By Edson M. Chick.New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1967.154 pp. $4.50.

A major contribution to the hitherto slender body of Barlach criticism, this book by Professor Chick, Chairman of the Department of German, Dartmouth College, is the first extensive treatment published in English. It was no mean task to limn so complex a personality against the turbulent Germany of the 1920's and early '30's, surely the most exciting period in the evolution of the modern theater.

No German playwright of this century has so baffled his audience as Ernst Barlach (1870-1938); indeed, he was known chiefly as a sculptor. Few critics dealt with his literary output which includes seven plays and an autobiographical novel. A solitary, he paid homage to no tradition, period or political philosophy, but he has usually been linked with the Expressionist Theater of the 20's. Yet, as Professor Chick demonstrates, he cannot properly be called an Expressionist because, unlike them, he viewed man not as an abstraction but an entity caught between the eternal contradictions of heaven and earth.

Barlach's work reflects his own life and struggle for identity. His trip to Russia in 1906 stimulated his plastic expressiveness both as sculptor and writer and accounts for his subsequent preoccupation with the material, the flesh, and basic human appetites. Although he never abandoned the visible and real, his Russian experience intensified a fundamental dualism evidenced in his mysticism and asceticism. In Der tote Tag (1912) and Der arme Vetter (1918), the dominant theme is the ability or inability to see the world as it is. Man's primary contact with the world is through the "tyranny of his eyes," but, ironically, sight alienates him from the world. He cannot endure what he sees, including himself. It is not through seeing but mystical inner reflection and refraction which enables man to perceive himself, the world, and God.

Barlach sensed the profound crisis of Western art and civilization but found it difficult to translate this perception into words. The ambivalent, often grotesque, seemingly absurd, quality of his works stems in part from a fundamental scepticism about the power of words. The constant and paradoxical rebellion of the word against itself is, surprisingly, religious in origin. By using words, man demonstrates his worthlessness vis a vis God; words cannot describe God nor illustrate His greatness.

Barlach alternates between a sensual affirmation of life and Lebensangst, but this conflict is always tempered by a sardonic humor missing among the Expressionists. Like Dostoevsky, Barlach simultaneously sees the ugly, the comical, and the divine. Thus he portrays the nature and condition of modern man more poignantly than Bertold Brecht whose essentially two-dimensional characters manipulated by a rigid dramatic technique are but the mouthpieces of a dialectic world-view placing man on the side of either "good" or "evil," "progressive" or "reactionary." No less moral than Brecht, Barlach lets man, that confused, comical, and chaotic creature, speak for himself. Barlach's apparent obsession with materialism, his occasional blasphemy, and religious parody are cries of despair and longing for redemption. Professor Chick points out that herein lies the basically religious nature of Barlach's work giving it the quality of the medieval mystery plays. Indeed, much that is paradoxical and incongruous in him makes sense only in the light of this conclusion.

An Assistant Professor of German at Dartmouth College, Mr. Bruhn is currently writing on the conflict between tradition and the avant-garde at the turn of the century.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY AND STAFF

June 1968 -

Feature

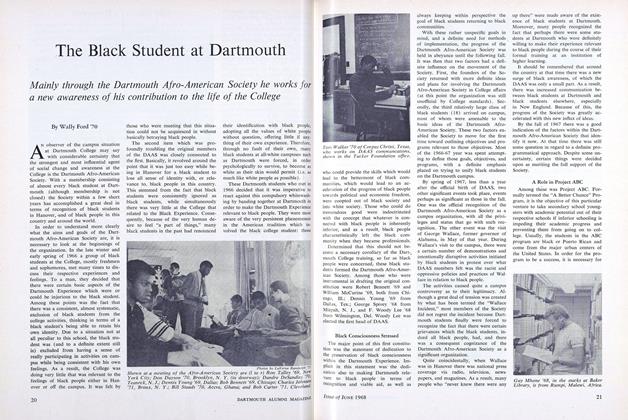

FeatureThe Black Student at Dartmouth

June 1968 By Wally Ford '70 -

Feature

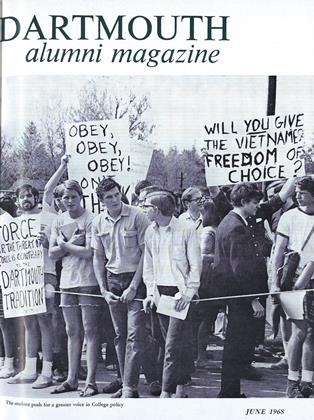

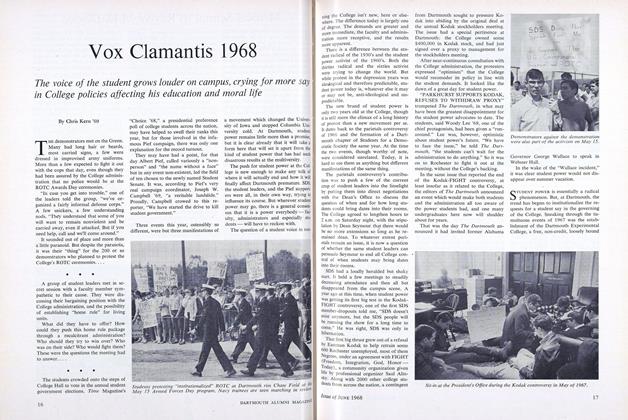

FeatureVox Clamantis 1968

June 1968 By Chris Kern '69 -

Feature

FeatureFour Steps Forward in Biology

June 1968 By PROF. RAYMOND W. BARRATT. -

Feature

FeatureShark Authority

June 1968 -

Feature

FeatureHeart Specialist

June 1968

Books

-

Books

BooksROBERT FULTON AND THE STEAMBOAT BOAT

February 1955 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksHANOVER, NEW HAMPSHIRE:

July 1961 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksJAPAN'S IMPERIAL CONSPIRACY: HOW EMPEROR HIROHITO LED JAPAN INTO WAR AGAINST THE WEST.

JANUARY 1972 By DONALD Bartlett'24 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

MARCH 1969 By J.H. -

Books

BooksMAS ALLA DEL HORIZONTE

July 1951 By R. Alberto Casas -

Books

BooksVERMONT IN THE MAKING

December 1939 By R. W. G. Vall