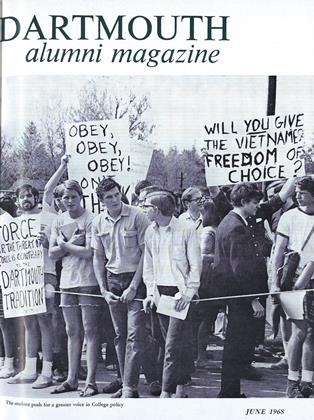

The voice of the student grows louder on campus, crying for more sayin College policies affecting his education and moral life

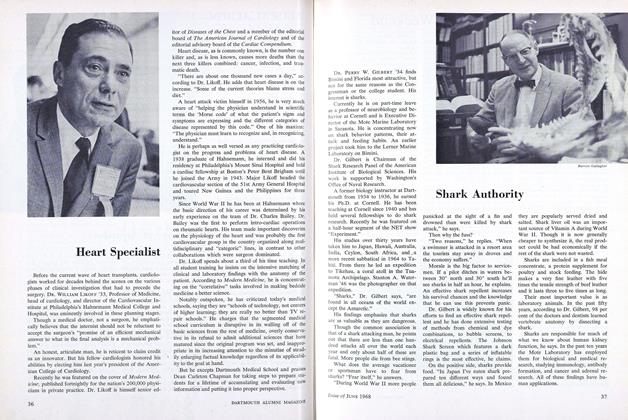

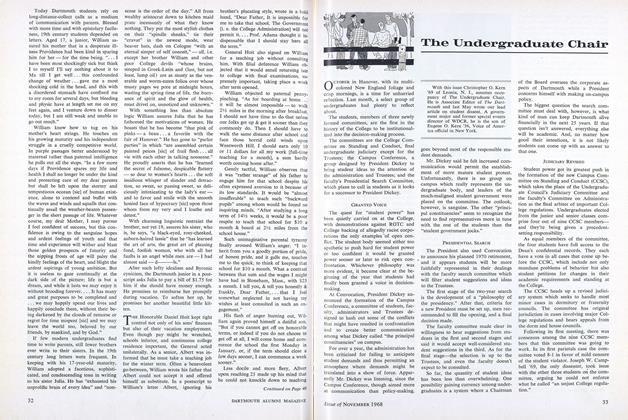

THE demonstrators met on the Green. Many had long hair or beards, most carried signs, a few were dressed in improvised army uniforms. More than a few expected to fight it out with the cops that day, even though they had been assured by the College administration that no police would be at the ROTC Awards Day ceremonies.

"In case you get into trouble," one of the leaders told the group, "we've organized a fairly informal defense corps." A few snickers, a few understanding nods. "They understand that some of you will want to remain nonviolent and be carried away, even if attacked. But if you need help, call and we'll come around."

It sounded out of place and more than a little paranoid. But despite the paranoia, it was their "thing" for the 200 or so demonstrators who planned to protest the College's ROTC ceremonies....

A group of student leaders met in secret session with a faculty member sympathetic to their cause. They were discussing their bargaining position with the College administration, and the possibility of establishing "home rule" for living units.

What did they have to offer? How could they push this home rule package through a recalcitrant administration? Who should they try to win over? Who was on their side? Who would fight them? These were the questions the meeting had to answer....

The students crowded onto the steps of College Hall to vote in the annual student government elections. Time Magazine's "Choice '68," a presidential preference poll of college students across the nation, may have helped to swell their ranks this year, but for those involved in the infamous Pief campaign, there was only one explanation for the record turnout.

They may have had a point, for that day Albert Pief, called variously a "nonperson" and "the name without a face" but in any event non-existent, led the field of ten chosen to the newly named Student Senate. It was, according to Pief's very real campaign coordinator, Joseph W. Campbell '69, "a veritable landslide." Proudly, Campbell crowed to this reporter, "We have started the drive to kill student government."

Three events this year, ostensibly so different, were but three manifestations of a movement which changed the University of lowa and stopped Columbia University cold. At Dartmouth, student power remains little more than a promise, but it is clear already that it will take a form here that will set it apart from the kind of student power that has had such disastrous results at the multiversity.

The push for student power at the College is new enough to make any talk of where it will actually end and how it will finally affect Dartmouth premature. SDS, the student leaders, and the Pief supporters were all, in their own way, trying to power may go, there is a general consensus that it is a power everybody—faculty, administrators and especially students - will have to reckon with.

The question of a student voice in running the College isn't new, here or elsewhere. The difference today is largely one of degree. The demands are greater and more immediate, the faculty and administration more receptive, and the results more apparent.

There is a difference between the student radical of the 1930's and the student power activist of the 1960'5. Both the thirties radical and the sixties activist were trying to change the world. But while protest in the depression years was ideological and therefore predictable, student power today is, whatever else it may or may not be, anti-ideological and unpredictable.

The new brand of student power is only two years old at the College, though it is still more the climax of a long history of protest than a new movement per se. It dates back to the parietals controversy of 1966 and the formation of a Dartmouth chapter of Students for a Democratic Society the same year. At the time the two events, though worthy of note, were considered unrelated. Today, it is hard to see them as anything but different manifestations of the same thing.

The parietals controversy's contribution was to push a few of the current crop of student leaders into the limelight by putting them into direct negotiations with the Dean's Office to discuss the question of when and for how long students could bring dates into their rooms. The College agreed to lengthen hours to 2 a.m. on Saturday night, with the stipulation by Dean Seymour that there would be no more extensions so long as he remained dean. To whatever extent parietals remain an issue, it is now a question of whether the same student leaders can persuade Seymour to end all College control of when students may bring dates into their rooms.

SDS had a loudly heralded but shaky start. It held a few meetings to steadily decreasing attendance and then all but disappeared from the campus scene. A year ago at this time, when student power was getting its first big test in the Kodak-FIGHT controversy, one of the first SDS member-dropouts told me, "SDS doesn't exist anymore, but the SDS people will be running the show for a long time to come." He was right, SDS was only in hibernation.

That first big thrust grew out of a refusal by Eastman Kodak to help retrain some 600 Rochester unemployed, most of them Negroes, under an agreement with FIGHT (Freedom, Integration, God, Honor - Today), a community organization given life by professional organizer Saul Alinsky. Along with 2000 other college stu- dents from across the nation, a contingent from Dartmouth sought to pressure Kodak into abiding by the original deal at the annual Kodak stockholders meeting. The issue had a special pertinence at Dartmouth: the College owned some $400,000 in Kodak stock, and had just signed over a proxy to management for the stockholders meeting.

After near-continuous consultation with the College administration, the protesters expressed "optimism" that the College would reconsider its policy in line with the student demands. It looked like the dawn of a great day for student power.

"PARKHURST SUPPORTS KODAK, REFUSES TO WITHDRAW PROXY" trumpeted The Dartmouth, in what may have been the greatest disappointment for the student power advocates to date. The students, said Woody Lee '68, one of the chief protagonists, had been given a "run-around." Lee was, however, optimistic about student power's future. "We have to face the issue," he told The Dartmouth, "the students can't wait for the administration to do anything." So it was on to Rochester to fight it out at the meeting, without the College's backing.

In the same issue that reported the end of the Kodak-FIGHT controversy, at least insofar as it related to the College, the editors of The Dartmouth announced an event which would make both students and the administration all too aware of the power students had, and one many undergraduates here now will shudder about for years.

That was the day The Dartmouth announced it had invited former Alabama Governor George Wallace to speak in Webster Hall.

In the wake of the "Wallace incident," it was clear student power would not disappear over summer vacation.

STUDENT POWER is essentially a radical phenomenon. But, at Dartmouth, the trend has begun to institutionalize the requests for a student say in the governing of the College. Sneaking through the tumultuous events of 1967 was the establishment of the Dartmouth Experimental College, a free, non-credit, loosely bound collection of courses designed for enrichment of students, faculty, and area residents.

The man rwho pushed it through, Robert B. Reich '68, is a different type of student-power activist. Instead of "confrontation" with the administration, Reich has sought to bargain with the College. Reich is a politician by nature and a student-power activist by accident and an excess of energy. His DEC is only one of the things Reich will leave behind at Commencement, but it has become a part of the College, and this is significant.

When it held its first classes in January 1967, the DEC was looked on tolerantly but paternalistically by the College administration. Today, Dartmouth's publicity trumpets the Experimental College as an outstanding example of student initiative.

Similarly, the move for "home rule" in College living units, the right of dorms and houses to make and enforce their own social regulations, met stiff resistance from the faculty Committee on Administration. But a few students pressed the issue, and politicked with real fervor, and now Assistant Dean James Cowper-thwaite's new judiciary proposal, which appears well on the way to passage, will give those students a strong measure of the home rule they sought.

Significantly, the "Cowper-thwaite proposal" is something less than the home rule activists had hoped for. It does not give full power over parietal regulations, one of the cornerstones of "home rule." But, as Cowper-thwaite concedes, "it's more than you've got now."

Meanwhile, the student body has been moving away from its formal student government, as the ad hoc groups (some of which become in time permanent parts of the undergraduate scene) proliferate. The feeling has become overwhelming that student government has turned into student bureaucracy, an "alphabet soup" of UGC's and ICC's and IFC's and IDC's (from left to right, the Undergraduate Council, the Interclass Council, the In-terfraternity Council, and the Interdormitory Council). A vote for student government, editorialized The Dartmouth in endorsing noncandidate Albert Pief, was "A Vote for Nothing."

Pief was the concoction of Joseph W. Campbell '69 and Fred J. Klein '69. Never enamored of student government, the duo thought they could prove its valuelessness by running a nonperson for the Inter-class Council. (Shortly before the election, the ICC changed its name to "Student Senate," possibly as a reaction to "alphabet soup." The majority of undergraduates, however, saw it more a proof that student government was a "Mickey Mouse" affair.)

Campbell and Klein issued press releases from Pief "election central" in Streeter Hall to the sympathetic directorates of The Dartmouth and WDCR. They plastered Pief posters everywhere, spread the gospel by word of mouth and saturated the air waves with advertisements for Pief on WDCR. By election day, Pief was all too well known by everyone at the College.

"Everywhere I go," one Thayer diner complained to Campbell, "I see 'Pief.' Who the hell is Pief?"

"A great leader," Campbell intoned piously, "Vote for him."

They did. They voted for Pief in droves. But what is important is that the barely half-serious Pief candidacy developed after his election into a full-fledged movement to abolish student government.

While Campbell and Donald C. Pogue '69, a disgruntled former student government leader, plotted strategy, the newly elected student government worried. Campbell and company were pushing for a campus-wide referendum. At least two members of the old Palaeopitus favored abolition. The movement was gaining momentum.

In an open meeting on student government, the new leaders managed to push through a compromise which called for review of student government in the fall. But it appears that student government at Dartmouth will not be the instrument of student power.

WHAT the instrument will be remains an open question. SDS has made a bid, after its year of dormancy. In early May, SDS spearheaded a movement to "de-institutionalize" ROTC from the College. It reasoned (1) that the ROTC contract was coercive, and should not be enforced even tacitly by Dartmouth, (2) that ROTC courses were not in line with the educational objectives of the College and should be removed from the curriculum, and (3) that the ROTC instructors, paid by the military, did not belong on the faculty.

The aims of SDS drew fairly wide campus backing. "We are not asking for the College to kick ROTC off campus,' said the editors of The Dartmouth. "Such a move would deprive a sizable number of students of the right to take advantage of the benefits ROTC offers.... We do feel it should be strictly an extracurricular activity."

The means of SDS were less favorably received. Using the College's annual Armed Forces Day ceremonies as a target, SDS promised "direct public action' if its demands were not met.

After Columbia, the vague phrase "direct public action" was calculated to upset everyone. It did.

heedless to say, few outside SDS were looking forward to a Columbia-style incident at Dartmouth. "The SDS demands are not reasonable and should not be accepted by the College," editorialized America's Oldest. "How can a group which for the past two years has clamored for the right to demonstrate and championed the cause of academic freedom, but then turns around and threatens to deny another group its right to demonstrate, possibly hope to gain the respect of the community?"

The editorial board of The Dartmouth was angry. The administrators in Parkhurst were frankly worried. Strategies were hashed out, all reaction complicated by the vague nature of the SDS threat and the lack of sure knowledge of what the group would actually do on May 15.

Calling in police, as had been done last year after similar but milder threats, was ruled out. That was seen as a direct invitation to "confrontation." Calling off the Armed Forces Day ceremonies was ruled out. Capitulation now would mean capitulation later. Nevertheless, it was clear SDS had raised a legitimate issue, whatever its threats of illegitimate action. Did ROTC deserve to be "institutionalized" by the College?

This was not the first time the issue had been raised. For years, members of the faculty, and not necessarily the radical members, had questioned the amount of backing given to ROTC by Dartmouth. On the other hand, the real issue threatened to be obscured by "direct public action."

A forum was held in the Top of the Hop, with speakers pro and con ROTC. The ROTC instructors had their say, so did Gil Tanis, Executive Officer of the College and Dartmouth's "military coordinator." So did SDS.'

For a week before Armed Forces Day, there was only one issue on campus. Arid there was only one question, asked everywhere: "What is SDS going to do?"

On Friday, May 10, SDS made its decision. Saturday, they released it to WDCR. SDS would sponsor a "peaceful, non-disruptive" demonstration at the ROTC ceremonies.

There was an air of tension on Chase Field May 15, as the protesters, 200 strong, filed onto the field and surrounded the ROTC ceremonies. But, true to their promise, the protest was peaceful.

SDS didn't get what it wanted, at least not right away. But the Executive Committee of the Faculty has asked its Committee on Organization and Policy "to report ... on the compatibility of the ROTO programs with the educational objectives of the College."

SDS did get the community talking about ROTC, and this was the group's real objective. It seems safe to say there would have been no real dialogue about ROTC without the threat, probably never meant to be carried out, of "direct public action." The students, or at least one group of them, had exercised a very clear and quite potent brand of "student power."

AN institution like Dartmouth doesn't just change, it evolves. It is impossible to understand a movement like student power without looking back on its development. It is difficult to guess where it will go.

Three trends seem clear, however. First, student power will continue to be exercised both within and without the College power structure.

Second, student power will continue to grow outside the ranks of formal student government. Ad hoc or special interest groups, with clear and limited objectives and no dead weight, are far more able to exercise student power than any kind of student government bureaucracy.

Third, student power is not absolute. Limited objectives may be realized intact, the more far-reaching goals will be watered down, if they go into effect at all. Student power will not eclipse administration power, or faculty power, or alumni power, or the power of outside public opinion. Rather the goals and strengths of each kind of power must be evaluated for every issue.

When the Class of 1968 graduates June 16, it will leave a Dartmouth clearly different from the College it entered. But every class does this, for no institution so complex as Dartmouth College can avoid change. Student power is more important now than it was when the '68s came to Hanover; in a very real way it did not exist four years ago. And student power in Dartmouth's third century will undoubtedly be more important than it is now.

But, however trite, power must be measured in terms of what it does as well as in terms of how much of it there is. And it is still too early to make that sort of judgment.

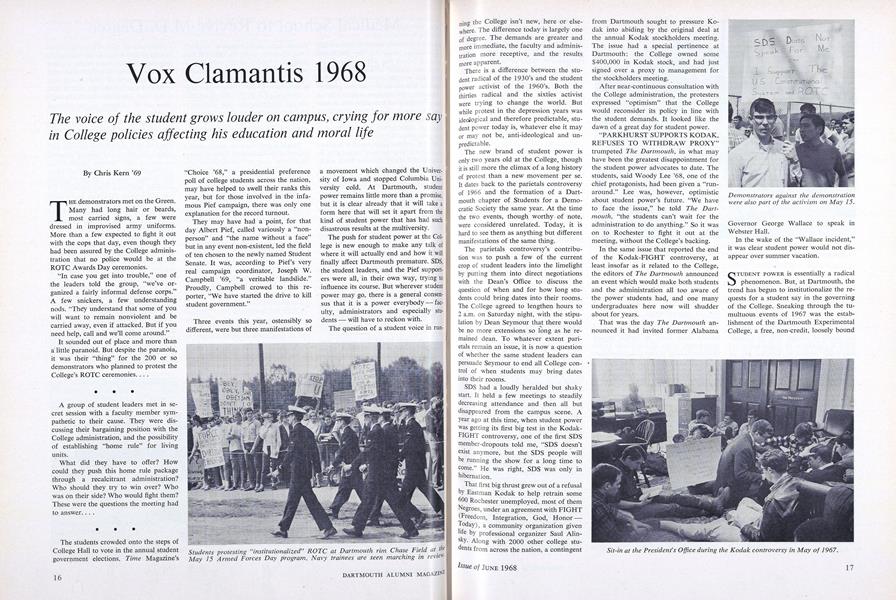

Students protesting "institutionalized" ROTC at Dartmouth rim Chase Field at theMay 15 Armed Forces Day program. Navy trainees are seen marching in review.

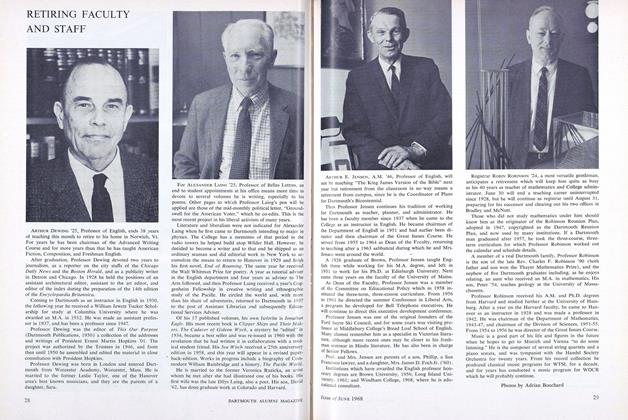

Demonstrators against the demonstrationwere also part of the activism on May 15.

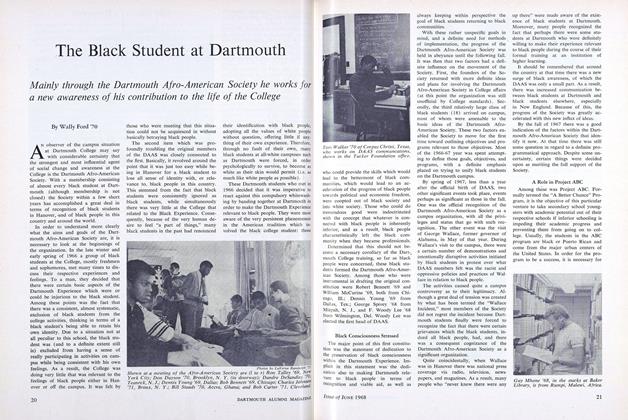

Sit-in at the President's Office during the Kodak controversy in May of 1967.

"Peace" is the one word around which student demonstrators can rally with unanimity, and here it heads the long procession to Chase Field on Armed Forces Day.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Chris Kern '69

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JANUARY 1970 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

October 1974 -

Article

ArticleGRANTED VOICE

November 1968 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Article

ArticleJUDICIARY REVISED

November 1968 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69

Features

-

Feature

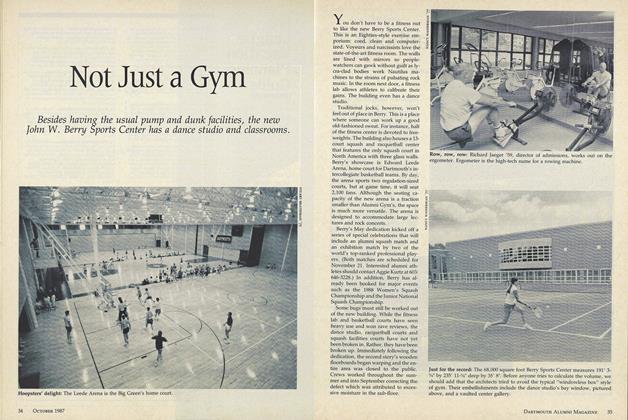

FeatureNot Just a Gym

OCTOBER • 1987 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Woodsy Time Line

NOVEMBER 1989 -

Feature

FeatureMaking Music

November 1978 By Dana Grossman -

Cover Story

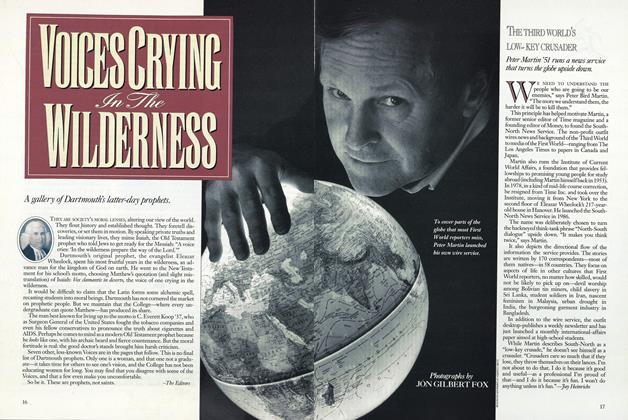

Cover StoryTHE THIRD WORLD'S LOW-KEY CRUSADER

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureMore than a beast, Less than an angel

October 1974 By PETER A. BIEN -

Feature

FeatureThayer School's Centennial

OCTOBER 1971 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28