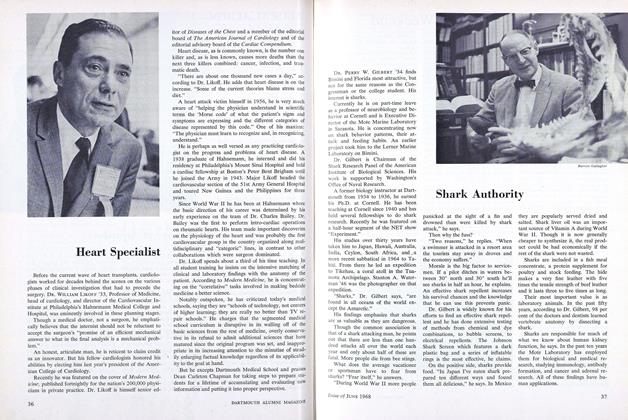

DR. PERRY W. GILBERT '34 finds Bimini and Florida most attractive, but not for the same reasons as the Congressman or the college student. His interest is sharks.

Currently he is on part-time leave as a professor of neurobiology and behavior at Cornell and is Executive Director of the Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota. He is concentrating now on shark behavior patterns, their attack and feeding habits. An earlier project took him to the Lerner Marine Laboratory on Bimini.

Dr. Gilbert is Chairman of the Shark Research Panel of the American Institute of Biological Sciences. His work is supported by Washington's Office of Naval Research.

A former biology instructor at Dartmouth from 1934 to 1936, he earned his Ph.D. at Cornell. He has been teaching at Cornell since 1940 and has held several fellowships to do shark research. Recently he was featured on a half-hour segment of the NET show "Experiment."

His studies over thirty years have taken him to Japan, Hawaii, Australia, India, Ceylon, South Africa, and. a more recent sabbatical in 1964 to Tahiti. From there he led an expedition to Tikehau, a coral atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago. Stanton A. Waterman '46 was the photographer on that expedition.

"Sharks," Dr. Gilbert says, "are found in all oceans of the world except the Antarctic."

His findings emphasize that sharks are as valuable as they are dangerous.

Though the common association is that of a shark attacking man, he points out that there are less than one hundred attacks all over the world each year and only about half of these are fatal. More people die from bee stings.

What does the average vacationer or sportsman have to fear from sharks? "Fear itself," he answers.

"During World War II more people panicked at the sight of a fin and drowned than were killed by shark attack," he says.

Then why the fuss?

"Two reasons," he replies. "When a swimmer is attacked in a resort area the tourists stay away in droves and the economy suffers."

Morale is the big factor to servicemen. If a pilot ditches in waters between 30° north and 30° south he'll see sharks in half an hour, he explains. An effective shark repellent increases his survival chances and the knowledge that he can use this prevents panic.

Dr. Gilbert is widely known for his efforts to find an effective shark repellent and he has done extensive testing of methods from chemical and dye combinations, to bubble screens, to electrical repellents. The Johnson Shark Screen which features a dark plastic bag and a series of inflatable rings is the most effective, he claims.

On the positive side, sharks provide food. "In Japan I've eaten shark prepared ten different ways and found them all delicious," he says. In Mexico they are popularly served dried and salted. Shark liver oil was an important source of Vitamin A during World War II. Though it is now generally cheaper to synthesize it, the real product could be had economically if the rest of the shark were not wasted.

Sharks are included in a fish meal concentrate, a protein supplement for poultry and stock feeding. The hide makes a very fine leather with five times the tensile strength of beef leather and it lasts three to five times as long.

Their most important value is as laboratory animals. In the past fifty years, according to Dr. Gilbert, 98 per cent of the doctors and dentists learned vertebrate anatomy by dissecting a shark.

Sharks are responsible for much of what we know about human kidney function, he says. In the past ten years the Mote Laboratory has employed them for biological and medical research, studying immunology, antibody formation, and cancer and adrenal research. All of these findings have human applications.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY AND STAFF

June 1968 -

Feature

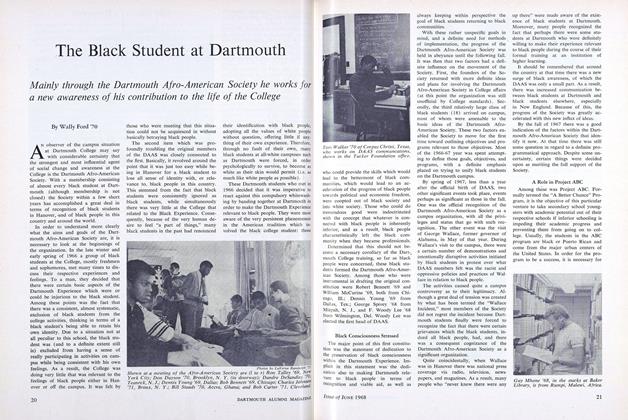

FeatureThe Black Student at Dartmouth

June 1968 By Wally Ford '70 -

Feature

FeatureVox Clamantis 1968

June 1968 By Chris Kern '69 -

Feature

FeatureFour Steps Forward in Biology

June 1968 By PROF. RAYMOND W. BARRATT. -

Feature

FeatureHeart Specialist

June 1968 -

Feature

FeatureWinner at Aqueduct

June 1968

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1964

JULY 1964 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Starscape That Is Just Amazing"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHASKELL THE RASCAL

May/June 2013 -

Feature

FeatureRichard Hovey: The Incomplete Arthurian

DECEMBER • 1986 By Daniel P. Nastali -

Feature

FeatureThe naivete of nuclear rivalry

MARCH 1982 By George Kennan -

Feature

FeatureCan Chinese Civilization Survive Communism?

November 1959 By WING-TSIT CHAN