TILLING his father's rock-studded field, James Marsh must have had little notion that he would one day set the intellectual world ablaze. But with his publication of Coleridge's Aids to Reflection many years later, in 1829, he did just that. This book, described by F. O. Matthieson as "the most immediate force behind American Transcendentalism," articulated the thoughts James Marsh had had as an undergraduate at Dartmouth.

There are widely divergent opinions about the exact date Transcendentalism came into being in America, but there is general agreement about the one institution most intimately connected with the religious movement: Harvard University. And rightly so, for not only was Harvard the intellectual hotbed of religious discussion with its controversial Divinity School, but many of the leading figures of Transcendentalism were harvard men. There is, however, little mention of the influence of a smaller institution directly connected with the early stages of American Transcendentalism: Dartmouth College. This influence, clearly reflected in the events surrounding the life of James Marsh, was expressed in several ways in the early 1800's: in the religious controversy which exacerbated a delicate posituation into the Dartmouth College Case; in the introduction of German philosophy into American academic circles; and in the academic milieu of a Dartmouth which produced several outstanding scholars. In each of these instances, James Marsh was immediately involved.

Marsh's beginnings were humble indeed. Although his grandfather had been prominent in Vermont's political and educational affairs, Marsh worked a meager plot of land along with his father in the rocky foothills of Hartford, Vermont. It looked as if young Marsh might never get beyond the New England Primer he studied in the local common school; he spent his first eighteen years working in the field, with the expectation of being a farmer, like his father. It had been decided, too, that James' older brother, not he, would attend college. But this plan was reversed for some reason and it was decided that James would go. His prospects thus broadened, James set off in 1812 for Randolph, Vermont, where he 1812 for Randolph, Vermont, where he spent the year under the tutelage of William Nutting, proctor of Randolph Academy. By the end of the year he had learned enough Latin, Greek, and mathematics to be admitted to the Class of 1817 at Dartmouth. In what was surely one of the major turning points of his short life, he struck out from his home in Hartford, crossed the nearby Connecticut River, and entered the serene wilderness of Dartmouth College. As Ruth White points out in her illuminating essay, "James Marsh: Educator," there was never any other place the youthful Marsh thought of attending: Dartmouth was a prestigious, well-established college; it was close to home; and his cousin .George Perkins Marsh, whose father was an eminent member of Dartmouth's Board of Trustees, was going to enter the College in three years.

During his undergraduate years, Marsh was a serious student who, like Francis Bacon, took all knowledge to be his realm. The subjects he was fond of - Latin, Greek, English literature, literary history and criticism - he read avidly. But he did not neglect mathematics and science, of which he was not so fond. Joseph Torrey, his biographer, claims that he was "patient and thorough, shrinking from nothing that was difficult or abstruse, but rather taking delight in whatever served to task his powers and rouse them to their utmost exertion."

A second major turning point in his life came in the spring of 1815 when the verdant Hanover plain bristled with religious controversy. The Reverend Roswell Shurtleff, Professor of Divinity, was in the process of his second massive campaign to convert Dartmouth students. James Marsh was moved. He recorded in his diary a fairly complete account of the conversion of one of his classmates, and ultimately decided that he too would commit his life to God. He had cast aside his old view of a God in Heaven and had come to the conclusion that within his own physical and spiritual being resided a divinity heretofore undiscovered. But with this epiphany also came the realization that his own life had been one quite apart from religion. He became depressed and dropped his academic pursuits for several weeks. Shortly thereafter he made a public declaration of his new-found faith in God and recommenced his studies with a new vigor and direction. The religious crisis which molded the transcendental temper did not mean the end of his intellectual endeavor at all. As his friend Torrey put it:

It rather stimulated him to greater exertion; his mind expanded with the more ennobling principle by which its energies were now directed; and instead of contracting his aims, and seeking to content himself with humble attainments in human science, he felt himself bound, more than ever, to cultivate, to the utmost possible extent and in every possible direction, the powers which God had given him.

Religious conversion, however, was not the only issue exercising Dartmouth men in 1815. By that time the College had become deeply involved in the Dartmouth College Case, during which, according to Lewis Feuer, "the first roots of American Transcendentalism . . . emerged as a philosophical response to the angry, impassioned controversy" which had begun some years before as a personal struggle between John Wheelock, Dartmouth's aristocratic second president, and the Board of Trustees.

The Supreme Court's decision in favor of the original Trustees established the validity of contract and assured independent colleges throughout the land that their integrity could not be impaired by state assemblies. But in addition, the Dartmouth College Case manifested the vehement outcry of the early American Transcendentalists; it demonstrated their vociferous rejection of an imposition thrust upon them from without; it represented their denial of the "traditional" philosophical tenets of the Scottish philosophers and Locke. Moreover, the state could not assail the sanctity of the individual.

During the long, grim years when the case was being fought in the courts, Feuer described the College as a "spirit without a body . . . without buildings, without libraries, without apparatus." But Dartmouth College survived. In fact, it survived remarkably well, for as Torrey, who was there as an undergraduate himself, recollected: "... within the bosom of the college, the strictness of discipline and regularity of studies never suffered any serious interruption. Some of the best scholars ever educated at Dartmouth went through the worst of these days."

Among those who endured, several were meeting weekly under the guidance of Shurtleff to discuss the events making headlines from the Upper Valley to New York City. This group included James Marsh; the brilliant Rufus Choate, Marsh's best friend; Joseph Torrey, Class of 1816, Marsh's biographer and a later President of the University of Vermont; and George Perkins Marsh, Class of 1820, Marsh's cousin. White described their meetings:

Together they read and discussed the pamphlets written about the struggle and the events as they happened. They met with other students and with faculty members, and they took up the cause of Dartmouth College as that of a struggle for freedom against tyranny.

Out of these weekly meetings grew an insatiable intellectual curiosity that was beginning to shape the life of James Marsh. Later he was to tell his own students about his literary club and how its members had become so proficient in their studies that their instructors excused them from class in order that they might pursue their work independently. The library which Marsh's literary club was assembling was small, however, and this limited the breadth and scope of their reading. Further study would have to wait.

This opportunity came soon for James Marsh, not at Andover Theological Seminary, which he entered in the fall of 1817, but back in Hanover a year later. Dartmouth had offered Choate, the valedictorian of the Class of 1819, a position as tutor. Choate remained in Hanover for one year, not to return to the College on the hill for a significant event until some 36 years later to deliver the eulogy for his idol, Daniel Webster. When James Marsh was also offered a tutorship, he was anxious to return to Hanover society, to the country he knew and loved so well, to the College which had opened so many doors to his mind. While at Andover, rarely attending classes because he felt they were a waste of time, Marsh had tried to form another literary group, but his efforts met with little success. But when he returned to Hanover in 1818, he established a new literary club in which he found great stimulation. In fact, these two years spent in Hanover (1818-1820) were among the happiest and most productive of his entire life. He had free time to pursue the studies he had dreamed of undertaking, including his survey of English literature, a re-reading of the Romantics, and a more extensive reading of literary history and criticism. He also found time for a less literary subject: Lucia Wheelock, a niece of Dartmouth's former president, John Wheelock. Their relationship, which was cultivated earlier when Marsh was an undergraduate, culminated in marriage in Hanover some years later, only to be marred by her early death after less than four years of married life.

The Hanover years matured James Marsh and convinced him that whether through literary clubs or introspection, the important thing was to be a thinking man. Returning to Andover for the second time in 1820, Marsh continued his independent research, taught himself the German language, and began a translation of Bellerman's Geography of theScriptures. It was at Andover that he met George Ticknor (Dartmouth 1807), a professor of ancient and modern languages at Harvard. Ticknor, who had returned from the German universities in 1816, conversed with Marsh about Kant and other German philosophers whose influence on the Transcendental movement was as profound as Coleridge's. At that time, it has been estimated, there were about six men in New England who knew both the language and the literature of Germany. Two of them were Dartmouth graduates Ticknor and Marsh. Their association was mutually rewarding and intellectually stimulating. Each holding the other in highest regard, they continued their correspondence well into Marsh's presidency at the University of Vermont, exchanging pamphlets and ideas, introducing to their students and their colleagues German ideas which were the backbone of Transcendentalism.

Marsh's studies at Andover were of incredibly broad scope, ranging far beyond the normal ecclesiastical curriculum of the day. As he pursued his religious studies, he remembered his successful days as tutor in Hanover where his informal classes, the forerunner of today's seminar, had been so popular, and he decided that he belonged in teaching and not the ministry. Thus, it was not surprising that upon graduation from Andover he should accept a teaching position and not a pulpit. His respect for Dr. Rice of Hampden-Sydney College and Seminary led him to join the faculty there, although he had considered taking a Greek tutorship at Harvard in 1823. Marsh was an instructor of language at Hampden-Sydney for two years until he assumed the presidency of the University of Vermont in 1826.

The inauguration address he delivered in Burlington on November 28, 1826, described as the first public utterance of American Transcendentalism, marked the beginning of a new era for the small Vermont college. Buildings were renovated, a new faculty was brought together, and the entire curriculum was revised. Philosophy was elevated to a new eminence to become the synthesizing nerve through which all else was ordered and perceived, and English literature was taught for the first time in any American college. Vermont thus became the place where the principles and ideals of the early Transcendental.movement were put into practice.

By 1829 the University was far more secure, financially and academically, than it had been three years earlier. On the president's desk lay the rough draft of the "Preliminary Essay" which was to accompany the first American edition of Coleridge's Aids to Reflection. Although Aids had first been published in England in 1825, it was virtually unknown in America until Marsh published it himself in Burlington in 1829. This one book, more than any other, was to lay the foundations of American Transcendentalism. In fact, as Ruth White points out, by the time the Transcendental Club met at George Ripley's home in Boston in 1836, not only were they all familiar with Marsh's introduction, but several knew him personally. What had appealed to the Transcendentalists so much about Marsh's "Preliminary Essay" was the fundamental distinction he made between reason and understanding. While the Lockean philosophy had used the words interchangeably, Marsh found a significant difference between them. Understanding, he felt, was the innate ability of the mind to comprehend and use what was sensually perceived; and reason was the ability to perceive and use a higher knowledge than that acquired through the senses. He also felt that the split between religion and philosophy in the Lockean philosophy had to be harmonized into a philosophical religion. The Transcendentalists thought so too.

The impact of Aids to Reflection was great. To the theological seminaries at Andover, Yale, and Harvard, Marsh's "Preliminary Essay" was heresy. In striking out against the widely accepted Lockean philosophy Marsh wrote:

The difficulties in which men find themselves involved by the received doctrines on these subjects, in their most anxious efforts to explain and defend the peculiar doctrines of spiritual religion, have led many to suspect that there must be some lurking error in the premises. It is not that these principles lead us to mysteries which we cannot comprehend; they are found, or believed at least by many, to involve us in absurdities which we can comprehend . . ."

During the next two years, reviews appeared in scholarly journals, many of them scoring both Marsh and Coleridge for heterodoxy. Some reviewers, however, were pleased with Marsh's work. Noah Porter spoke of the book as opening new avenues of inquiry and rendering the current theology "tolerant." Frederick Hedge, who was present at the first meeting of the Transcendental Club in Boston, praised it warmly and in the process used the word "transcendentalist" in the sense that it was understood by New England thinkers.

In 1830, the Reverend James Marsh became the Reverend Doctor James Marsh with Columbia's honorary doctorate. He continued his scholarly research, editing and translating German authors previously unknown to American scholars, and publishing, in 1830, Coleridge's The Friend, with a much shorter introduction than he had written for Aids to Reflection.

Having set the University of Vermont on a firmer foundation, Marsh stepped down from his office because of failing health and a desire to devote his energies to the profession he loved teaching. He was succeeded by the Reverend John Wheeler, who, like Torrey, was graduated from Dartmouth in 1816 and was attracted to the University of Vermont by Marsh. Dartmouth's voice in the University continued to be heard.

Unhappily, Marsh's later years were filled with sadness. In poor health himself, he watched helplessly as Laura, sister of his first wife, fell ill and died. He never recovered from this blow, weakening until tuberculosis finally consumed him in 1842.

Ironically, the Father of American Transcendentalism never really joined the ranks of the Transcendentalists. He was too far from Cambridge to meet with Emerson, Thoreau, and Ripley on any regular basis. And according to John Duffy, he was becoming interested in Hegel and may well have become a Hegelian had he lived longer.

It is unfortunate that James Marsh the man does not emerge successfully in Torrey's biography. But certain aspects of his personality do stand out. Obviously, he had a keen mind (John Dewey, a first-rate thinker himself, remarked that Marsh "never had any second-hand thoughts") and, obviously, he had charisma. Students flocked to his classes in psychology and quite literally became his disciples. But James Marsh was neither a good speaker nor a good administrator. He was most at home in the realms of thought.

Dartmouth's role in the early-Transcendental movement in America has never been as clear as James Marsh's. But fortunately for Transcendentalism, it had (to rework a line from Robert Frost) one James Marsh and the Dartmouth needed to produce him. THE AUTHOR of this article is Instructor in English at Champlain College, Burlington, Vermont.

James Marsh, Class of 1817

Marsh's letter to George Ticknor about a Greek tutorship at Harvard.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFaculty Votes Reduced Status for ROTC

March 1969 -

Feature

FeatureReaching Out from Hanover

March 1969 By Ron Talley '69 -

Feature

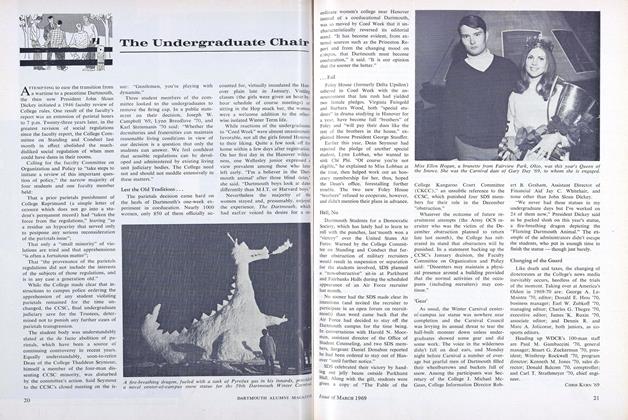

FeatureCOED WEEK: A Taste of the Future?

March 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1958

March 1969 By WALTER S. YUSEN, WILLIAM C. VAN LAW JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

March 1969 By THOMAS J. SWARTZ JR., HERMAN E. MULLER JR.

Features

-

Feature

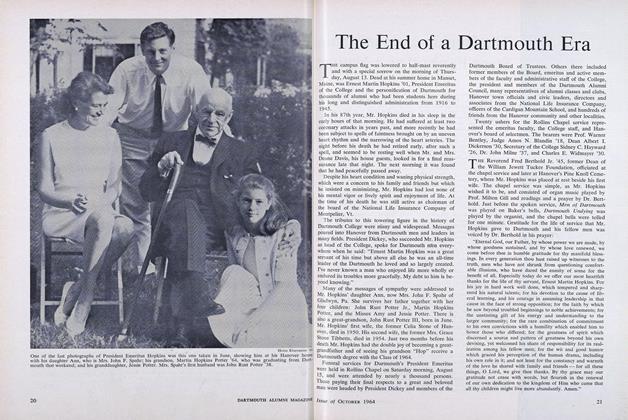

FeatureThe End of a Dartmouth Era

OCTOBER 1964 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAbandon All Hope

April 1981 -

Cover Story

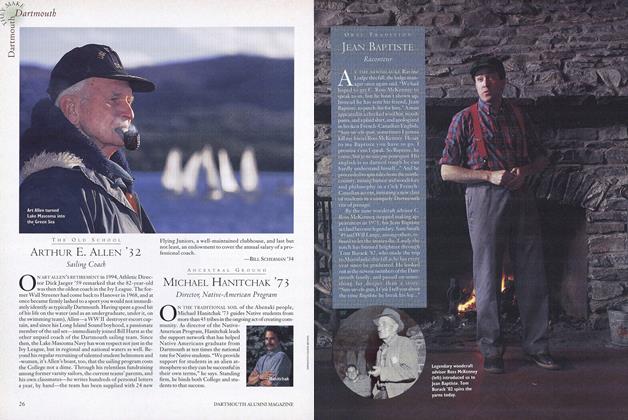

Cover StoryJean Baptiste

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

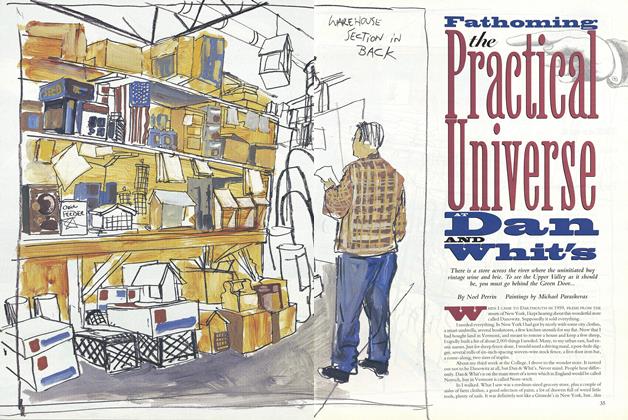

FeatureFathoming the Practical Universe Dan and Whit's

April 1995 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureThe First 25 Years of the Dartmouth Bequest and Estate planning Program

September 1975 By Robert L. Kaiser '39 and Frank A. Logan '52 -

Feature

FeatureMt. Washington Pathfinder

January 1956 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29