A behind-the-scenes account: Led by David Hoeh, Dartmouth professors played a vital part in McCarthy's victory in N. H.

THE whole thing started in Hanover in the Government Department lounge."

The speaker was David C. Hoeh, Associate Director of the Dartmouth Public Affairs Center, and "the whole thing" he was talking about was Senator Eugene McCarthy's entry into the 1968 Presidential race via the New Hampshire primary.

What took place in the Government Department lounge on October 25, thirtysix days before Senator McCarthy formally announced that he was a candidate for the Democratic nomination for President, was a three-hour meeting of Hoeh and Prof. Roger Davidson (Government) with Curt Gans, a McCarthy emissary scouting out the New Hampshire political climate.

What eventually developed was Hoeh's becoming chairman of the state's McCarthy for President Committee and providing locally a special stimulus for the part played by Dartmouth faculty members and students in the primary campaign. Although the "youth brigade" that contributed so much to McCarthy's stunning New Hampshire showing came largely from colleges outside of the state, a group of about 75 Dartmouth students were involved, and a few of these later went to Wisconsin to work in the primary campaign there.

To go back to the beginning and the October 25 conference in Hanover, Hoeh recalls: "Curt Gans had gotten hold of Roger Davidson's name and arranged a brief meeting. Roger suggested that I join them. I was rushed that day, but I told him I could spare 15 minutes. Neither one of us knew Gans and so we weren't quite sure what he had in mind."

When Gans got there he went directly to the point: "Senator McCarthy may become a candidate for President and he may run in the New Hampshire primary." For the next three hours Hoeh and Davidson listened as Gans briefed them on the possibility of a McCarthy candidacy.

Curt Gans had worked for the Americans for Democratic Action until the summer of 1967 when he resigned because of the failure of the ADA to take a strong stand against the war. At that point he and Al Lowenstein joined in forming the Conference of Concerned Democrats. Lowenstein was a lawyer in New York and was equally fed up with the war. As Lowenstein put it, the purpose of the CCD was to dump Johnson, since he was seen as the main obstacle to disengagement from the war. Lowenstein went to a number of men in Washington including Kennedy, McCarthy, Church, McGovern, and Hartke offering the backing of the CCD if one of them would oppose Johnson in the primaries.

"We didn't care who it was," said Lowenstein. "All we wanted was somebody with prestige to oppose the President. We didn't really pick McCarthy. After a while, it appeared that he was the only one who was seriously considering the race."

At that point Lowenstein and Gans undertook to test the anti-war and pro-McCarthy sentiment in the key primary states. New Hampshire, of course, was one of them.

"I had seen McCarthy at the University of New Hampshire in 1966," said Hoeh, "and I was very impressed. He had wit and he spoke to the issues. When Gans came up, he made a favorable impression, but I didn't know him at all and I was still suspicious. I wanted clarification of McCarthy's position and Gans' role in all of this."

Hoeh's caution was born of several years' involvement in politics. In 1960 he graduated from the University of New Hampshire where he had been student government president in his senior year. From there he went on to one semester of law school at Boston College, followed by one semester of graduate work in government, also at Boston College. Neither seemed to suit him and the following year he was appointed a Carnegie Intern for a two-year program with the Massachusetts state government. The firstyear of the internship was spent in the state house and the second yielded a master's degree.

In 1962 Hoeh had his first serious involvement in New Hampshire politics. He set up the early stages of Thomas Mclntyre's Senate campaign during the summer, and after the fall primary he became coordinator of John King's gubernatorial campaign.

In the next five years Hoeh worked for the state of New Hampshire, with several months off in the fall of 1964 to ran an unsuccessful congressional campaign for Charles Officer, an old friend. Then in March of 1967 he joined the Dartmouth faculty.

In the course of the summer of 1967 Hoeh became increasingly dissatisfied with the Vietnam War. He said his concern arose from the increasing costs and manpower needs of the war as well as from the fiction that Vietnam could be solved by the application of World War II tactics. However, Hoeh did not become part of the peace movement. He describes himself as a "political person" finding his solutions within the political process as a politician.

Then in mid-October a political friend phoned him and asked what political options existed in New Hampshire for opposing the war. Hoeh began to investigate a referendum but found that a statewide referendum required approval of the legislature. The war issue could be put on a town warrant by collecting enough signatures within the town, but it would be a tedious and unsatisfying job to attempt a state-wide campaign on that basis.

It was at this point that Curt Gans and the possibility of a presidential campaign moved into the picture. Hoeh was not willing to commit himself immediately to Gans' proposal. He gave Gans a list of about 15 people in the state and suggested that Gans sound them out.

"I tried to give him a name in every one of the key areas of the state. I didn't know where they stood, but I knew if he could make his case effectively, that they would open doors to other people."

Gans came back to Hanover two days later to say that he had had a good reception and had been given 15 additional names. Two days later, on October 29, Gans presented his case at a meeting of the leaders of the second congressional district. David Hoeh's wife Sandy is chairman of the 2nd District.

The Democratic state leaders were beginning to get reports on Gans' activity. Senator Maclntyre called Hoeh to find out what Gans was up to, but Hoeh put him off, wanting to operate with a free hand for as long as he could.

Gans called Hoeh and said he wanted to start moving. Would Hoeh call a meeting? Hoeh set the meeting for Sunday, November 5, in the home of Phil Chaplain of Concord. He made it clear that it was a preliminary meeting. He did not want to make any public statements until he was sure he had enough to go on. This was the criticism that Hoeh had of the Kennedy group. He felt that they went public before they had a solid political base and consequently allowed themselves to be dismissed as amateurs.

A 1 Lowenstein came up from New York for the November 5 meeting. Lowenstein told the group that they could affect the course of history. He was clear and forthright, and he was enthusiastic.

Hoeh felt that Lowenstein's pitch was perfect for the New Hampshire group. "He spoke in terms of politics ... how we could use the political system to oppose Johnson and the war. This registered and meant something to us in New Hampshire. We were political people and we wanted to hear someone talk in political terms."

The group that gathered in Concord still had some doubts. They wanted to think about it some more. Another meeting was scheduled for Sunday, October 19.

On the afternoon of the 19th the Democratic State Committee met in Concord to endorse LBJ. Teddy Kennedy had been invited to the meeting in the hope that he would endorse the President for reelection. His speech was less than a ringing endorsement. He talked more about his brother than the President and at one point told the group, "Robert Kennedy is not a candidate for a write-in in New Hampshire. That's spelled R-O-B-E-R-T."

Robert Kennedy, himself, had said only a short time earlier that he welcomed McCarthy as a possible candidate and that he would stay neutral. Hoeh reminded the state committee of Bobby's position, but they endorsed Johnson by a vote of 23 to 5.

That night Hoeh's informal group formed a steering committee with Hoeh as chairman. "I thought you might do this," said Lowenstein, who had come up for the meeting, and he dumped a bag of "McCarthy for President" buttons on the table. On Tuesday Hoeh held a news conference in Concord to announce the formation of the McCarthy group.

The Conference of Concerned Democrats was holding a meeting in Chicago on December 2 and 3. Lowenstein urged the New Hampshire group to go. Six of them, including Sandy and David Hoeh, went to the conference. When they got to Chicago, McCarthy had just announced that he would oppose the President in California, Oregon, Wisconsin, Nebraska and perhaps Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Hoeh met with McCarthy in Chicago and tried to impress upon him the importance of the New Hampshire primary.

"If you come to New Hampshire," Hoeh told him, "you will have to spend considerable time and you will have to campaign hard, but the results will be there." McCarthy was still not convinced and went back to Washington saying only that he would think about it.

On December 14 McCarthy himself came to New Hampshire to test the political atmosphere. The result was less than encouraging. A crowd of 2000 gathered in Manchester on the evening of December 14 to hear McCarthy rouse them to action. But McCarthy's speech was dry and somewhat dull. He wasn't using the phrases that he developed later in the Wisconsin and Indiana campaigns. The audience had expected too much from him and they were disappointed. Later that evening Hoeh brought McCarthy to a private gathering of about 60 New Hampshire politicians.

"This looks like a government in exile," said McCarthy as he walked into the room. Dave Hoeh seated McCarthy in front of the group.

"Senator," said Hoeh, "we had a. chance to hear you. Now we want to tell you what we can do for you here in New Hampshire." McCarthy listened as Hoeh went around the room asking both the optimists and the pessimists of the group to evaluate McCarthy's chances in the state. McCarthy was impressed. He told them that he thought he had better leave before they convinced him to do something rash.

The next three weeks were McCarthy's time for decision about New Hampshire. During that time Hoeh, Gerry Studds, and others prepared some statistical material which, according to Hoeh, turned out to be the basic strategy of the campaign. It outlined a tentative 12-day New Hampshire campaign schedule according different priorities to various areas of the state. It had originally been thought that McCarthy would need as much as 21 campaign days in New Hampshire but in late December it appeared that McCarthy had become so much of a national figure that 12 days would be enough. (McCarthy eventually spent 20 campaign days in the state.)

During the three weeks between McCarthy's Manchester speech and his entry in New Hampshire the press suggested that if he backed away from New Hampshire, he would not be able to call himself a serious candidate. During that time the ADA voted to support McCarthy, although not without a great deal of internal dissension among the group itself. Another event forced McCarthy toward an open bid in the March 12 New Hampshire primary. New Hampshire Attorney General George Papagianis had given an advisory opinion banning the expenditure of funds on behalf of a candidate without the candidate's public consent. If anything was going to be done in New Hampshire, McCarthy would have to declare. (This opinion was later thrown out by the New Hampshire Supreme Court, but in the meantime the McCarthy people had to work on the assumption that, for a campaign to be waged, McCarthy would have to declare.)

On New Year's Eve, Blair Clark, McCarthy's national campaign manager, called Hoeh from Washington to say that he wanted to come up the next day and meet with the steering committee. Hoeh told Clark that he could have a meeting on the 2nd. Clark arrived and advised the committee that a decision would be made within 48 hours. He said he was looking over the New Hampshire organization. On the evening of the 2nd, Hoeh and Blair ate dinner together in the dining room of the Sheraton Wayfarer in Manchester. Near the cashier's desk in the main dining room is a house telephone. While Hoeh and Clark were eating the phone rang and a waitress signaled to Hoeh. It was McCarthy.

"I'm coming in."

"Can I announce it?" asked Hoeh.

"Yes, hold a press conference tomorrow and I'll hold one here in Washington on Thursday."

Later that evening the steering committee met again. Clark told them what he thought was needed.

"We realized what a job the campaign would be, "remarked Hoeh, "but we had experienced people. Clark was reassured by our comittee. We were not a CCD or a peace group but a McCarthy group, and we were unified."

On January 3 the New Hampshire McCarthy movement became public property. David Hoeh and his wife Sandy continued their work, but they were no longer alone. In the Dartmouth community, both students and faculty became involved in the effort.

David Roberts, who had been with the Kennedy group, switched over to McCarthy in early January and helped organize the campaign out of the Lebanon headquarters. Professors Henry Ehrmann, Parke Burgess, and Alan Gaylord attended one of the early organizational meetings on the Dartmouth campus and were involved with the campaign from that point on. Robin Madrid, a faculty wife, organized faculty wives and women faculty members to work from the Lebanon headquarters. Lee Baldwin, David Kovenock, and Roger Davidson, all members of the Government Department, were also associated with the McCarthy effort. A group of senior government majors worked under Davidson and Kovenock during the winter term conducting and compiling a comprehensive poll of the New Hampshire voters. The poll studied the influence of religion, occupation, the Vietnam War, education, party affiliation, and past voting record on the expected vote of about 100 New Hampshire voters.

According to David Roberts, the contribution of the Dartmouth faculty to the McCarthy campaign was twofold. First, the faculty raised between $3000 and $4OOO for the campaign. Second, the faculty helped to organize and canvass the Upper Connecticut Valley.

Surprisingly enough, considering the nature of the McCarthy campaign in New Hampshire, the Dartmouth faculty probably contributed more to the campaign than the Dartmouth students. A campaign that would ultimately affect the history of the entire nation was being waged in Hanover, Lebanon, Enfield and Canaan. David Hoeh, a man who helped start the New Hampshire campaign, a man who helped set in motion the events which would bring Robert Kennedy into the Presidential campaign and leave President Johnson out of it, was barely known among Dartmouth students.

According to Dennis Donahue, a Dartmouth senior who spent a great deal of time working in the Lebanon headquarters, only about 75 Dartmouth students worked in the campaign. Most of them worked out of Lebanon. Donahue went to Hoeh during the first week of the winter term and said he wanted to work. His first task was to help find a headquarters in Hanover. Nothing could be found in Hanover and Donahue finally helped set up shop in a bare little room on the second floor of the Commerce Building in Lebanon. Donahue became one of the prime Lebanon coordinators, overseeing the canvassing and get-out-the-vote operations, although as he ob- served, 'lines of responsibility were vague and many people played an important role in the running of the headquarters."

Why did Dartmouth students respond so feebly to the McCarthy campaign when students from other colleges were pouring into New Hampshire by the hundreds to wage McCarthy's battle? Hoeh admits that he did not make any special effort to organize the Dartmouth campus. "I wanted it to be a statewide movement," he explained, "and so I was kind of bending the other way, trying to get the rest of the state involved. I don't think the students knew what was going on. The Dartmouth didn't pick up the McCarthy story until the national press had started giving it front-page coverage."

Some people tried to explain it by saying that final exams had conflicted with the end of the primary or that the trimester system kept the Dartmouth students too loaded down with work, but those weren't the real reasons. It seemed to come down to the mood of Dartmouth and its isolation from an urban environment.

"That's just the way Dartmouth is," said one student. "The guys took the New Hampshire primary for granted."

"The fact that we're out here in the woods has a lot to do with it," observed another student. "When you're in an urban atmosphere there is much more excitement. Politics goes on all the time. Up here it only becomes important once every two years."

Undoubtedly one of the reasons for the lack of enthusiasm was poor organization. There was no dynamic member of the student body or the faculty who took it upon himself to organize the campus. When McCarthy came to Dartmouth to speak, his appearance was not coordinated with any effort to recruit student volunteers.

But most of these answers beg the question. Why didn't Dartmouth organize spontaneously as many of the other New England schools seemed to do? Perhaps the primary was too close to home. Almost all of the candidates in the primary came to Dartmouth to speak. No one had to make any effort to leave the campus in order to get a glimpse of the campaign.

To a Dartmouth student, working for McCarthy meant going down to Lebanon. To a Mount Holyoke girl, working for McCarthy meant going to New Hampshire for the weekend. The romantic image was not the same.

A few Dartmouth students took time out from their spring vacations to work for McCarthy in Wisconsin. Larry Leshin, a freshman from Milwaukee, spent a good part of his vacation doing chores and driving volunteers in the week before the April 2 vote in Wisconsin.

Chris Hjermstad, a senior English major from Chicago, walked into the McCarthy press headquarters in Milwaukee two weeks before the primary and ended up taping all the Senator's speeches for the pressroom.

"I was talking to some resistance groups from MIT," said Hjermstad, "and I suggested that the best thing to do was to get a haircut and go out to Wisconsin. Then I thought, why not do it yourself since you're in a position to?"

Bob Keegan ended up working in Wisconsin on a whim. Bob is a Senior Fellow in English and last winter was awarded a Keasby Fellowship for two years of study at Oxford. He went home during the spring vacation to talk to his draft board about using the fellowship. They gave him an absolute no.

"I decided I was not going to serve in the army. It was the biggest question I had ever faced. Then one evening when I was thinking about all of this, I happened to be in a bar with a girl. We decided to go to Wisconsin and work for McCarthy." For three days Bob and the girl helped canvass the community of Wisconsin Rapids, 100 miles north of the state capital in Madison.

Bob's own small role in the April Wisconsin victory gave him a new outlook.

"Having seen this in Wisconsin, my faith was restored in the country. We had turned a corner and there was light at the end of the tunnel. At that point I reached a conclusion, which I haven't changed yet, that there is something worth staying for. There is a lot of human being in McCarthy: In the arrogance of challenging the President he still managed to keep his humility. I was considering not coming back to Dartmouth, but now I have a hope that ideals can win out. Something magic has happened already. here is a possibility that this great energy might continue."

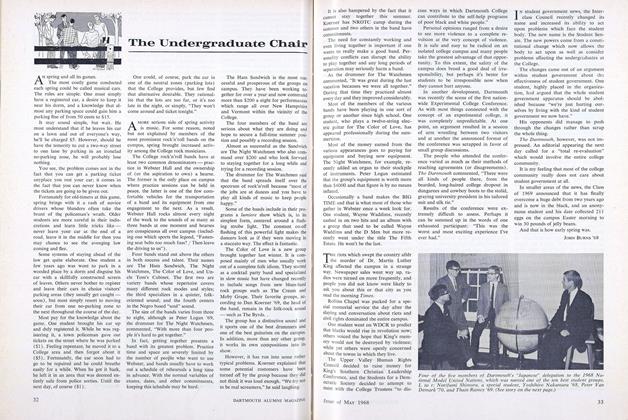

College volunteers at McCarthy headquarters in Wisconsin on primary night.

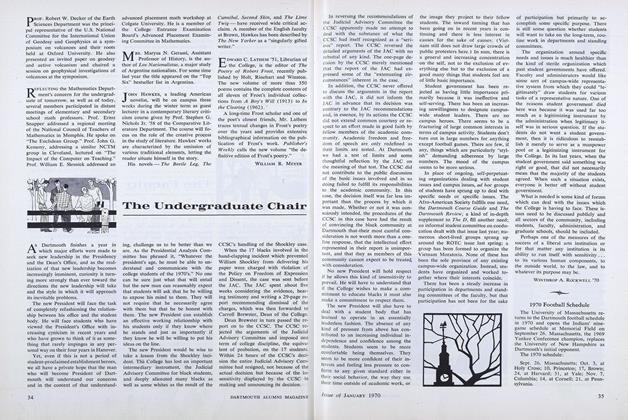

The focus of it all: Senator McCarthy inhappy mood as the primary vote came in.

Chris Hjermstad '68 of Chicago, who enlisted as a McCarthy worker in Wisconsinand got the job of taping speeches.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Alumni Relations

May 1968 -

Feature

FeatureThe Library Revolution

May 1968 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleOxford Revisited

May 1968 By JOHN G. GARRARD, -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

May 1968 By EARL H. COTTON, ROBERT G. THOMAS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

May 1968 By JILDO CAPPIO, ALBERT C. BONCUTTER

WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

NOVEMBER 1969 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JANUARY 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

APRIL 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70

Features

-

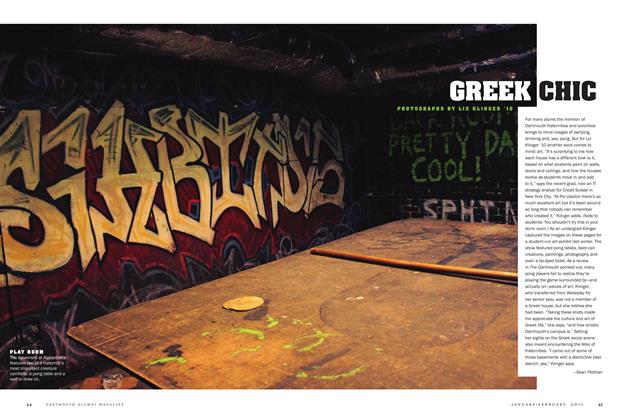

Feature

FeatureGreek Chick

Jan/Feb 2011 -

Feature

FeatureMr. Hopkins Builds a Library

April 1977 By CHARLES E. WIDMAyER -

Cover Story

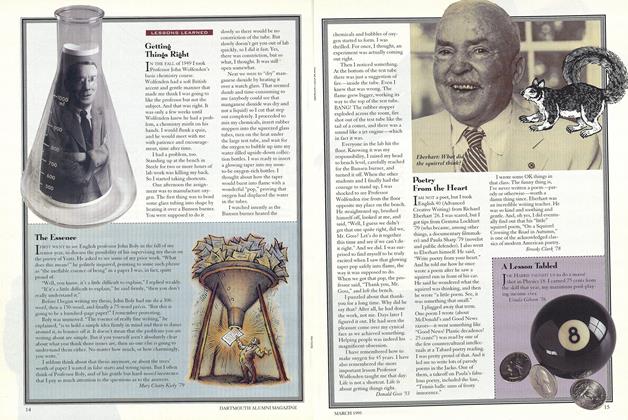

Cover StoryGetting Things Right

MARCH 1995 By Donald Goss '53 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2013 By JAMES KEGLEY -

Feature

FeatureThe "Greening" of the NFL

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

Feature"Veni, Vidi, victus sum."

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith