first, Paris second, and Oxford third in order of seniority. Ironically, the French king did England a great service, since Oxford soon far outstripped all its medieval rivals. Cambridge, by the way, was established by a group of Oxford scholars after another theological dispute, although there are some who claim that the clerics were a morose, masochistic bunch who searched until they found a place with an even unhealthier winter climate than Oxford's.

Like Dartmouth, Oxford operates with three terms (there is no summer term), but they last only eight weeks, instead of ten, which means that an undergraduate actually spends less than half the year up at Oxford. Six weeks' vacation at Christmas and Easter, as well as the long vacation of four months during the summer, allow plenty of time for travel. However, it would be wrong to think that undergraduates are free as the wind once they leave Oxford at the end of each term. In fact, nearly all have long reading lists to complete, or other projects to keep them busy, and they are tested, usually with some rigor, at the beginning of each term in examinations called "Collections." The long vacations do make for a pretty full eight weeks each term. Most students have two tutorials per week, apart from lectures, and at each of these hourly meetings they would be expected to read an essay (roughly twenty minutes in length), which is discussed and criticized by the tutor or don with a polite but firm disregard for the undergraduate's self-esteem. I am sure that Bill Todd '66, a Russian major who is now continuing his studies here and doing very well, would agree that a student is kept on his toes during the terms.

Standards are high, but of course no one wants to study every minute of the day, and there are countless extracurricular activities to keep a man away from his books. The Oxford Vade Mecum (the Latin heritage dies hard) lists a bewildering number of clubs and societies that welcome participation, from the Africa Society, Air Squadron, Alembic Club, Ballet Club, Choolant Society ("The Society meets termly for the purpose of eating choolant") to Oxymoron ("The magazine that always hits the headlines"), Spartacus (Socialist magazine), and the P. G. Wodehouse Society. Every imaginable sport is played, including tiddlywinks, and the delightful thing is that everybody has a chance to represent his college at something or other: some colleges have only about 200 members, and the largest only about 500. One thing is unforgivable at Oxford: idleness. Although it is true that undergraduates have to work hard to keep their heads above water, many do direct their energies and ambitions to extracurricular activities. The magic of Oxford is such that a graduate is not often asked what class of degree he obtained (First, Second, or Third — there was a Fourth until a few months ago) except in academic life. A recent survey of 1937 graduates showed that those earning £4,000 or more mostly took only Thirds.

The two most famous and prestigious Oxford societies are probably OUDS, the Oxford University Dramatic Society, and the Oxford Union, the university's debating society. Members of OUDS very often become highly successful professional directors and actors: for example, Richard Burton. Members of the Union, particularly its top officers, have become Prime Ministers of both political parties; these include Attlee, Eden, Macmillan (now Chancellor of the University), the present Labor Party Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, and the man who will become the next Conservative Prime Minister, Edward Heath. Winston Churchill did not attend a university, but was born at Blenheim Palace just outside Oxford. If and when a woman becomes Prime Minister, she will also probably have been an officer of the Union: women were admitted only four years ago and a woman has just been elected president. What adds extra polish and punch to the weekly debates, held on Thursday evenings, is that illustrious graduates nearly always participate on both sides of the argument. The debates are devoted to topics which are both serious and flippant: the mid-term "funny" debate last fall was on the motion "That God Is an Englishman" (it carried 433 to 270). The style of debate favors wit and whimsy, although based on a sound knowledge of the facts. I have sometimes wondered whether regular debates of this sort, of course not necessarily on the nationality of God, might not find a place at Dartmouth, especially with its excellent debating team.

Coming back to Oxford I have naturally found that life continues much as it did when I left. However, changes have been taking place; the cleaning and repairing of the college buildings that I mentioned earlier reflect an attitude that goes deeper than one might think. As a result of its age and gradual evolution over the centuries, as well as of the innate English reverence for tradition and a cult of quaintness which goes hand in hand with amateurism, Oxford has often seemed to be out of step with contemporary reality. Over the past hundred years or so there have been three reappraisals - none of them agonizing — of the university's structure and functions, in 1850, 1872, and 1922. These took the form of Royal Commissions, established by the government of the time for the express purpose of examining Oxford and making recommendations for appropriate changes. Another seemed forthcoming following the appearance of the Robbins Report of the Committee on Higher Education in 1963. It is a sign of the present atmosphere at Oxford that the university responded at once and undertook to make an internal examination of itself and set its own house in order. The reappraisal was made by the Franks Commission, a committee of seven members of the university chaired by Lord Franks, Provost of Worcester College. The members of the Commission worked with admirable despatch; they first met on April 28, 1964, took a vast amount of oral and written evidence from interested parties, and presented their report on March 26, 1966. The report consists of two volumes, the second of which is a statistical appendix.

The appearance of this Report is concrete, visible evidence that the University as a whole recognizes that times have changed and that it must change with them in order to retain its preeminence. Oxford developed over the centuries under the guidance of bachelor clerics who were lords of all they surveyed and could indulge any caprice they cared to. Once the colleges were very powerful and wealthy and the central university administration was poor. The colleges still guard their independence jealously, but the financial roles have changed: three-quarters of Oxford's income is the. university's as opposed to the colleges, and significantly three-quarters of the university's income is derived from public funds, mostly from direct grants by the government's University Grants Committee (the UGC recently announced a quinquennial grant of £32 million to Oxford for recurrent expenditures, quite a bit less than was hoped for). Even if they wished to, and I am sure the majority do not, the Oxford faculty cannot afford to ignore the demands of society as a whole; this is why they are increasingly concerned to explain the role they wish to play in the national system of education.

It is always of interest when a great university decides to undertake such a detailed examination of itself and to publish the results. In the light of recent discussions about Dartmouth's institutional Purpose, it may be worth taking a look at s°me of the things that the Franks Report has to say. The members of the Commission propose to streamline an administrative system that has worked only because of the skill and good sense of the faculty, but they stress their desire not to create a "division between the administration and the administered which Oxford has hitherto avoided." And indeed, although the Commission does propose a number of changes (it is a compliment to its members that their recommendations have been and are being acted upon with unusual speed), it leaves Oxford's essential structure and main features untouched. Oxford is and should remain a collegiate university, although this does mean that members of faculty wear two hats: they are both fellows of a college and also lecturers of the university. The fellow-lecturer has "double loyalties, joint functions, and composite remuneration."

The Commission also approves of the democratic way Oxford runs its affairs; the faculty administer themselves. The university has at its head a Chancellor; this is a ceremonial post only. The Vice-Chancellor is the real administrative head, but even this position is not permanent; it rotates every two years among heads of colleges (the Report recommends that this term be extended to four years). The Report likens the university's structure to that of the British system of government. Thus the Vice-Chancellor is Prime Minister. His Cabinet is the Hebdomadal Council — it does meet once a week, at least in term. This Council consists of six ex-officio members plus eighteen members of the faculty, elected from the Congregation, or the Parliament, that is, all the working members of the university, on the basis of one man, one vote. The Report recommends that the Hebdomadal Council operate as the executive branch of the university and be formally authorized to speak on its behalf to the outside world; up until now there had been no clear understanding on this score.

The Report recommends an increase in the faculty to improve the present student-teacher ratio of 1:13 and is concerned about the heavy burdens on the faculty which prevent them from engagductive research is linked with the question of graduate study. Oxford has been predominantly an undergraduate institution, but the Report recommends that the aim should be for graduate students to make up fully 30% of the total student body. The Report states: "We think it unlikely that Oxford can remain a major university unless this side of its work [i.e., graduate study] is expanded." The total student population should grow to 13,000 over the next fifteen to twenty years, and the proportion of women and of undergraduates studying science and social sciences needs to be increased. More undergraduates took Finals in P.P.E. (Philosophy, Politics, and Economics) last year than in any other subject. However, there might be a problem in increasing numbers in science; latest figures show an alarming decline in applications for entry by science students, not only to Oxford but all universities in England.

Members of the Commission note the casual attitude towards lectures adopted by both undergraduates and faculty, and feel that the system of lectures should be coordinated and used more rationally. What has been happening is that the tutorial has been debased, since there are too many of them and they are being used to convey information rather than teach a man how to think. The Report recommends that a wider use be made of classes, seminars, and lectures, which would then act as a complement to tutorials. Members of the Commission want tutorials to be central: "We intend that reading and writing, rather than listening, should continue to be the salient characteristic of the Oxford system."

In a sense, I suppose, Oxford represents England in microcosm, reexamining itself, reassessing its position, its aims and possibilities. Some may fear that in the process Oxford is losing confidence in itself, as well as the flair and panache that have always distinguished the university. My own feeling is that Oxford might have dwindled into quaint provincialism and mediocrity if its faculty had refused to change. The Report of the Franks Commission, which incidentally is lucidly written and a delight to read, seems to me to strike just the right note of openness to change blended with an awareness of the need to retain Oxford's special features: its administrative democracy, the collegiate system, tutorials, the emphasis on thinking rather than absorbing masses of information.

Oxford does of course offer unrivalled opportunities to the undergraduate, but this year I have been discovering that it is also an excellent place to do research. The libraries are superb, at least in my field, although I have no doubt that the cataloguing system can be puzzling to the beginner. If there is something you cannot find here, the British Museum Library is only sixty miles away. Visitors from abroad and other parts of the country are made welcome by the University Newcomers Club, which arranges meetings and excursions throughout the year, and very sensibly makes sure that wives are brought into the life of Oxford at once and are not left out in the cold. Scholars are naturally always sure of a welcome from their Oxford colleagues. I have been treated with great kindness here and am particularly grateful to the Warden and Fellows of St. Antony's College for allowing me to use their facilities and for making me a member of their Senior Common Room during my stay. I know from my conversations with him that Martin Arkowitz of the Mathematics Department, who is doing research at the Oxford Mathematical Institute, has been having an excellent year too. Even the weather has failed to dampen our enthusiasm.

Oxford's famous High Street where it divides Queens and University Colleges.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Making of a Primary Winner

May 1968 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Alumni Relations

May 1968 -

Feature

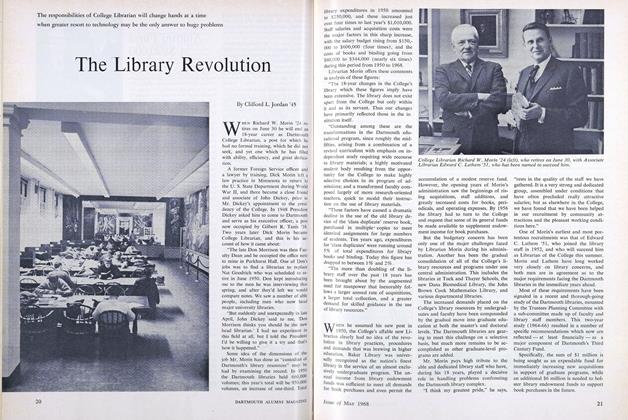

FeatureThe Library Revolution

May 1968 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

May 1968 By EARL H. COTTON, ROBERT G. THOMAS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

May 1968 By JILDO CAPPIO, ALBERT C. BONCUTTER

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT NICHOLS' SPEECH AT CLARK COLLEGE

February, 1910 -

Article

ArticleCANOE DROPOUT

Jan/Feb 2006 By Bill Gifford '88 -

Article

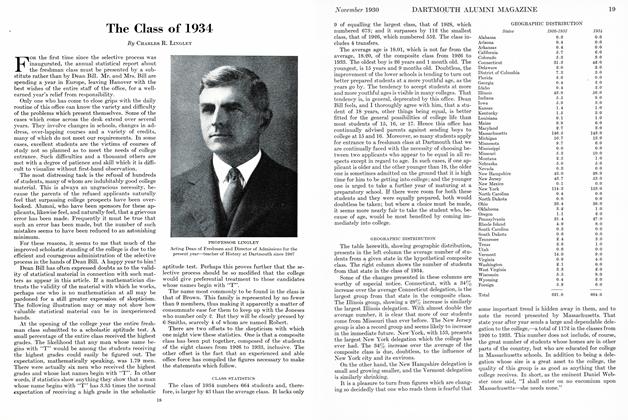

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November, 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

October 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleAlumni News

Nov/Dec 2006 By Lisa Sylvester '93 -

Article

ArticleThe Battle Against AIDS

FEBRUARY 1989 By Martha Hennessey '76