Willy-nilly, the U.S. educational system is spawning a generation of semi-literates. Newsweek December 1975

Anyone who reads student writing today knows that students can't write. Yale Alumni Magazine January 1976

College freshmen now read at what used tobe considered the junior-high-school level;they write in fragments and cannot thinkat all. Harper's September 1976

WITH the national hue and cry against illiteracy ringing in my ears, I went on assignment in search of the thing at Dartmouth. I spoke with several people at the English Department, checked in History, and telephoned Sociology and the Reading and Study Skills Center. I enquired in Mathematics and Business, at the Engineering School, the Radiophysics Laboratory, the Admissions Office, and the Medical School. Not everywhere that might profitably have been visited, I admit - but a fair sampling and all my deadline allowed.

"There has been no decline in literacy among Dartmouth students in the 11 years I've been here," said Dr. David J. Bradley '38, author and senior lecturer in Effective Writing & Speaking at Tuck. "I've been teaching for 15 years - here and at Harvard - and I don't think there's any new crisis in writing," declared Chairman Charles Wood of History.

Chauncey Loomis, chairman of the English Department, assured me that there has been no essential change in the writing abilities of Dartmouth students in recent years; and Professor James Heffernan, who directs English 5 (Dartmouth's freshman composition course), felt he could fairly state that the general level of literacy among entering students at Dartmouth actually rose this year (though only very slightly), an opinion he bases on a decrease in the number who needed English 2, the course required of those not ready for 5. Karen Pelz, who directs the College's Reading and Study Skills Center and teaches English 2 as well, said she really does not think there has been a decline in literacy at Dartmouth.

The head of the Mathematics Department felt he had too little experience with student writing to comment, and Professor of Physiology Allan Munck said, "The form of medical school examinations has changed in recent years so drastically [away from essay and toward multiple choice] that we are not able to evaluate whether there has been a decline in literacy here." But Professor James Davis, a former journalist now chairman of the Sociology Department, stated categorically that the average Dartmouth student's writing ability has not changed for the better or for the worse in the eight or so years of his experience with it.

At Thayer, Engineering Dean Carl Long shook his head: "No decline that I'm aware of." Michael Hanitchak '73 in the Admissions Office reported that College Board verbal scores have been steady at Dartmouth for the last three years, the median varying an insignificant ten points or so. "We have seen no significant drop in the verbal SAT scores of our first-year students," he announced. Even Professor of English Peter Bien, founder of the College's new writing clinic (the Resource Center for Composition), said there has been no decline.

I had not expected such an answer, and I certainly had not expected it so consistently. Nor was I prepared for what, in every single case, followed it: a careful analysis of the very great difficulties Dartmouth students have with writing.

"VERY few of our freshmen," Peter Bien feels, "can write their own language without serious errors (not to mention confused thought), and all too many seniors graduate writing embarrassingly poorly. Note that I speak not only of our so-called disadvantaged students, but of all undergraduates." He refers to "verbal cripples" and asserts that not one in ten Dartmouth students will know, for example, the difference in meaning between these two sentences:

The army which was best took the lead.The army, which was best, took the lead.

Professor Heffernan says that very few Dartmouth freshmen "have had any experience writing in high school, or any explicit exposure to the rules of grammar. Most, therefore, are unable to write a coherent paragraph." Estonian-born Professor Thomas Laaspere of Radiophysics, who publishes in English (his third language), feels, "We should turn out graduates from Dartmouth College who can write better. Most barely meet minimum requirements, and some don't do even that."

"Their writing has no character at all," was Professor Wood's complaint about undergraduate prose. Three out of four of all the graduate laboratory assistants Allan Munck has directed have had "almost chronic writing problems." Dean Long explained with eloquent relief how he hopes that Peter Bien's Resource Center will rescue his faculty from having to choose between failing a student unable to write and writing the thesis themselves.

The distressing explanation behind the consensus that there has been no decline in literacy at Dartmouth is - It has alwaysbeen this bad. (For at least 15 years, anyway.)

Carl Long said it: "The problem has existed with Americans always. Things aren't worse; we're just more concerned now." Jim Heffernan and David Bradley dismissed my fevered questions about a literacy crisis at Dartmouth. "It's an autumnal rite, this handwringing about how Johnny can't write," said the one, and the other concurred: "The 'crisis' isn't a crisis at all. These things have been said repeatedly before. It is a cyclical disturbance."

Are the students themselves concerned? The undergraduates may be a little more concerned than in the past - but apparently not much. English major Andrea Jordan '77 reports some small awareness among students of the idea of a national literacy crisis, but says it is not really a topic of discussion. "Most students don't think they can't write," she says, "but English majors think there is a problem among Dartmouth College students, a problem with basic grammar." Jim Heffernan agrees with her that Dartmouth freshman are not aware that they cannot write properly. Many a student, he reports, is shocked to see the grade on the first composition paper and is apt to appear shortly on his doorstep, bleating indignantly, "But no one ever corrected my grammar before!" Jim Davis says he refers students to the Resource Center for Composition, but they don't go.

Chauncey Loomis, on the other hand, is beginning to feel pressure from students. "They've been told they can't write by television, magazines, newspapers - not just some old archaic pedant of an English teacher - and now they're worried," he says. Of those exempted from English 5 this year, a good 15 made a fuss about not being allowed to take the course. "Last year," says Loomis, "students streamed in and stood in line" for the department's one elective expository writing course; and when the course was withdrawn this year for lack of staff, one angry student expostulated, "But you are obliged to give such a course!"

There is no question about concern among graduate students, according to Professor of Physiology Charles Wira, who as a graduate student at Dartmouth found himself faced with a doctoral thesis and a writing problem of mammoth proportions, for which he sought help unavailingly throughout the College. Finally he located an undergraduate English major willing to tutor him. "Our graduate students would take a course in writing were it offered," he says feelingly. "They would make time for it, with gratitude. It would save untold agonies of time trying to write in the dark."

Most of those I saw, including Wira, agreed that trouble with the basic mechanics of writing, though a frequent problem, usually is easily corrected. "It's easy enough," says Charles Wood, "to get looseness tightened so students are writing functionally. A student finds out after the first paper that he or she has to write English in History too and begins to shape up." "In many cases," Peter Bien reports, "you hit the student over the head once, and he or she is fine." Jim Heffernan, though amazed at the sloppiness of entering students (they can write grammatical sentences, he says, but they don't), admits "they learn rapidly."

PETER Bien's brain child, the Resource Center for Composition, was designed specifically to deal with these mechanical difficulties - "problems of punctuation, spelling, sentences vs. nonsentences, restrictive vs. non-restrictive clauses, irregular plurals, proof-reading, dangling constructions, misused words, distorted idioms, mixed metaphors, pronouns without antecedents, faulty agreement." Using time and money awarded him two years ago as the first holder of the Ted and Helen Geisel Third Century Professorship in the Humanities, Peter arranged in Sanborn House a room for writers in trouble and stocked it with trained undergraduate tutors, a choice collection of grammar handbooks, composition texts, and dictionaries, and a file cabinet full of homemade drills and worksheets patterned after those used by Mina Shaughnessy (who singlehandedly shaped up the writing programs of the city colleges of New York).

Students come in on their own, or they are referred by instructors. When they arrive, Nina Dorrance '77, the brusque, hearty head tutor, greets them with a slap on the back in her voice: "What dp you mean you can't write? Of course you can write. You wouldn't be at Dartmouth if you couldn't write!" (Lack of confidence, Nina feels, is one of the greatest difficulties under which a troubled writer labors.) Nonetheless, the student is at Dartmouth, and someone - student or professor - feels that he or she can't write. So Nina assigns a tutor, who is also a compeer, and the two work together on the problem for as long as it takes.

The five tutors are paid for their work (at the usual academic rates), and Peter Bien directs them from the wings. In the spring of 1976, 44 students - 35 of whom came in of their own accord - used the composition center for a total of 239 tutorial sessions, most of which involved drilling on punctuation, especially the comma and the semicolon. Peter hopes the center will go a long way toward freeing the teachers of English 5 from the need to teach mechanics, since, as he points out, "A university-level course in composition ought to concentrate on organization and style."

It is in these two areas, all are agreed, that the greatest writing problems at Dartmouth exist. Dartmouth's difficulties are the same as those of which Brown University complains: "The alarming thing about students' ability to write," says its Professor Van Nostrand, "is not that their grammar is weak or that they don't know how to construct a decent sentence. It is, rather, that they cannot string sentences together to form a coherent paragraph that completes a process of thought."

For many of the students writing at Dartmouth, says Jim Heffernan, "things like coherence, organization, emphasis, art of repetition, and similar rhetorical skills simply never come into the picture." "They lack a feeling," observes Allan Munck, "for the logical structure of a paragraph and a sentence, a simple straightforward sentence that says what somebody means," and he compares reading the work of many of his students to trying to talk through a bad telephone connection: the lack of clarity quickly becomes terribly irritating, terribly frustrating.

"We're disappointed around here that there is so little that is well-written on the application essays we get, so little that's interesting to read," says Mike Hanitchak in Admissions; Dr. Bradley speaks of "confused expression" and calls for more clarity and forcefulness; and both Charles Wood and Jim Heffernan lament the loose, sloppy characteristics of writing which is modeled, they feel, too much on casual, rambling, unrevised speech.

THE causes? Well, yes, television is a contributor; but it has been the bete noire for so long that as such it has earned the contempt bred of familiarity. It plays its part, doubtless keeping students of all ages away from the written word, and so do advertising (with its sentence fragments and clever misspellings), newspapers (even the New York Times omits apostrophes), and computers (most of which do not use apostrophes or capital letters). But all of those to whom I spoke were concerned with deeper - or at least other - causes.

A couple of them speculated largely, with a philosophical flourish. Said Charles Wood, "The problem is that any genuinely literary language carries an awful lot of value judgments, and in any pluralistic society there will not be any agreement on those values. The tension between those values and the pluralism is what we are wrestling with." Jim Heffernan pronounced sweepingly upon another cause: "What's hampering the dissemination of literacy in the College (and in society as a whole) is the tendency of the educational process to create specialists."

But most stayed much closer to home, if not, in fact, in it. Homes and schools were cited again and again as neglecting to provide young people with any experience at writing well. Karen Pelz summed it up in one word: underexposure. "Just the other day," she recalled, "a student told me that she had never in her life written anything but a first draft. Whatever she wrote simply came off the top of her head and went directly onto the paper, and that was that." "High school students are getting no experience writing papers that are carefully marked for writing, and so the ability to write atrophies" is Chauncey Loomis' feeling. "Too few writing exercises in high school," says Peter Bien, "and improper correction of what there is. When there is correction, there is no rewriting or conference."

Some felt that this failure on the part of the schools was attributable to writing incompetence in the teachers themselves. And Professor Long picked up from his desk a frame containing a photograph of his daughter and a copy of a poem she wrote at the age of six. He showed it to me and said wistfully, "Her writing is not being corrected in high school. They don't care, I guess."

But the overwhelming response was that school teachers lack the time to teach students to write well. "And," said David Bradley, pausing significantly, "you know that a Princeton study eight years ago found that the only thing - the only thing - that makes a measurable difference to the teaching of composition is the size of the class. It's easy to teach composition to a class of 12." (Time, of course, is money. Heaven knows the problem these days isn't a dearth of English teachers.)

MANY also felt that lack of experience in writing had been aggravated by the sentimental attitude toward writing taken by many educators in the 19605. Thomas Laaspere's lip curled involuntarily as he spoke of the notion that "originality, creativity, ideas are all that matter in writing, and the way in which something is expressed is not important." Both he and Jim Heffernan derided the assumption, of which they accused the Sixties, that the ability to write is as instinctive as the ability to breathe, or to talk, and requires no greater conscious effort or practice. "Creativity and self-expression are not possible in writing apart from the discipline of literary models," said a tightlipped Peter Bien. Andrea Jordan, herself a product of the Sixties, agreed, and she reported with earnest satisfaction that a questionnaire recently circulated among English majors indicates a wide-spread desire for more structure, more rigor, more writing from models in Dartmouth's English courses.

Perhaps hard work is coming back into fashion. "There is an unfortunate emphasis these days on making courses 'exciting,' " complains Laaspere. "We are afraid to make work hard. I have published often in English, and editors commend my writing. I write well not because it comes easy, but because I pay careful attention." Students seem not to know, says Jim Heffernan, that good writing demands rewriting: the investment of that much effort in a composition is a shocking idea to many of them.

The buck was not being passed, however. Without an exception, those to whom I spoke excoriated the College itself for the same omissions, the same underexposure. They laid a good measure of the blame for the writing problems of the Dartmouth student at the door of their own august membership. "We faculty don't demand that students write much if anything beyond the freshman year," they said, "and when they do write for us, many of us do not demand that they write well."

All said it, but David Bradley said it most forcefully. "Albert Kitzhaber," he reminded me, "made in 1958 a study of freshman writing at Dartmouth [published as Themes, Theories, and Therapy, McGraw-Hill, 1963], Kitzhaber found a very important phenomenon operating here, and he drew from it a very important conclusion. He found that our students wrote much better at the end of the freshman year than they did at the end of the senior year. And he concluded that there is not a damned thing to be done about that unless the faculty as a whole has a standard to which it holds students.

"It's no use badgering the poor old English Department. As long as the faculty are unwilling to get mad at rambling, discursive, ill-organized, imprecise - even worse, ungrammatic - writing and insist on a good performance, nothing will happen." Faculty members do not all need to become composition experts, according to Bradley (and Peter Bien agrees): "They only have to learn to write in the margin, 'I refuse to read this baloney any further.' We need more of the great apoplectic teachers who refuse to stand for careless writing, curmudgeons with too much selfrespect to read hogwash." He paused and then summed it up more formally: "If the faculty react, the students will react."

The others echoed him. "Two months of English 5 are not enough; writing must be sustained and developed elsewhere in the College." "A student rescued by English 5 sinks back into the murk of illiteracy when subsequent College courses do not require him or her to write." "Perhaps 25 per cent of the faculty are seriously concerned about writing. Fifty per cent are so-so about it,-and another 25 per cent are not concerned at all."

Already the graduate faculties are reacting. Law schools are writing to Chauncey Loomis warning him of their demands for good writing. Dartmouth's engineering school has instituted a "design" course which requires several written papers and oral presentations, each of which is graded by three separate faculty members. (For some engineering students, says Dean Long, it's the only course after freshman year that calls for using words as well as numbers.) Tuck School hired David Bradley - a man who gave up the surgeon's knife after the Bikini tests to wield the pen he considered mightier - to lecture on effective writing. And if the Physiology Department is any indicator, the Medical School is beginning to foam at the mouth.

THAT'S my report on why Johnny (and, one must assume, Jill) at Dartmouth can't write. What remains is to pass on to Dartmouth alumni and alumnae the messages to them that I solicited from the people I interviewed.:

Tell your children that it is important that they learn how to write and speak the English language.

If we could find more candidates with 800 verbal scores, it would be nice. Seven and eight hundred math scores are a dime a dozen, but only one out of 10,000 verbals is in the 800-range. We see only one or two a year.

You learn to write by writing.

If you care about writing, you must communicate the fact to your children. Read what your children write, analyze and correct it to the extent that you can. The schools aren't doing it. By reading your child's work, you create an audience for the child: it is very very important for writers to recognize that they have a reader. The writing stands in place of the writer before the reader - the writer is not there to answer questions, so the writing must stand all on its own. Make your children realize that they are addressing an audience. Have the children read what they have written aloud. Look at your own writing, too. Ask yourself, "Does my writing make sense?" That is, does it make sense to other people?

The home is more important than the schools Read. Read anything. Writing is extremely difficult: make children realize that. Persuade children of the advantages of good writing.

Is it useful to rehearse some of the advantages? (Them I got without asking.)

The constant checking and reworking necessary to good writing demands the exercise of clear thinking, precision, attention to detail.

Bad writing causes confusion, ambiguity. Precision is needed, especially in legal matters archives, business documents, politics.

Writing is our one means of convincing by pure logic, because writing is dispassionate (it commands no gestures, voice changes, or shouting). Errors are leveling. When disinterested and uninterested are used interchangeably, for instance, a sharp distinction is broken down, and the language is thereby impoverished.

The shape of the language determines the shape of the history that is being written in it.

Certain errors stigmatize a writer socially.

The real world hasn't got time to read folderol.

Poor writing compromises your effect: errors make an audience refuse to accept you as an educated person, and so refuse to accept your engineering.

Graduate students cannot stand on their own feet if they need always to run for help with the expression of their research.

Students need to get government contracts, research grants, to sell ideas to municipalities.'

Verbal ability is a better indication to Admissions that a student is likely to succeed in college than is mathematical ability.

People do their thinking through words. Training in the use of words is training in thinking. A college devoted to clear thinking is perforce devoted to clear, accurate writing.

As I put down my pen, I feel my heart leap up. I was trained to teach English. And for 13 years now I have been irrelevant.

Professor Wira, physiologist: "This college cares enough to teach one language,free, to everyone in town. Why is computer BASIC more important than English?"

David Bradley, curmudgeon, reads aloud: "The need for building expansion may notbe necessary." And the student reacts: "Oh. Oh, but I didn't mean to say that."

Shelby Grantham is co-editor of classnotes and obituaries for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureES 21

January 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Article

ArticleThe Quirk Formula

January 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleThe Chuggers

January 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH '78 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1972

January 1977 By JOHN D. BURKE, DAVID J. FRIEND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

January 1977 By WALTER C. DODGE, THEODORE R. MINER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

January 1977 By GEORGE E. COGSWELL, EDWARD S. BROWN, JR.

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Feature

FeatureA winter of discontent, a day of perceiving differences

April 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

MARCH 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature'Far Out and Daring': Dartmouth Abroad

SEPTEMBER 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryConsortium

APRIL 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

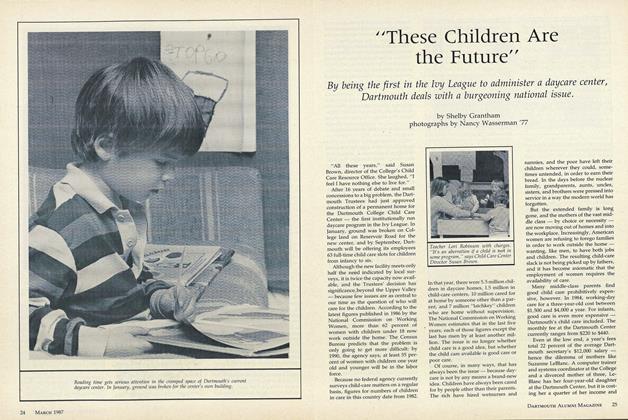

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe 1961 Alumni Awards

July 1961 -

Feature

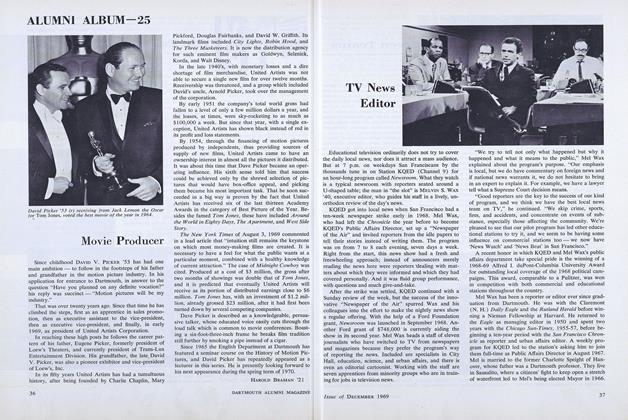

FeatureTV News Editor

DECEMBER 1969 -

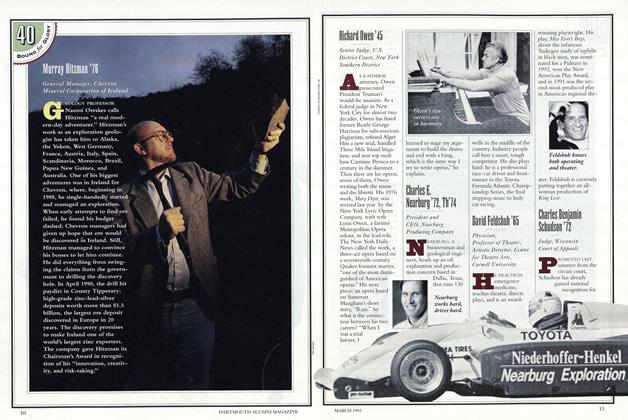

Cover Story

Cover StoryDavid Feldshuh '65

March 1993 -

Feature

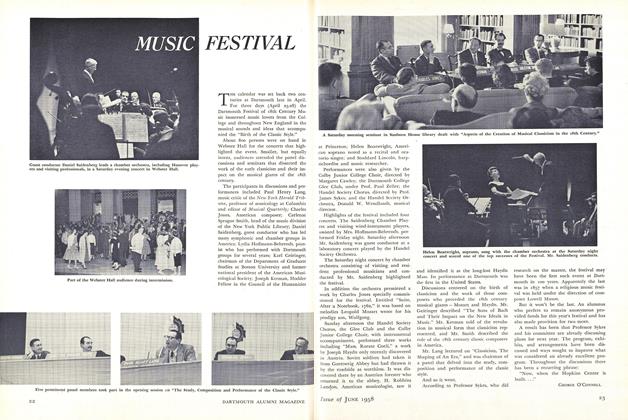

FeatureMUSIC FESTIVAL

June 1958 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureSCOPE: Off-Campus Options Made Easier

MAY 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

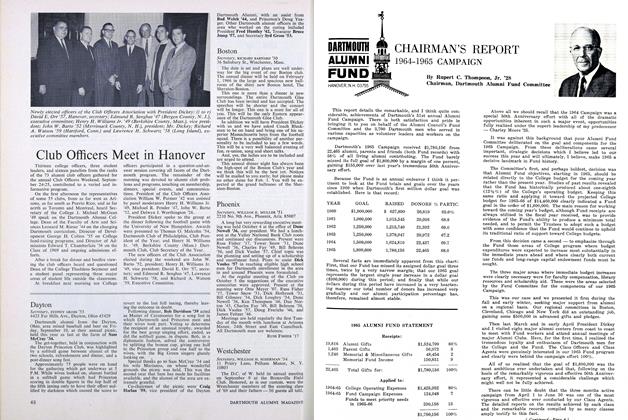

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

NOVEMBER 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28